Bound to a limited visual lexicon for over a century, tattooing has sprung free in the new millennium, liberated by artists who combine fresh concepts, holistic design, and masterful technique in thrillingly original styles. They draw inspiration from historical genres spanning Pointillism, Expressionism, Pop Art, and Photorealism; from an array of timeless ethnographic traditions; from illustration and graphic design, comics and street art; from regional folk arts; and from the Japanese style that has informed Western tattooing for the past century. The artists presented in “Body Electric” confirm that tattooing has turned a corner into an entirely new realm of artistic possibility. They are auteurs of body art.

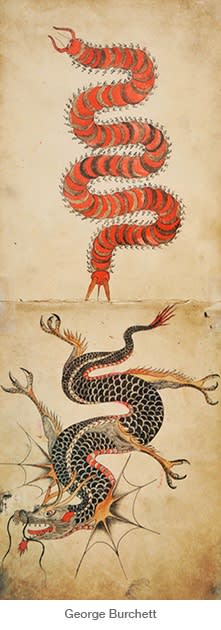

But they stand on a continuum of innovation. While most tattooists of the late 19th and early to mid-20th century were essentially untrained copyists, duplicating popular designs from “flash” sheets posted on shop walls for customers to choose from, some, like the celebrated British society tattooist George Burchett, were dedicated artists. Indeed, the distinction between artist and journeyman was established early on. In Memoirs of a Tattooist, Burchett noted that his friend Sutherland MacDonald, a pioneer of the 1890s, coined the word “tattooist” as a term of, well, art: “Tattoo artists had always called themselves tattooers. But MacDonald insisted that an artist is a tattoo-ist, and only dabblers and low alley-fellows should be described as tattoo-ers.”

In 1889, Burchett witnessed the magnificence of Japanese tattooing on a trip to Tokyo where he met Hori Chyo, the master whose clients included European royals and aristocrats. Noting the artist’s “delicacy of line, the precise detail, and above all, the glowing colors and subtle shading,” Burchett concluded that “[W]estern tattooists, however skilled and gifted, were only imitators of an art which had been cultivated in Japan for 2000 years.”

For a long time, that held true, but the transformative moment for Western artists came less from copying Japanese work than from applying its principles to a homegrown lexicon. Honolulu artist “Sailor Jerry” (Norman Keith) Collins led the way in the 1960s, even as he inked a steady stream of sailors. “I want to be an original…” he wrote, “…not a half-assed [imitator] that has to trace his designs before I can work.” Departing from the Old School practice of applying boldly executed tattoos, helter skelter, across the body, he tackled large and complex compositions, tested new pigments, and mixed gray tones for shading that produced the depth and contrast of Japanese work. He—and a handful of tattoo aesthetes like him–brought technical refinement and compositional sophistication to classic iconography.

Collins’ protégé, Ed Hardy, revolutionized the imagery itself. Hardy came to tattooing in 1966 with a degree in art, galvanized after seeing full body tattoos in the book Irezumi: Japanese Tattooing by Ichirō Morita and Donald Richie. The encounter was life-changing. He subsequently declined a full graduate scholarship to Yale in order to pursue tattooing—and changed the course of Western tattoo history. “I knew that tattoos didn’t just have to be an eagle and an anchor,” Hardy wrote in his memoir, Wear Your Dreams. “I understood that it was spectacularly transgressive. Nobody was doing it […] Yet it seemed to me it could be done so that it was a challenge as a visual art form.”

Through his experimental designs, his publishing ventures (the only sustained, serious scholarship that has ever appeared in tattoo magazines), his founding of the first appointment-only shop, and his embrace of hippie, punk, and Chicano styles, Hardy—and a group of sympathetic visionaries–initiated a tattoo renaissance that’s been advancing steadily since the ‘70s. It flourished in a variety of new industry hothouses: in 1976, the first annual convention brought artists together to ply their trade and share ideas (there are now hundreds, internationally, each year); in the ‘80s, tattoo fan magazines emerged to show the work of notable artists, (dozens have followed); in recent decades, the internet has streamlined the sharing (and stealing) of new work on a global scale; today, curated collections appear on Instagram and Pinterest.

Since the 1990s, waves of innovative tattoo trends have propelled this art far beyond its Euro-American folk roots, tapping into–and in the best cases reinterpreting—non-Western traditions like tribal tattoo of the Pacific, or replicating highly specific looks, like the “biomechanical” style culled from the techno-dystopias dreamed up by the Swiss artist H.R. Giger. But for all the talent on display in tattoo shops internationally, and despite the growing number of tattooists emerging from art schools, few artists transcend—rather than remix—familiar tropes. For a medium devoted to individual expression, tattooing has not produced many masters whose work is truly sui generis. Until now.

“Body Electric” introduces a new generation of conceptual trailblazers. The visual art featured here reflects their tattoo sensibility—the next best thing to showcasing the living canvases that bear their designs.

They hail from around the globe: In Lucerne, for example, Jacqueline Spoerle uses Swiss folk motifs in lyrical silhouettes perfectly suited to tattoo’s inherently graphical nature.

In Los Angeles, Chuey Quintanar takes fine line black and grey portraiture to a new level of grace and power. New Yorker Duke Riley’s maritime narratives betray a blush of nostalgia through strong line work and meticulous cross-hatching.

In Argentina, Nazareno Tubaro blends tribal, Op Art, and geometric patterns in flowing compositions that embrace and complement human musculature.

And in Athens, Georgia, David Hale, a relative newcomer, folds the curvilinear lines of Haida art into his folk-inflected nature drawings.

The exhibition includes a selection of flash art spanning the late 19th to mid-20th century. These pieces, many by titans of the trade–George Burchett and Sailor Jerry Collins among them–represent the keystone style of Western tattoo tradition and the semiotic conventions that define it, from hearts and anchors to pinups and crucifixes. Conveying both the charms and limits of these pioneers, they offer a baseline for understanding the evolution of tattooing over the course of the past century.

Though some of the contemporary artworks shown here could be considered flash in the sense that they are actual designs, none are intended to be templates. These artists, like most top notch tattooists today, do custom work. Some have art degrees; some served apprenticeships; others are self-taught. Some work in fashionable shops like Saved in New York and Into You in London; others run private studios. Some enjoy dual careers as visual artists. (And some sensational tattooists whose sensibilities simply don’t translate to two dimensions could not be included). By bringing visual sophistication and art historical engagement to their work, the new auteurs have freed tattooing from the subcultural parameters that both sustained and restricted it for over a century. They’ve opened the door to an exhilarating new pluralism, reimagining this art for the 21st century.

Margot Mifflin is the author of Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo (PowerHouse Books, 2013). She’s a professor at Lehman College /CUNY and co-directs the arts reporting program at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism.