In the self-taught artist Dan Miller’s big, new abstract drawings, richly textured compositions energize the space

“Dan Miller: Large Drawings,” an exhibition to benefit Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland, California, on view at Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York, June 17-August 20, 2010

Photo-portrait of the artist Dan Miller by Cheryl Dunn, courtesy of Creative Growth Art Center

Around the world, even as photography-based creations and mixed-media installations remain highly popular formats for many different kinds of contemporary art-makers, abstract painting continues to hold its own as one of modern art’s most powerful and multifaceted modes of expression. Nearly a century after the French painter Claude Monet created his monumental depictions of water lilies—those late-Impressionist, form-distilling essays in light and color that anticipated the expressionistic, gestural abstraction of a later era—artists in many parts of the world continue to embrace and explore abstract art’s potent language of ambiguous meaning and often open-ended emotion.

How or why an artist arrives at and takes up an abstract approach to art-making—reasons for such a decision, whether it’s a conscious choice or not, can be as varied as the evolution of any artist’s working methods and ideas. Based in northern California, where he has been a regular participant for nearly 20 years in the art-therapy program at Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, the self-taught artist Dan Miller has developed one of most distinctive styles of any abstract artist, academically trained or untrained, who is working today.

Miller, who was born in 1961 and has a severe case of autism, also suffers from a seizure disorder; he speaks very little and uses only simple words. Through art-making, though, he has given expression to a creative impulse that feels at once urgent and compelling, and just as focused in some ways as the abstract images it yields remain mysterious and strange.

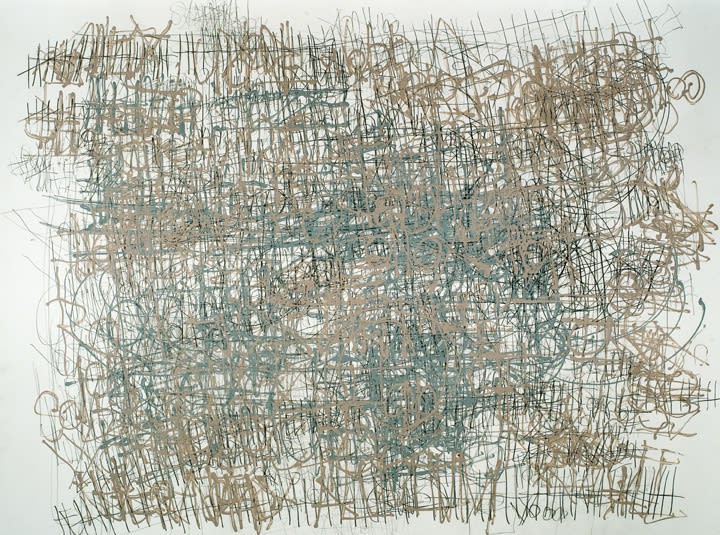

Untitled (Large Works), 2010; mixed media on paper; 40 ins. x 60 ins.

When Miller first started making drawings years ago, recalls Tom di Maria, Creative Growth’s director, he made simple, figurative pictures of such subjects as light bulbs, rabbits or human faces. Usually he wrote words right onto his paper, incorporating them into his images.

Over time, his compositions became more complex, his figurative subject matter disappeared, and the artist began to draw letters or words alone. “His letter forms became abstract, dense and elegant,” di Maria says. “He made some with fine-pointed markers and pencils.”

Matthew Higgs, the director of White Columns in New York, notes that Miller’s mature, best-known drawings “take the form of accumulations of individual words, alphabets and numerical sequences.”

Miller’s abstract images are made up of letters, words and numbers drawn on top of each other over and over again

Higgs, whose alternative-space, contemporary-art center presented a solo exhibition of Miller’s drawings on paper in 2007, points out that the words or brief texts that are the thematic raw material of the artist’s works “often have strong biographical references; they might acknowledge specific Bay Area locales and aspects of Dan’s immediate day-to-day life or family history.”

Untitled (Large Works), 2010; mixed media on paper; 40 ins. x 60 ins.

As Miller repeatedly superimposes words, numbers or phrases on top of each other, building up dense forms that seem to spread out organically in an image’s pictorial space, these elements “start to merge,” Higgs notes, “creating all-over fields of partially obscured and often illegible texts.”

In 2008, several of Miller’s works on paper were included in “Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing,” a large and diverse exhibition that was organized by and presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; it featured pieces made by both academically trained and self-taught artists. Later, the museum acquired some of Miller’s drawings for its permanent collection, a development some observers in the field of self-taught artists’ art regarded as a noteworthy vindication of the aesthetic quality and critical significance of the work of a decidedly outside-the-mainstream autodidact.

In a mysterious, compelling way, Miller’s works give visible expression to “the cacophony that is daily life”

An exhibition of Miller’s newest drawings on paper will open at Ricco/Maresca on June 17, 2010. It will showcase the artist’s most recent experiments with various media, including pencil and paint, on some of the largest sheets of paper he has ever used (some measure roughly three by four feet in size).

Miller at work; photo by Leon Borensztein, courtesy of Creative Growth Art Center

Di Maria explains that, to make some of these large drawings, whose mostly monochromatic palettes include some deep blues and dark reds, Miller applied paint to his paper’s surface, then used the stick end of his brush to incise lines in the paint. “Dan seems to like using large sheets of paper and having more space in which to spread out,” di Maria says. “His work continues to evolve.”

More recently, Miller also has been using an old typewriter to type letters and words on sheets of paper. In his typewriter-produced drawings, the artist often types words and letters over each other or in patches in an apparent effort to imitate the technique he more commonly employs using pencils or pens. “Sometimes he draws on top of the typed words, too,” di Maria says.

Untitled (Large Works), 2010, mixed media on paper, 40 ins. x 60 ins.

With their thickets of wiry lines interspersed with patches of color or clusters of knotty, broad strokes, Miller’s untitled new works offer an illusion of layered space sinking deeply into each drawing’s two-dimensional surface.

They are rich in affinities to some of the most emblematic works of classic abstract art—think, for example, of the painter Philip Guston’s canvases from the early 1950s, with their floating passages of color made up of cross-hatched strokes, or of the dense passages of swirling, impetuous lines that turn up in many of Cy Twombly’s heroically scaled drawings and paintings.

Matthew Higgs of White Columns notes that Miller, with his “dynamic, yet highly disciplined drawing and mark-making, intuitively combines both conceptual and expressive approaches to create a truly idiosyncratic, hybrid form.” Higgs suggests that Miller’s works can be seen as giving visible expression to “the cacophony that is daily life” as they “articulate something of the relentless ebb and flow of thoughts, ideas and emotions that are common to us all.”