Renaldo Kuher invented the fantasy world of Rocaterrania as a teenager and inhabited it all of his adult life, which stretched from the mid ’40s until his death in 2013. By a bizarre confluence of its creator’s fixation on pin-ups, Fritz Lang, spy novels, and late Bohemian, Hapsburg, and Prussian fashion/architecture, his dystopian land of make-believe, situated on the border between New York State and Canada, turned out to be a demesne of steam-punk aesthetics and rockabilly swingers. By virtue of its edgy sexual tension and questionable political regimes, Rocaterrania was much more entertaining than the dull rehash of Cimmeria (Conan the Barbarian’s homeland) that is Westeros (Game of Thrones). In its farfetched plots and absurd cast of dastardly villains and dreamy heroines and heros, Rocaterrania is more akin to the philosophically engaging fairylands of Narnia and Oz, than to those aforementioned lands pretending to have some semblance of politics and reality. Kuhler worked professionally as a scientific illustrator and his drawings in that capacity are finished to an extraordinary level of precision and crispness. His depictions of Rocaterrania are by contrast wonderfully loose, yet still maintain the intensely patterned inking techniques of that technical genre of drawing: cross-hatching, stippling, and details that imitate etching and aquatint printing. The base on which they are drawn is often sheets of lined paper from notebooks, which only adds to the mad-scientist quality of Kuhler’s creative process.

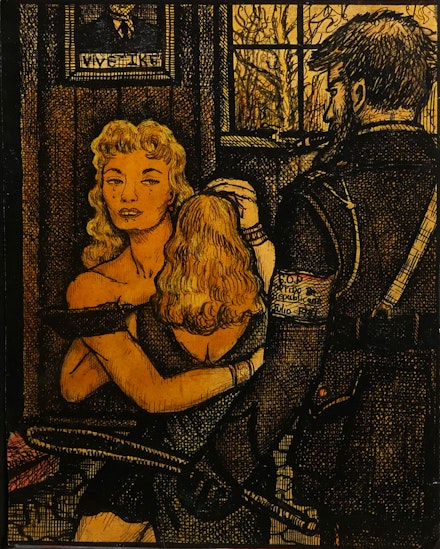

Kuhler’s basic themes and details are for the most part predictable and arise from Cold War paranoia—the characters speak a language of Russian, German, and Yiddish, written in a combination of Cyrillic, Hebrew, and German gothic script. There is a pocket-sized notebook of phrases in Rocaterranian, Light brown calligraphy notebook (1970s). The pop-culture influences are juvenile: the female characters in his illustrations are thinly veiled references to mainstream movie ingénues or bombshells with derivative names like Judith Gartland. The politics and history of Kuhler’s Lilliputian kingdom are carefully narrated, with all the plot twists and turns of a Viennese Operetta; one can choose to become engrossed in the artist’s soap opera-like meanderings of revolutions, affairs, and abductions by reading the monograph on the artist or watching the documentary film, both created by Brett Ingram, or simply observe the drawings and soak up the gritty film-still drama at face value. Viscountess Florence Ostenwelt holding Anne Maria de Rochelle, sickly daughter of Cesar, held Captive by Captain Hinds (1953), is just such a composition in which a spotlighted and resolute heroine, stage center, clasps an inconsolable woman to her bosom while a looming uniformed bearded officer, with a political armband, observes from the too-close-for-comfort foreground. It is the camp of the scene—supposedly flustered captives with perfect hair, makeup and lighting, and the underlying sexual chemistry between the villain and his prey that make these images deliciously alluring.

Along those lines, some of Kuhler’s imagery can seem troubling: There are dark bearded shady figures who are clearly depictions of Jews, as well as other swarthy characters with warty noses and demonic glints in their eyes, conspiratorially gathered around tables in dark rooms (these images are in the monograph, not on the walls, but deserve a mention). On closer inspection, and akin to fellow caricaturist R. Crumb—who happily offends all with his grotesques—this cartoon style seems mostly to arise from the fact that Kuhler, in his own mind, inhabited a threatening and depraved world in general. The male figures exude a fearful imperial authority comingled with ugliness, while almost all the women fall into a Betty Page/Marilyn Monroe stereotype. The depictions of Rocaterrania, with few exceptions, emerge from a film-noire/ghost-story comic vernacular. There are carefully wrought views of the capital city of El Dorado, as in Casa Victoria (1958), Schwartz Opera House Reconstruction (1953), and The Great Wepka sewer plant outside Ciudad Eldorado (1965)—the buildings are festooned with sharp forbidding turrets and prickly evergreens line the streets and distant vistas. Most of the avenues and alleys of the cityscapes could be plucked from the winding thoroughfares of postwar Vienna à la Carol Reed’s The Third Man. It is no surprise then that there are also scenes of secret police raids and candle-lit insurrectionist gatherings.

The artist is not extolling a law-and-order or racially pure state, quite the opposite. He has an ambivalent affection for the world of his creation, and acknowledges its flaws: three drawings are particularly effective in exhibiting the dangers of rejecting democracy, and also directly reference the dangers of National Socialism: Gorghendi Kahn proclaims martial law (Janissary band marching) (1957), Labor service camp in White New Serbia (1959), and Lights from Felsenbad Stadium visible from RR tracks outside town (1959). Lights from Felsenbad Stadium mimics Speer's Cathedral of Light created for the Nuremburg Rallies of the 1930s. The initial wonder of the effects of the beams of light projecting into the skies is quickly replaced with a sense of horror, and the tortured bent telegraph pole and writhing leafless tree in the foreground highlight this sinking feeling.

Kuhler's most original contribution is "neutant"; a genderless/genderfluid inhabitant of Rocaterrania. The being is named Peekle Hannaford, and perhaps is a semi-autobiographical figure, as they dress much like their creator, who wore a custom-made uniform of shorts and a vest every day. The character appears in two works on paper in the show, Peekle Facing the Universe (2003) and Peekle Variation (1999): both images capturing this being in a tense stance, arms half raised and legs spaced apart like a wrestler preparing to engage an adversary. On Peekle’s elfin face is a half-sneer. Peekle also is present as an undated life-size sculpture creepily made from a modified mannequin with paper and plaster appliqués highlighting their androgynous qualities. This odd, anxious being, a stand-in for the author, raises the sobering question of whether Kuhler found the social acceptance in Rocaterrania that he was denied in his banal reality, or whether he was just an observer there, as well.