In the field of outsider art, remarkable discoveries have sometimes been made in dusty attics, boxes tucked away in garages, or ready-to-be-hauled-away dumpsters. Shortly before the reclusive, solitary Henry Darger died in 1973, his voluminous life’s work — more than 300 drawings and some 15,000 typewritten pages of his epic narrative, In the Realms of the Unreal — were discovered in the small rooms he had occupied for decades in a modest Chicago boarding house.

Generally speaking, admirers of outsider art tend to like a compelling biography to go with the uncovering of an unusual body of hitherto unknown work. Now, with the publication of The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler, by Brett Ingram (Blast Books), a first-ever account of the life and career of an autodidact who died in North Carolina in 2013, at the age of 81, fans of this kind of art may become familiar with a distinctive oeuvre that is as cohesive as it is ambitious, and with the intriguing eccentricities of the talented draftsman and storyteller who concocted it.

Ronald Otto Louis Kuhler was born in 1931 in Teaneck, New Jersey; his mother, Simmone Gillet Kuhler, whom he would grow to detest, came from Belgium; his father, Otto Kuhler, a designer of streamlined trains and an amateur painter, had emigrated to the United States from Germany. When Ronald was born, the couple already had a first child, the boy’s older sister. During the 1930s and 1940s, Otto Kuhler’s busy career kept him away from home, leaving the children at the mercy of their abusive mother. In the late 1930s, the family moved to Rockland County, north of New York City, a setting young Ronald seemed to like, but his parents packed him off to boarding school, where, as a shy and miserable boy who routinely wet his bed, he was painfully teased by his fellow students.

Such bullying continued right up until the late 1940s, when Otto Kuhler ended his career as an industrial designer, purchased a ranch in Colorado, and moved his family there. Feeling more isolated than ever in such a remote place, his son began keeping illustrated and typewritten journals detailing his daily experiences. “I felt more dead than alive and I will not mention the horrors of it,” he wrote in one entry. “What do I do here at the KZ Ranch?” he asked himself in another.

The teenager’s proficiency for drawing was evident in his pictures of cars, buildings, and other features of his surroundings. Before long, Ronald — it would still be several years before he would legally change his name to the more pleasant-sounding “Renaldo” — applied his considerable talent and powerful imagination to devising a great escape from the unhappy family life and dispiriting circumstances in which he found himself. Through his drawings, he began giving visible form to “Rocaterrania,” an imaginary country inspired partly by the Rockland County ambiance he had left behind.

Situated in upstate New York, near the border with Canada, it was a place whose made-up history, social system, and culture were also influenced by Kuhler’s interest in and knowledge of Victorian-era styles in general and his fascination with Germanic and 19th-century Eastern European lands. Over time, he even developed “Rocaterranski,” a unique language for his secret place in the imagination, complete with its own alphabet.

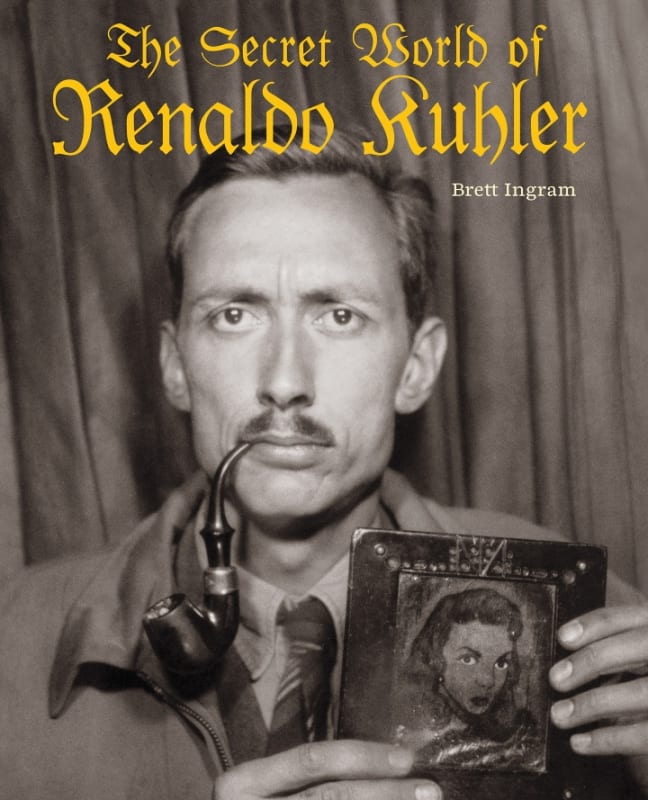

Tall and skinny, with a little moustache, Kuhler later stood out at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he smoked a pipe and favored three-piece suits, while his all-American peers wore their letter sweaters and preppy duds. Graduating with an undergraduate degree in history, he landed a job as a curator in that field at a museum in Spokane, Washington, where he worked for a few years and changed his name to “Renaldo Gillet Kuhler.” After returning to Colorado for a two-year program in museum studies, the odd fellow who drew himself pictures of an imaginary girlfriend moved to Raleigh to take up a new position as a scientific illustrator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. He would remain there until his death.

Today, Brett Ingram, The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler’s author, teaches filmmaking in the media studies department at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro. It was thanks to two chance encounters with Kuhler, he recalls in his new book, that he came to know the “flamboyant giant” who later became his friend and, ultimately, entrusted Ingram with the preservation of his artistic legacy.

Ingram first spotted Kuhler during a ride on a public bus in Raleigh in 1994. The elderly artist was more than six feet tall, he writes in the book, “with a bushy white beard and ponytail.” He wore “a custom-tailored uniform of indeterminate origin: a sleeveless, Kelly green suit jacket with wide, black, notched lapels, epaulets, and brass buttons, a matching suit vest, yellow flannel dress shirt, a fleur-de-lis Boy Scout neckerchief, and tight-fitting, knee-length shorts.” Although other passengers looked away, Ingram watched and listened as Kuhler declaimed about the virtues of public transportation. He writes that he at first found the old man to be “[j]ust another crazy person talking to himself,” but that the more he paid attention to his rant, the more he “noticed the good sense he made.”

Two years later, as Ingram was starting a media-development job at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, he was surprised to meet Kuhler there in person when his new boss introduced him to other employees; the artist’s workspace was tucked away in an annex building “filled with taxidermy, mammal skeletons, and jars of preserved specimens.” Ingram would later learn that Kuhler was completely self-taught as a scientific illustrator and “attributed his draftsmanship to his ability to see the world in detail.”

As skillfully rendered as the pictures on display around his worktable were — Kuhler drew snakes, birds, fish, and bone structures — it was the his precise, almost “obsessive” depictions “of androgynous humanoids in form-fitting uniforms” similar to the garments the artist wore himself that caught Ingram’s eye. Those images were labeled with what appeared to be the names of their subjects — “Eutie,” “Beulis,” and “Peekle” (all characters, it turned out, from Rocaterrania). Along with neatly hand-lettered bus schedules and lists of telephone numbers, such drawings, Ingram writes, “clearly [had] originated outside the purview of Renaldo’s job description.”

Ingram recalls how, over time, he befriended his new work colleague, who eventually invited him to visit his home. There, he showed him the uniforms he meticulously designed and arranged for a local tailor to construct for him, as well as drawings, notebooks, sketches, and hand-made objects — pipes, jars, badges, neckerchief holders — made of glued-and-sculpted cardboard that collectively represented his imaginary country. In his mock-lederhosen ensemble, puffing one of his elaborate, homemade pipes, Kuhler went out drinking with Ingram, looking every bit the incarnation of one of his Rocaterranian characters. (“You have beautiful teeth,” the artist would say during such outings to a woman he found attractive, not as a pick-up line but as a sincere compliment.)

As their friendship developed, Kuhler permitted Ingram to film him at his home and around town; Ingram used the footage he amassed to produce Rocaterrania, a documentary about the artist’s life and the evolution of his imaginary country, which was released in 2009. (The film will be screened tonight at Anthology Film Archives.) Later, after the artist’s death, Ingram inherited his large body of work and spent years organizing and carefully archiving it.

Perhaps even more straightforwardly than his movie, Ingram’s new book lays out the story lines of the different aspects of Rocaterrania that Kuhler developed over a period of some six decades. Blast Books’ founder and publisher, Laura Lindgren, noted during a recent interview at her Manhattan office that the new book “constitutes the complete telling of Renaldo Kuhler’s narrative for the first time.”

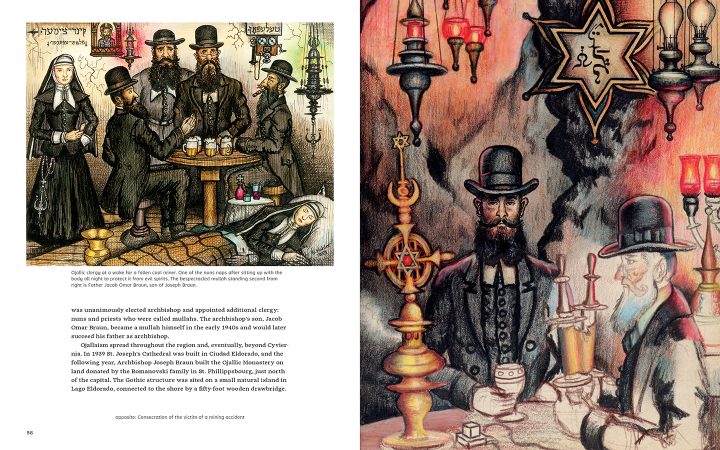

When I met Ingram at his home in Greensboro several months ago, he told me that he felt lucky that he was able to ask the artist many questions about Rocaterrania before he died. “Renaldo had it all in his head but he never wrote it all down,” Ingram explained. Thus, the new book provides a family tree and an accounting of the members of the imaginary country’s first emperor, Philippe Romanovski, a descendant of Russian nobility, and his offspring, as well as descriptions of its political revolutions, its multi-tiered society (in which Peekle and his pals are “neutants,” humanoids that are neither male or female), its ethnic groups, and its religions (like “Ojallaism,” which is rooted in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam).

Ingram, channeling Kuhler, also describes Rocaterrania’s social customs and scientific advances (one of its farms was “the first to use human waste as a crop fertilizer”), and summarizes, with some of the most striking of any of Kuhler’s full-color drawings, the story of a Rocaterranian film, supposedly produced in 1956, about the voyage of the nation’s astronauts to the Moon. “[T]he people need an escape once in a while,” a confidante of Rocaterrania’s president tells the little country’s leader in what is, in effect, the proposing of a fantasy within a fantasy. A reader can imagine Kuhler relishing his imagination’s rich turns.

The complexities of Henry Darger’s inventively illustrated, good-versus-evil magnum opus, with its legions of naked, Victorian little girls with penises in combat against monsters, armies, and hangmen, or those found in the work of the Swiss art brut legend Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930), whose alter ego, “Saint Adolf,” creates an entire universe within a 45-volume grand narrative filled with texts, musical scores, and elaborate images, might seem edgier or more sophisticated than the multifaceted but comparatively familiar storybook character of Kuhler’s big production. Still, as Ingram’s book suggests, Kuhler brought something of a polymath’s resources, along with effusive enthusiasm, to his creation of Rocaterrania in all its detail.

Lindgren, who worked closely with Ingram over several years to shape the new book (as well as design it, as she does all of her company’s titles), observed, “A lot of it is just simply delightful, as was Renaldo himself.” She was referring to the time she met the artist in person during his appearance in a group exhibition at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore in 2009. “He was sitting at his drawing table, which they had brought from his home in North Carolina, and his drawings were on display,” she said. “It was weird to have a human being on display, too, but he was so sweet. He looked at my male friend who had mutton-chop sideburns and was wearing a three-piece suit and said, approvingly, ‘The 19th century!’ He saw another long-haired friend of mine and said, ‘Schubertian!’”

Ingram’s book points out that Kuhler “drank a lot, smoked a lot, [and] talked a lot […] to anyone within earshot,” and that he “possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of history, architecture, and movies.” In addition, he was deeply knowledgeable about religions and languages, and “loved bathtubs, gaslights, long legs, ice cream and horses’ ears.”

After reading and considering Ingram’s recollections about the artist, certain questions inevitably emerge, especially: Like Darger, how much, if any, personal experience with sex did the artist have in his lifetime, and to what extent did his knowledge or understanding of human sexuality inform — or not — the erotic current that pulses through some of his art? As far as anyone knows, he was never diagnosed as autistic or mentally ill, but his behavior was of the kind that those around him would have described as “strange.” Still, he made his way through life and the world he knew on his own terms, and in his own way, he triumphed.

In Ingram’s book, old photos of Kuhler as a child show a youngster standing uncomfortably next to his mother, detached and awkward, with big eyes gazing somewhere a million miles away.

“The ability to fantasize is the ability to survive,” he once stated. As this book honoring the power of his imagination suggests, this discovery, for an artist and his audience, may be one of the most meaningful of all.