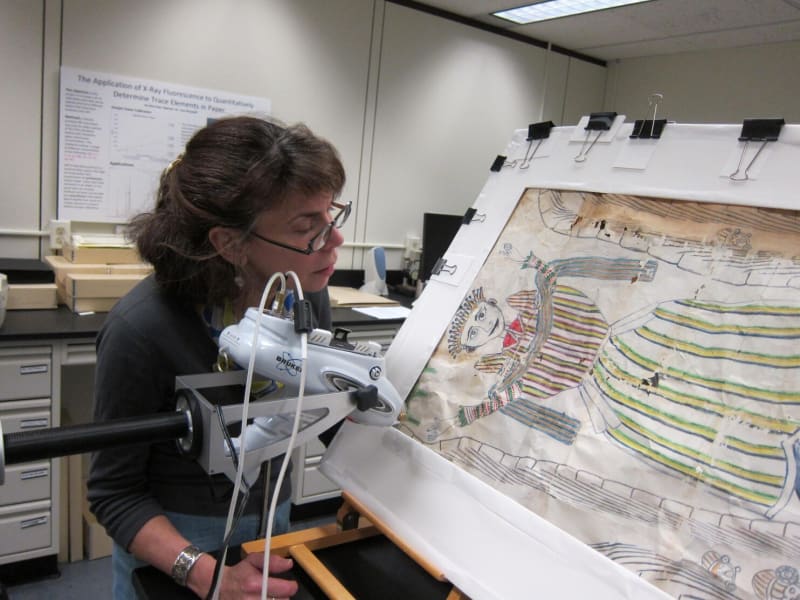

Lynn Brostoff of the Library of Congress Research and Testing Division analyzes artwork by Martin Ramirez. (Library of Congress)

About halfway down the geological layers of paper inside a box of archival materials, Tracey Barton came across a rolled-up, slightly crushed tube of paper which intrigued her. It was September 2009, and the 31-year veteran of the Library of Congress was sorting through old pamphlets and letters that once belonged to the legendary modernist design couple Charles and Ray Eames.

She unrolled the brittle and crumbling drawing just enough to discover an image of a woman rendered in what looked like a Mexican folk style. When she flipped it over, the mystery deepened: It was drawn on a crazy-quilt assemblage of old letters, envelopes and other scraps of paper, including a solicitation for nude photographs.

“When I saw all the junk mail, I thought I was looking at a piece of outsider art,” she says. And she was.

On Thursday, the Library of Congress will unveil the drawing, a lost Madonna by a Mexican artist who spent more than 30 years of his life institutionalized, much of it at Dewitt State Hospital in Auburn.

The drawing has been carefully preserved, patched and minimally retouched where insects ate away at the paper. It is a charming and energetic picture showing an angelic figure, with an androgynous face and a radiant crown, standing on a luminous blue globe. Surrounding her, and rendered in a different perspective, are two canyons filled with what seem to be automobiles, driving from a landscape of green trees toward the bottom of the vertical landscape, perhaps south, to Mexico.

But the arrival of this newly discovered work by Ramírez is exciting because in many ways it is utterly conventional. Although created by a man who fell through the cracks of society, who spent decades labeled as a schizophrenic, living in degrading conditions and working with matchsticks dipped in ink, Ramírez’s Madonna has been received into the loving arms of the academic and professional art establishment. It has been meticulously repaired, studied and dated. Its materials have been analyzed and its formal qualities put into the context of Ramírez’s other work. And even though one could put a price on it — his work has sold for six-figure sums in recent years — its primary contribution is a small but essential nugget of knowledge about a man who was once nameless, voiceless and forgotten.

That process began with Barton, whose experience as a senior archives technician made her alert to the telltale signs of what makes a piece of paper interesting. It continued about a year later, when she discovered a letter to Charles Eames from a prominent Sacramento art dealer who organized the first exhibition of Ramírez’s work. The April 1952 correspondence mentioned the gift of some “schizophrenic drawings,” which helped confirm that it was a work of Ramírez’s and establish that it was created some time before the letter was sent.

“A lot of his early work doesn’t survive,” says Brooke Davis Anderson, who has studied Ramírez’s life and oeuvre and is executive director of Prospect New Orleans, a contemporary art biennial show.

Ramírez left Mexico in 1925 to find work in the United States. By 1931, he had been institutionalized. At first deemed a manic depressive, he also developed tuberculosis, and although he tried to escape several times over the years, he would never leave the public hospital system, or see his family again. He died in 1963.

Ramírez scholars now believe that the former farmworker, who spoke little or no English, may have found the hospital a safer bet than life on the streets during the worst economic downturn in U.S. history. They also doubt, but can’t disprove, the later diagnosis of schizophrenia.

From the library’s Manuscript Division processing area, the drawing went for preservation, and senior paper conservator Susan Peckham spent six months stabilizing and repairing it. For years, Ramírez lacked proper drawing paper, so he made do with what he had. He also liked to work on a large scale — the new Madonna is more than two-by-three feet — which meant fitting together 22 pieces of whatever paper he could find.

“He chewed bread, mashed potatoes and/or oatmeal to stick the paper together,” says Peckham, which made the drawing delicious to bugs and extremely fragile. Peckham points to what she calls her “eBay Box,” a collection of vintage inks and felt-tip markers (small bottles of Parker “Quink” and Flo-Master pens) she found online, and experimented with to fill in missing parts of the original drawing.

Parallel to the restoration process, there was a legal journey. Because Ramírez was adjudicated “insane” in California, state law said his property couldn’t be sold off or taken from him, which meant his heirs had a legal claim on the drawing. In the catalogue to a major 2007 exhibition of Ramírez’s work at New York’s American Folk Art Museum, curator and scholar Victor Zamudio-Taylor wrote, “Ramírez may very well become the van Gogh of the mid-twentieth century.” That kind of enthusiasm, plus Ramírez’s regular presence in exhibitions of outsider art and a raging art market, meant the library might not be able to afford to keep the drawing.

But Helena Zinkham, chief of the Prints and Photographs Division, says the family was happy to see Ramírez’s work represented in the library. Money was exchanged. The library won’t say how much, but it was far less than market value.

Victor Espinosa, author of a forthcoming book on Ramírez, argues that these interpretations ignore the obvious: the facts of Ramírez’s life and the recurring iconography of his painting, which offer enough to create meaningful narrative of his artistic career. He believes the new Madonna may not be entirely a Madonna at all, but an image of Ramírez’s wife. Ramírez, a devout Catholic, mistakenly believed that his wife betrayed him by joining government forces during a Catholic rebellion in the couple’s home state of Jalisco, so he was deeply conflicted and may have felt guilty about abandoning her.

“There is something human, something not sacred in the image,” Espinosa says.

This process of interpreting Ramírez — spurred by several drawings discovered in New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 1995 and a cache of some 140 works found in a California garage in 2007 — is helping dismantle the “outsider” label long attached to him. No longer intellectual fodder for mid-century Jungians or treated as hippy heroes of the 1960s and ’70s, outsider artists are being redefined as indistinguishable from other artists. Scholars now play down the sense that he was a victim and stress his pragmatism — doing whatever was necessary to survive in the hospital, finding novel solutions to old artistic problems and reinventing techniques no one ever taught him in mainstream art school.

But that only recasts Ramírez as an artist in today’s mold, when mental illness is no longer mysterious and exotic and artists have abandoned romantic ideas of expression in favor of an ideal of independence, experimentation, discipline and hard work.

And so Martín Ramírez is likely to remain right where he was a half-century ago, admired, studied and a source of delight, perhaps more meaningful and emotionally powerful as long as he remains outside the mainstream canon.