MARTíN RAMíREZ

The Last Works

American Folk Art Museum

45 West 53rd Street, Manhattan

Through April 12

Ricco Maresca

529 West 20th Street, Chelsea

Through Nov. 29

During the American Folk Art Museum’s 2007 exhibition of drawings by the Mexican immigrant and self-taught artist Martín Ramírez (1895-1963), a cache of about 140 more drawings by him was discovered. (In a story that sounds almost too good to be true, the descendants of a doctor who had treated Ramírez in a California mental hospital found the works lying in the family garage.)

The museum moved quickly to put together a sequel; 25 of the newly found drawings, made during the three years before Ramírez’s death from a pulmonary embolism, are now on view. Several more can be seen in Chelsea at Ricco Maresca, the gallery handling the Ramírez estate.

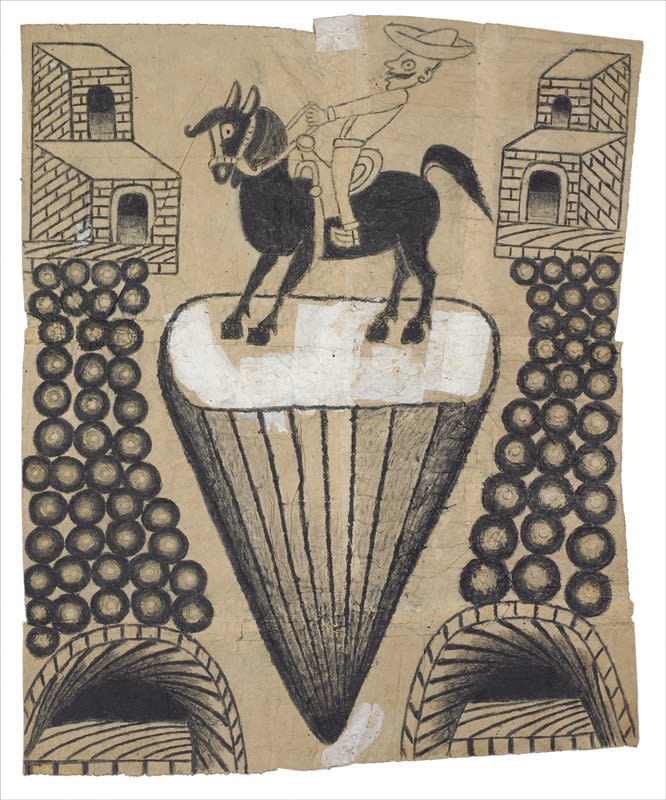

Admirers of the 2007 show will not be disappointed. All Ramírez’s signature themes horses and riders, trains and tunnels, proscenium stages, Madonnas with spiked crowns are here. So are some new ones: magnificent Spanish galleons; exaggerated trumpets

As he had before, Ramírez drew with gouache paint, graphite and colored pencil on odd scraps of paper joined with a paste made from potato starch, bread and saliva. For one particularly resourceful drawing, which depicts a horse and rider on a pedestal, he used paper towels and cigarette rolling sheets. Also interesting is “Untitled (Church Collage),” in which he affixed a photographic image of a white church to pages from a 1947 issue of the travel magazine Arizona Highways.

In the late drawings, however, Ramírez’s quasi-abstract motifs dominate. The architectural colonnades that appear in the backgrounds of earlier drawings receive special attention, as do the steep vertical drops in some of the tunnel pictures. His lines thicken, and their ripple effect becomes more pronounced.

This subtle shift into abstraction is mysterious, even in the context of new biographical research that accompanied the museum’s 2007 show. It could be interpreted as a logical evolution of Ramírez’s art, a manifestation of his paranoid schizophrenia or a response to trends in art and design. (This was, after all, the early ’60s.) Whatever the case, the late drawings are a find. One can only hope that additional stashes of Ramírez’s art will surface.