Then in January 2007 the American Folk Art Museum in New York mounted a retrospective of Ramírez's work. Brooke Davis Anderson, the curator, publicised the show in local papers around Auburn, California, where Ramírez had been hospitalised, in the hope that people would come forward with new undocumented works. After a few false leads, she received a brief e-mail from the descendants of Max Dunievitz, who had been a medical officer at DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn in the early 1960s. When Ms Anderson flew out to California, she discovered the family had more than 120 pictures in good condition, stored in boxes in a garage. These were the artist's last works, created between 1960 and 1963, the year he died.

Now a new show at the American Folk Art Museum features 25 previously unseen pictures from the Dunievitz collection. A cartoonish man on a horse gazes at the viewer, melancholic, vulnerable and isolated on a stage; a train rounds a bend of reverberating curves and enters a mysteriously dark tunnel; arches are arranged in a portentous grid; a Madonna looms tall, beatific and symmetrical, like a chess queen. Seen together, they evoke a narrative of lonesome migration and nostalgia for what was left behind.

Born in 1895 in Jalisco, Mexico, Ramírez travelled to California in the 1920s in search of work to support his family. With no formal education, he busied himself as a sharecropper and day-labourer, working on railways and in mines until the Depression hit. In 1931 he was arrested, haggard, confused and unable to communicate in English. He was diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia and spent the next 32 years in mental asylums. It was during this period, particularly the 15 later years he spent at DeWitt, that he created hundreds of drawings and collages. It was his life's work. He hardly spoke to anyone.

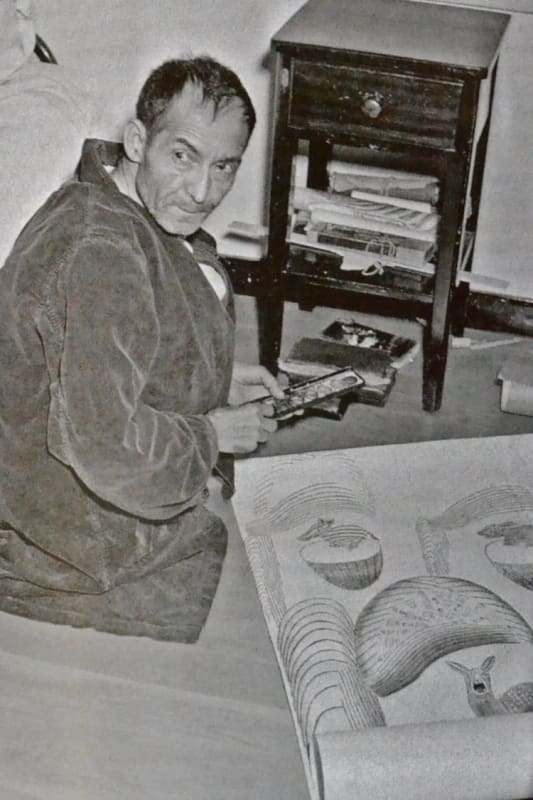

Tarmo Pasto, a psychology professor, was the first person to preserve Ramírez's drawings. Hoping to study the link between madness and artistic creativity, he provided Ramírez with materials and support, and helped to find an audience for his work. Pasto sent the drawings to mainstream museums, such as New York's Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim, but was met with resistance. “This material is very perplexing to everyone,” explained a representative at the Guggenheim. “It doesn't fit comfortably within the canon. It doesn't fit comfortably anywhere.”

Dunievitz also supplied art materials to Ramírez and encouraged him. He dated the drawings, making it easier to study Ramírez's stylistic developments and to analyse the changes. These newly discovered works are better preserved than those from the Pasto collection—more colourful, more vibrant and on crisper paper. But with their lone riders and beacon-like Madonnas, they continue to tell the same story of a man who has travelled so far from home, never to return.