The American Folk Art Museum in Manhattan gets a steady stream of unsolicited e-mail, messages from people claiming to have discovered a self-taught genius sculpturing away in an Appalachian trailer or a pile of masterpieces previously serving as barn insulation.

Brooke Davis Anderson, a curator at the museum, reads all such messages that come her way, even the more improbable ones. And in January, just as the museum was opening its critically praised exhibition of the rare, visionary drawings of Martín Ramírez, a Mexican immigrant who lived in a California mental hospital for more than 30 years, she received a two-paragraph letter that was one of the more incredible she had ever seen.

Sent to the museum’s general in-box, it came on behalf of a retired middle-school teacher named Peggy Dunievitz, the daughter-in-law of a doctor named Max Dunievitz. Dr. Dunievitz served in the early 1960s as medical director of DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, Calif., where Mr. Ramírez lived for many years and died in 1963. The e-mail message, composed by Mrs. Dunievitz’s daughter-in-law, Julia, reported matter-of-factly: “Max is no longer with us, but for the years he worked there, he knew Martín and supplied him with colored pencils and things for his art, and as a consequence my mother-in-law has a collection of Martín’s drawings.”

Ms. Anderson said her heart skipped a beat, but she was conditioned by her years in the field to be highly skeptical of such finds. She asked the Dunievitz family to take pictures of some of the drawings and e-mail them, which they did.

She looked at the pictures. And then she immediately bought a plane ticket to California.

“I think first I actually leaped out of my chair,” she recalled.

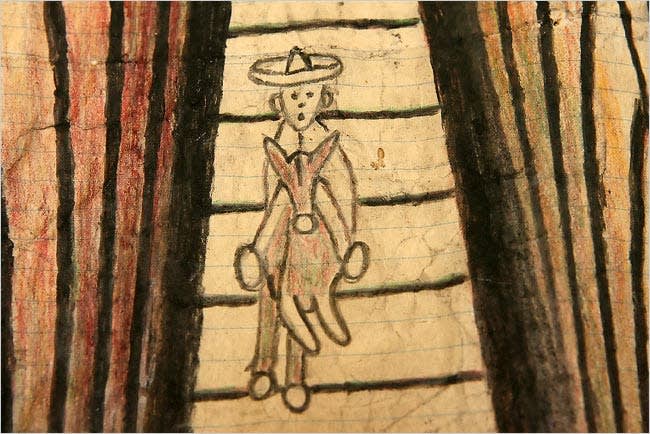

What Ms. Anderson saw were Ramírez’s unmistakable subjects — horses and caballeros, trains, tunnels, ships, Madonnas — and the grand, repetitive lines that were his trademark. And what she found when she got to Mrs. Dunievitz’s house in Auburn was a cache of some 140 of the drawings, all from the last three years of Ramírez’s life, many of them dated and most in great shape, despite lying in a garage for almost two decades.

It was an astounding discovery for an artist whose known body of work had previously numbered about 300 drawings and collages, collected by a psychologist, Tarmo Pasto, who befriended Ramírez and championed his work beginning in the 1950s.

Mrs. Dunievitz, 73, had contacted the museum after reading a newspaper article about the Ramírez show in New York, and had been largely unaware of the artistic or monetary value of the drawings; some Ramírez works have sold for more than $100,000. She has now become the holder of an important, lucrative art collection, which she and her elder son, Phil, and Julia, his wife, are hoping to sell.

They said they are also planning to give at least three works as gifts to the Folk Art Museum and, along with a lawyer and a New York dealer they have chosen, are discussing plans to use some of the money to honor Ramírez and his surviving family members, who do not own any of his works and have never benefited from his rising profile in the art market. The Folk Art Museum is also planning an exhibition of many of the new drawings for next October that it hopes will show how Ramírez’s work matured, becoming more confident and abstract in its final years.

The survival of the drawings is all the more unlikely because, after Dr. Dunievitz’s death in 1988, they were thrown in a trash pile by his relatives as they sorted through the possessions in his basement.

“They basically made a blind assessment: ‘All this stuff needs to go in the trash,’” said Phil Dunievitz, 42, who had seen the artworks many times in his grandfather’s house when he was young. Instead, he gathered them all up, rolling them and putting them into several long-stem-flower boxes in his mother’s garage.

They were later transferred to an old box that sat atop her garage refrigerator for years, “with a sleeping bag on top of that,” Mrs. Dunievitz said. “And sometimes the cat slept out there on top of it all.”

“Somehow, anytime the garage was cleaned out,” she added, “they miraculously didn’t get thrown out.” In the 1990s she came across a Ramírez while visiting the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Va., and talked to a curator there, telling her that she had some Ramírez drawings of her own. But after she left, she never followed up.

“I would have been elected procrastinator of the world if I ever got around to mailing the paperwork in,” Mrs. Dunievitz said.

Ms. Anderson, who had organized the Ramírez retrospective, first saw many of the drawings after they had been moved from the garage to a spare bedroom inside the house and displayed atop twin beds. She was more than ecstatic. “Brooke kept saying: ‘Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Oh, my God,’” Mrs. Dunievitz said. “I thought she was praying.”

In a recent interview in a Brooklyn warehouse where the drawings have now been moved for safekeeping, Ms. Anderson, the director of the museum’s Contemporary Center and Henry Darger Study Center, said her reaction was probably a little bit over the top.

“This is huge for us,” she said, adding, “I was always convinced that there was work out there in basements and attics that had been collected by doctors or nurses or janitors.”

Ramírez left his small ranch in the Jalisco region of Mexico in 1925 to look for work in California. He became homeless, and in 1931, appearing to be confused and unable or unwilling to communicate in English, he was picked up and committed. He never returned to his wife and four children back home, spending his last three decades in psychiatric hospitals.

Frank Maresca, the art dealer whose gallery, Ricco/Maresca, was chosen over two other competitors by the Dunievitz family to represent the work, said the discovery of such a huge amount of new work by an artist of Ramírez’s stature “is really as rare as Tutankhamun.”

It is even more significant, he said, because it will allow people to see a clear arc to Ramírez’s output. “What you see in the later works is a stronger degree of stylization — everything becomes more abstracted and experimental,” he said.

Mr. Maresca, Mrs. Dunievitz and her son said they had only recently begun discussing what might be done for Ramírez’s surviving family, which includes a daughter and many granddaughters and great-granddaughters. The likely plan will be to create some kind of an education and arts foundation instead of giving works or money directly to the family.

“There are more than 50 of them,” Mrs. Dunievitz said of the family. “How do you slice a pie that thin?”

But her son, who runs a tree-removal business near Lake Tahoe, said he still held out some hope of donating some work. “The family doesn’t even have one piece of his art, and that kills me,” he said.

Contacted by phone, one of Ramírez’s great-granddaughters, Martha Bell, a financial coordinator at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said she and her sisters were simply happy that more of the work had been found in good condition to add to Ramírez’s legacy.

“This is music to my ears,” she said. “We’re so proud and so excited.”

Asked how the money from the drawings might affect his life, Phil Dunievitz said he did not think it would change much. “We might be able to buy a house,” he said, “which would be nice.”