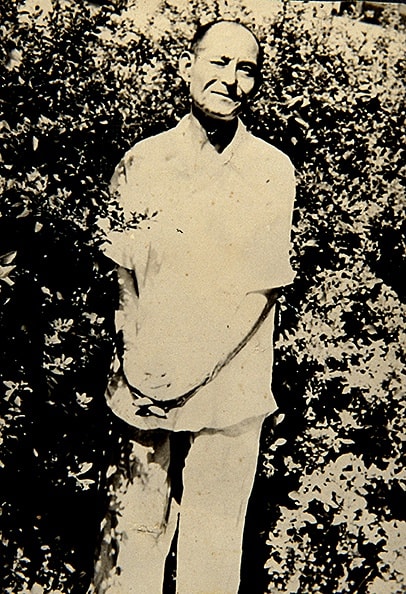

IN 1925 Martín Ramírez (1895-1963), the great self-taught draftsman, left his small ranch in the Jalisco region of Mexico for work in the promised land of the United States. He never returned to his wife and four children back home, spending more than three decades confined to psychiatric hospitals after being picked up off the streets of California in 1931: jobless, homeless, confused and unable to communicate in English.

But in the 300 drawings Mr. Ramírez created over the last 15 years of his life — after being sent to DeWitt State Hospital near Sacramento with a diagnosis of catatonic schizophrenia — he revisits the scenes of his young adulthood: the horse and rider, trains and tunnels, Madonnas, animals and landscape of his native Mexico.

“He was a landscape artist obsessed with memory,” said Brooke Davis Anderson, director and curator of the American Folk Art Museum’s Contemporary Center. “Mexico breathes in his work.”

“Martín Ramírez,” opening Tuesday at the museum with 97 of these works (including the untitled one below), moves beyond the traditional view of Mr. Ramírez as a deaf and mute schizophrenic artist. It interprets his artistic merits by looking at the work as art shaped by poverty, immigration and institutionalization.

He was making art before his time at DeWitt; he decorated his letters home and made drawings at Stockton State Hospital, where he was first institutionalized. But there is no record that any of that work survived. He was never interviewed.

After his transfer to DeWitt in 1948, he met Tarmo Pasto, an artist and psychology professor at Sacramento State College, who began to collect Mr. Ramírez’s drawings. Mr. Pasto introduced him to local artists and to some of his students, including the painter Wayne Thiebaud, who recalls having brief conversations in Spanish with Mr. Ramírez.

Mr. Pasto also arranged for Mr. Ramírez’s work to be exhibited, which he was aware of from newspaper articles the hospital saved. Reviewing a group show at the de Young Museum, Alfred Frankenstein of The San Francisco Chronicle called Mr. Ramírez the “most striking artist” in the exhibition, one with “an innate gift for form, color and pictorial organization” whose art “went deep into recollections of his country’s folk art.”

But the glory that Mr. Ramírez may have longed for never arrived. In accordance with California laws protecting the privacy of mental patients, he could not be mentioned by name. Instead he was called simply, “an aged Mexican.”

He fared no better in New York. In the 1950s, Mr. Pasto sent a tube holding 10 of Mr. Ramírez’s drawings to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum for a show that never happened. They were put into storage. The museum now has the largest public cache of Mr. Ramírez’s work — though the drawings came to light only 40 years later when an intern stumbled upon them.