Earlier this year, I received an e-mail from the daughter-in-law of a Dr. Max Dunievitz, who had been medical director of Dewitt State Hospital, a mental hospital in Auburn, Calif., in the early 1960s.

I had never heard of Dunievitz, but I knew that Dewitt was the hospital where the Mexican American artist Martin Ramirez (1895-1963) had lived for 15 years.

At the time of the call, I was organizing a Ramirez exhibit at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. Dunievitz was calling with the classic curator’s dream: to tell me about a group of Ramirez’s drawings in her possession, found in a box above a refrigerator in her garage. I jumped on a plane to California to see the artwork and verify that it really was by Ramirez -- and was shocked to learn that this newly discovered collection was significantly larger than she had suggested. There were more than 100 drawings, a remarkable find given that Ramirez’s known body of work had consisted of about 300 drawings and collages.

Ramirez, an immigrant from Mexico who lived in California mental asylums for more than three decades, created drawings of remarkable visual clarity and expressive power. In the early 1950s, Dr. Tarmo Pasto, a visiting professor of psychology and art, saw Ramirez’s drawings at Dewitt, where the self-taught artist lived from 1948 until his death, and recognized their artistic significance. Pasto supplied him with art materials, and Ramirez became the subject of Pasto’s research into the relationship between mental illness and creativity. The known body of work was primarily collected and promoted by Pasto.

No one realized that Ramirez continued to draw after Pasto’s visits with the artist became less frequent in 1960; those drawings made in the last three years of Martinez’s life were saved by Dunievitz and ended up with his children when Dunievitz died.

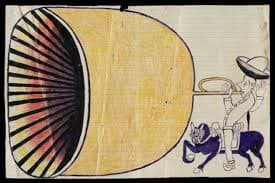

In these newly found works -- several of which are displayed on these pages -- the same motifs and themes are prevalent that Ramirez previously explored in his drawings: trains and tunnels, Mexican landscapes, Madonnas, animals and images of horses and riders. However, there are some obvious differences, such as the classic horse and rider, jinete, who now plays a highly stylized trumpet instead of sporting a gun, or the emergence of a deer isolated and sitting alone within a stage-like setting.

There are also stylistic developments, such as a greater use of color and a more frequent exploration of abstraction. His well-known train-and-tunnel motif has been transformed into a repetitive design of abstract arcades and tunnels, rendering the train a secondary subject. Ramirez continued to work with found paper, drawing paper and hospital examining room paper; these new drawings range in size from 2 to 18 feet long.

Remarkably, because they were stored in a garage for several decades, the drawings are in good condition, and they will greatly increase public knowledge and appreciation of the complex, multilayered artwork of this master draftsman.

Brooke Davis Anderson is curator and director of the Contemporary Center at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. In October, the museum will unveil a selection of about 30 of the later Ramirez works.