Tino (“Rosie”) Camanga (1910-?) moved to Honolulu from his native Philippines sometime prior to World War II. He worked for a time as a photographer, probably in one of the souvenir photo booths where one could have a picture taken against a painted backdrop of a prototypical Hawaiian scene¬: grass shack, Diamond Head, etc.—often accompanied by a “hula girl,” complete with grass skirt, provided by the photo operator.

After observing fellow Filipinos tattooing in the many shops in the downtown/Chinatown area, Rosie was granted a part-time job in 1944. He told the shop owner that the job was easy, since the work was all done with stencils; he’d “sketched” his whole life and knew he could do it. The owner scoffed at this and said he’d pay him $50 if he could put on a credible tattoo. Rosie demonstrated his ability by putting a piece on his own leg and was given the job. In wartime Honolulu, hundreds of thousands of military personnel swarmed through the downtown zone, boosting business to incredible levels in the penny arcades, bars, dance halls, government-sanctioned whorehouses, and tattoo shops that blanketed the area. After a couple of years, Rosie had drawn about 400 sheets of flash and left to open his own shop. He tattooed continuously in a variety of locations around the Hotel Street (downtown) area until 1991. After a short hiatus, he re-opened his final shop in a former shoeshine stand on the edge of Chinatown. As business was virtually non-existent for him at this point, he retired for good but kept on drawing.

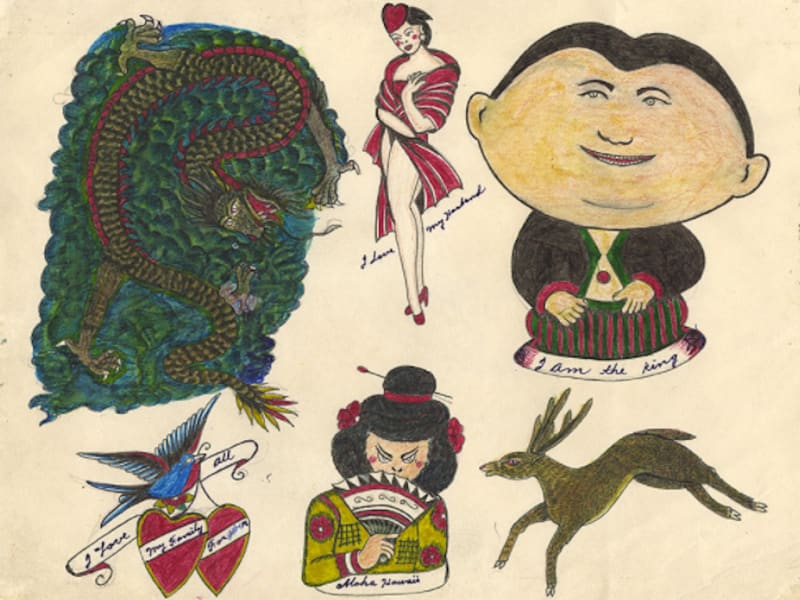

Sailor Jerry Collins introduced me to Rosie in 1968. At that time, they had the only two tattoo shops on the island of Oahu, situated about a block apart. Jerry realized Rosie’s tattoo ability was primitive, to put it mildly, but respected him for his sobriety and industriousness. Rosie’s tiny shop was overlaid with his distinctive hand-drawn flash, layer upon layer, in a style unlike anything I’d ever seen. My early amazement and condescension at his raw version of classic tattoo design gradually gave way to unqualified admiration. When he began selling off his shop contents in the early 1990’s I bought much of his flash and brokered it for him at art galleries on the mainland. Rosie was a complete original. Humorous and tough-minded, he survived for decades in control of his own game in a volatile honky-tonk environment. A sense of sly humor helped keep him afloat—once he told a health inspector that the powdered charcoal used to apply stencils to the skin came from the barbecue. Rosie’s flash, from early examples (none of his work is signed or dated, but clues exist from dates or events depicted in the designs), segued from standardized versions of classic tattoo designs to eccentric and mysterious scenarios that were his alone. The format of a sheet of flash, crowded with multiple images, or the notion that something might be appealing to someone to wear indelibly for life, were mere jumping-off points for the world he created. He often collaged sheets with images he liked, which he’d clipped from a magazine or assembled from previous designs, which regularly depicted things and sentiments never seen in any other tattoo context. He continued to draw after he stopped tattooing, using the flash format for ever-more unexpected forms. The phrases accompanying the pictures are rendered in the artist’s adopted and imperfect English, often resulting in a hilarious and mysterious poetry of meaning. The overall effect is a wacky mixture of cartoon humor, lofty emotions, menace, and smoldering sexuality.