Born in Mexico, Martín Ramírez came to America in 1925, where he worked difficult jobs as a miner and on the railroad. In 1932, California police found him wandering in a dazed state, which resulted in him being committed to two psychiatric hospitals. Forcibly detained, he was diagnosed as a schizophrenic (a diagnosis many challenge) and spent the last 15 years of his life as an inpatient. At the DeWitt State Hospital in Northern California, he made some three hundred drawings, characterized by their remarkable architectural structure and rhythmic force. His work seems to have arrived on the page free of influence. Described as an outsider artist, it is more accurate to understand Ramírez’s art as so independent that conventional descriptions and categories fall by the wayside. Many now consider Ramírez a preeminent artist, someone whose work cannot be relegated to the margins. Despite the tragic circumstances of his later life, the stunningly forceful art currently on view at Ricco/Maresca locates him as a central figure in a rapidly expanding canon.

Ramírez’s works often include structural details developed by repetitive lines. Untitled (Trains and Tunnels) A, B (ca. 1958–61) is divided into five sections: the first, third, and fifth components consist of columns decorated by reiterations of downward looping lines. Two trains, set about halfway up the columns, make their way toward tunnels located at the left edge and center of the composition. Between these three parts of the composition, there are two larger tunnels, rendered by repetitive lines whose curves move upward, creating a ceiling. The drawing is highly stylized, yet the trains and tunnels are easily recognizable. The combination of a nearly abstract description of things we can understand is central to Ramírez’s art. In an untitled work from 1960 to 63, created with gouache, colored pencil, and graphite, Ramírez presents a series of vaults, three groups of four arches stacked one on top of another. On the very top there is a line of much smaller vaults. These structures are determined by dark red stripes, in between which are areas of light blue-white. In the spaces the vaults open into, we see small areas of flooring and, deeper within, darkness.

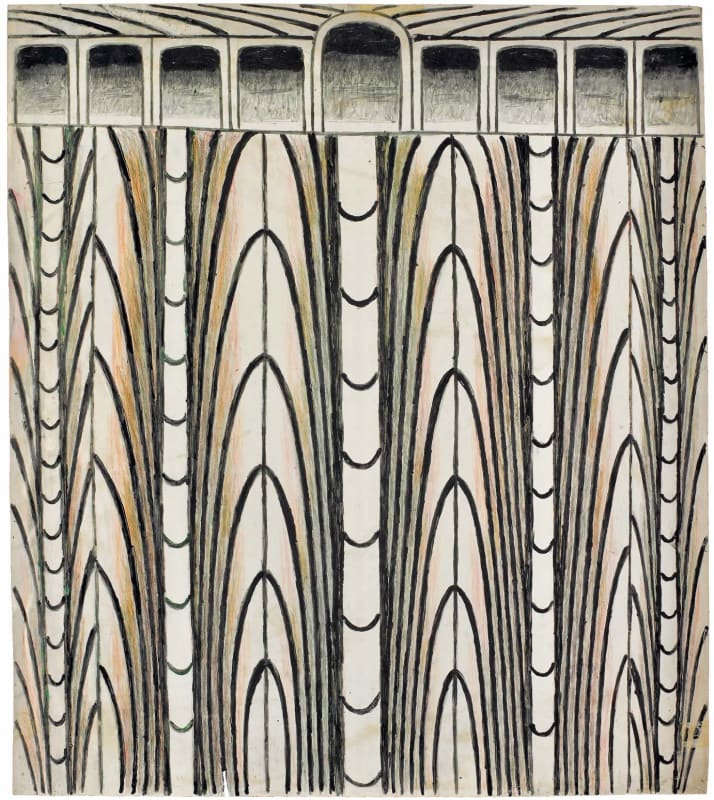

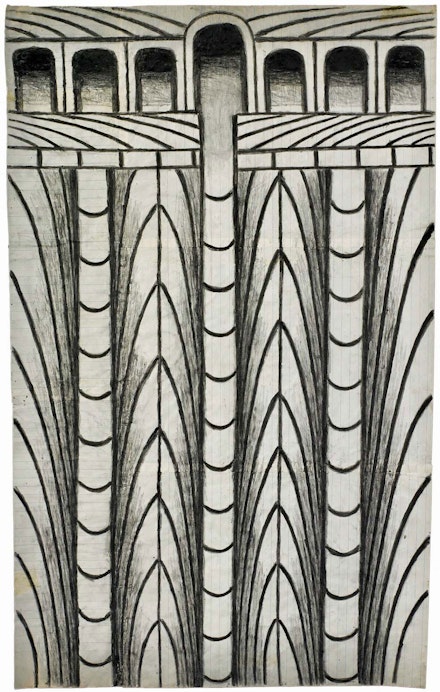

In Untitled (Abstraction with Arches) (ca. 1960–63), Ramírez again creates something both non-objective and recognizable. It consists of four columns of rising, overlapping ovals, with a line running up the middle of each form. These columns are separated by thin vertical spaces embellished by downward curving lines at regular intervals. On the top, viewers see a row of arches, the central one with a rounded top. On either side of it, there are four arches with flat ceilings. This drawing truly borders on the abstract and testifies to Ramírez’s penchant for imagery whose systematized order comes close to patterning even as it also reads as representation. An untitled work from 1960–1963, unusual for its yellow coloring, includes three rows of arches, two larger rows supporting smaller, more numerous arches at the top. Slightly curved lines on top of the arches extend into a suggested depth, indicating, perhaps, a long roof.

It is a bit difficult to characterize Ramírez’s structures—not quite buildings, but clearly aligned with them. Although the artist worked at a time that saw the beginnings of our contemporary culture, there is something both ancient and properly modernist about his efforts. His structures are monuments not tied to a particular time. Perhaps the key to his achievement is a predilection for symmetry, related to architectural form, that effectively combines the old with the new. Ramírez’s reputation has risen quickly—deservedly so. He doesn’t necessarily fit in with established practice, but neither is he an outsider artist. His scenarios are powerful in their imagery, and the overall pattern of the drawing is as important as the rendered image. An impulse to abstraction always coexists with things we recognize by sight. It is Ramírez’s ability to effect this merger between schematic markings and a stylized realism—and to do it in a way that is deeply unfamiliar—that makes him so wonderfully effective as an artist.