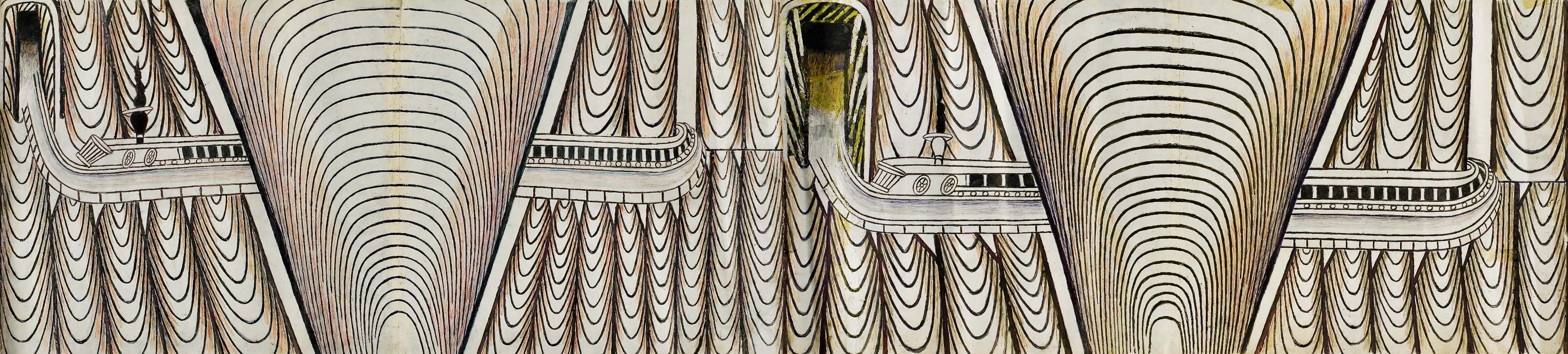

Two locomotives billowing black smoke dart in and out of mountain tunnels, snaking through a psychedelic topography of strobing parabolas hatched with delicate traces of yellow pencil. The drawing, Untitled (trains and tunnels) A, B (all works cited, ca. 1958–61), was perhaps the most electrifying piece in “Memory Portals,” an exhibition of Martín Ramírez’s art at Ricco/Maresca. The train as motif, inset here with dark windows that echoed the punctured building facades appearing throughout the show, is a recurring feature of Ramírez’s work, an emblem resonant with the themes of itinerancy and displacement that mark the artist’s biography.

In brief: Ramírez was born January 30, 1895, in Tepatitlán, Mexico. In 1925, he left his wife and daughters on their small ranch in Los Altos de Jalisco, seeking work in the United States. Six years later, he was arrested in Stockton, California, and committed to the city’s mental hospital, where, in a now-disputed diagnosis, he was pronounced a catatonic schizophrenic. Save for a handful of breakouts, Ramírez never again lived outside of a psychiatric ward. In 1948, he was transferred to DeWitt State Hospital, where Tarmo Pasto, a professor of art and psychology at Sacramento State College, admired and encouraged his artmaking, laying the groundwork for his eventual canonization, facilitated by promotion from Chicago Imagist Jim Nutt and gallerist Phyllis Kind, as an “outsider master” of American art.

In his 2015 book on Ramírez, sociologist Victor M. Espinosa criticizes the persistent framing of his work as “a passive manifestation of mental illness,” which, he argues, obscures its particular cultural and biographical significance. The symbol of the train, for example, may refer to Ramírez’s border crossing by rail, his time spent as a laborer for the Southern Pacific Transportation Company, or the freight car he is believed to have hopped during one of his aborted escapes.

The dominant imagery in the exhibition, devoted, per the press release, to Ramírez’s “recurrent and mysterious depiction of arches, doorways, and portals,” was harder to pin down. In most of the works on view, the artist arranged the drawing surface—often large, horizontal, and pieced together from smaller sheets of lined paper—into an irregular grid perforated with various fenestrations. This structure yields an abundance of graphic effects, from the syncopated rhythm of differently scaled colonnades in 007 ABC, Untitled (Arches), to the meander of ogees in Untitled (arches). Sometimes austere vaults open onto moments of sweltering color, bringing to mind de Chirico’s piazzas wrenched from linear perspective. More often, they reveal caliginous passages of gray and black. Ramírez’s arcades, as Espinosa has suggested of similar forms, may represent the custodial space of the Stockton State Hospital. Nonetheless, they invite competing metaphysical interpretations, intimating both a total architecture of confinement and a mind palace of innumerous thresholds and interiors, a spatial imaginary of the unconscious.

Does such a reading flirt with discredited myths of visionary genius? Since Ramírez’s canonization, Espinosa writes, his work has been “appreciated to the point of fetishization on the basis of its supposed correspondence to an interior psychology,” eclipsing the dynamic social formations—from rural poverty and devout Catholicism, to economic migration and racialized exploitation, to the carceral care of two psychiatric facilities and the developing fields of art and occupational therapy—that conditioned his production. For a more situated view of Ramírez, we might turn to another work called Untitled (arches), which features a peculiar detail: a vertical strip of paper attached to the top of the composition like a makeshift suspension cable. This extremity may offer a clue to the institutional context that both curtailed his freedom and shaped his art, which—contrary to the perceived hermeticism of “outsider” artists—he eagerly shared with others. Pasto recalls that, when showing his work, Ramírez “would place his drawing on the edge of the table and place a box of colored pencils on the small piece of paper which he had glued to the top of the picture. This would permit the drawing to hang down. . . . He looked at me to see if I approved his picture. I told him it was wonderful. At that he would roll up the drawing and hand it to me with a smile on his face.”