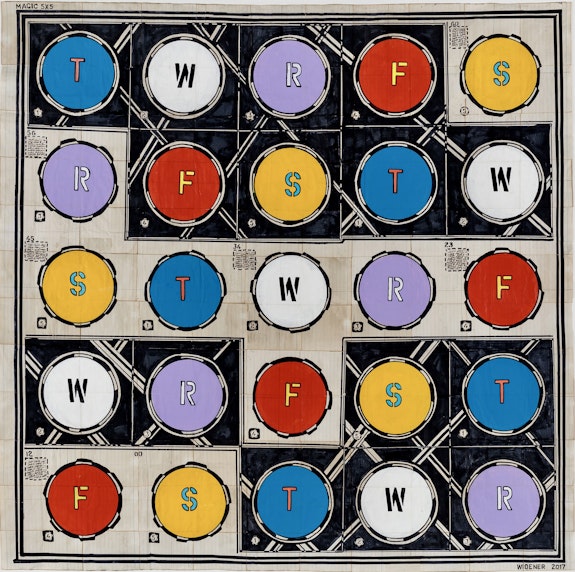

George Widener, Magic Circles, 2017. Mixed media on paper, 45 1/2 x 46 3/4 inches.

George Widener is a calendar savant, a term I was unfamiliar with; perhaps better-known savant categories include musical savant and autistic savant. Typically, savants have an extraordinary ability involving calculus and memory together with unconventional social skills that inhibit a conventional life, but all savant descriptions fail to explicate just how extraordinary the people who carry this title are. Widener’s ability is to be able to identify, for example, the day of a week of any given date within certain parameters—a particular decade, say. For Widener, numbers like those from a car license plate will frequently appear to him as a calendar date.

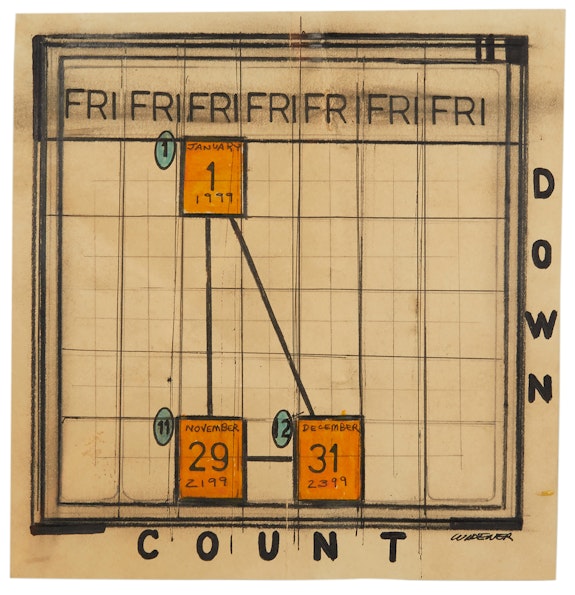

George Widener, Count Down (Week of Fridays), 2010. Mixed media, 8 x 7 1/2 inches.

Widener was born in Cincinnati in 1962, and after serving in the US Air Force in what was then West Germany as part of NATO forces, he planned to become an engineer but was detoured from this by his intense focus on dates, numbers, disasters, and automatic drawing. Consequently he took odd jobs and often slept in homeless shelters, all the while keeping notes and developing his own counting system. After being diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, Widener was referred to a Tennessee vocational rehabilitation center; it was here that his drawings were first discovered, and later exhibited. His sophistication as an artist is self-evident, and he has said of his drawings:

The subject of my work is that of time and, more precisely, the shifting and symmetry of time—which I believe occupy every individual’s subconscious. I believe that truths are often revealed in unexpected divergent events, the past and the future are joined in subtle ways. I’ve been interested in disasters as an anthropology project of sorts.

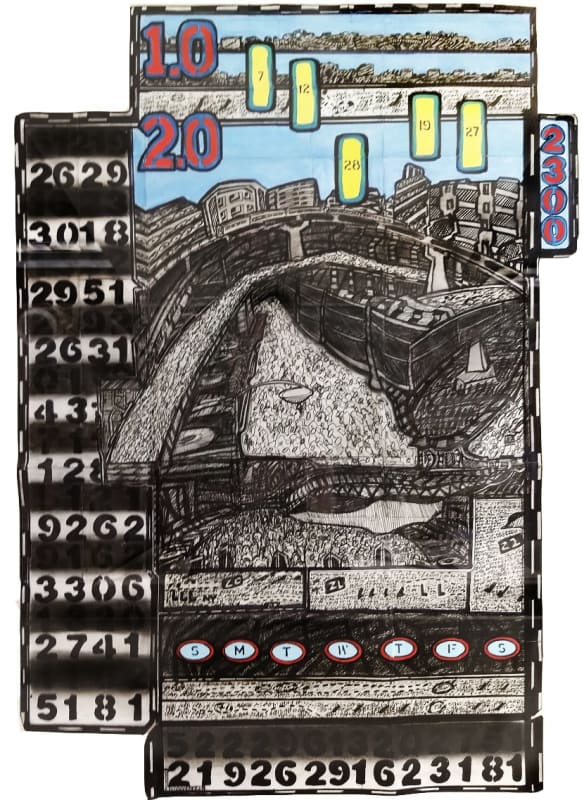

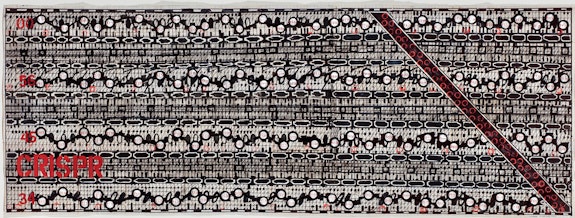

There are fifteen framed works displayed at Ricco/Maresca, all mixed media on paper and dating from 2010 to 2021, presented elegantly across white or black walls to striking effect. What is notable immediately are the diagrammatic schemas of repetition and pattern consistent in all the works comprising numbers, letters, and geometric shapes. The impression looking at one work after the other is of an abstract process made visible, an index of mental processes—recall and calculations, in streams and grids across the surface of each work. We can see these workings in CRISPR (2015), its title stenciled in the lower left corner of a field of pulsing rows of biomorphic shape accompanied by numbers that appear as a texture from a distance. A black diagonal with red open circles crosses from left to right like a slice into the material. The title references the sequences of DNA found in genomes that are used in both gene therapy and gene editing. Sequence, of obvious interest to a mind like Widener’s, is here foundational to the work’s composition and meaning. Board games come to mind with MAGIC CIRCLES (2017), the red, yellow, and blue brightly colored discs, each containing a stencil-style letter and diminutive number representing a permutation or registering a code that can be imagined in other constellations in other circumstances. The discs are bounded by enclosing circles of alternating black and white segments within the line of the circle and rest atop an uneven checkerboard of black and white squares.

The complexity and layering of relating systems is evident in other works, too, and impresses in its formal expression of the entanglement of subsisting methods of externalization: math, color relationships, indexical systems, and language’s statements, names, letters. This exhibition is an important introduction to his specific aesthetic.