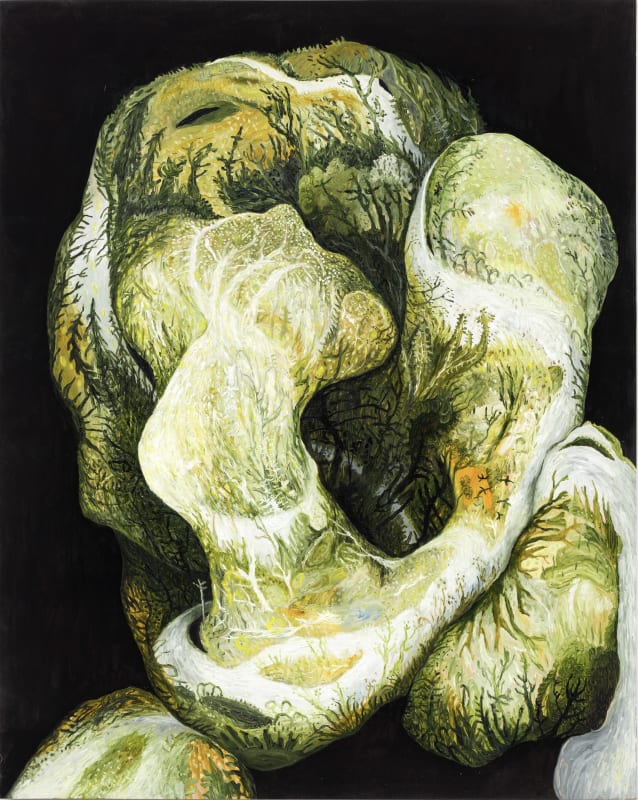

Laver depicts an elastic and sensile landscape, one that moves and shifts upon examination like a quark. Like Bruno Latour, Laver seems to question what the microscope and the observational instrumentations of the Enlightenment have done to our ways of being in the world, how they exteriorized and flattened our experience by making its value bound solely to the task of understanding. Laver meddles with landscape as a genre code, while also using it as a psychic mirror, casting a reflection of interior states with the indulgence and emotional register of Morris Graves. Don’t think twice, it’s alright (2022) strikes the plangent chord of the Bob Dylan song that provides the painting’s title by impossibly contorting the landscape into a tangled form. The landscape is painted like a projection map over bodies holding each other, holding themselves, being held by, and holding.

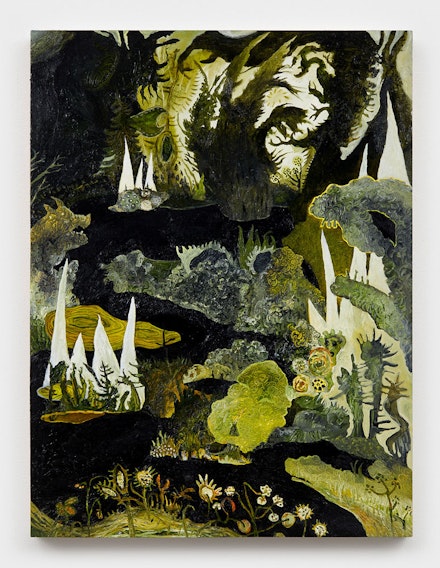

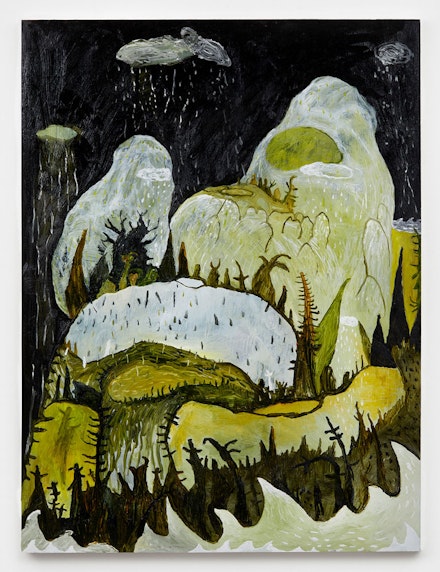

At the extremes of his range, if it weren’t for the use of the crucial color green the paintings might not be recognizable as landscapes at all. Ghost Mountain Deluge (2022) could be a Guston painting, if not for its use of green instead of red. The bean shapes of the mountains seem like a direct homage to Guston’s self-portraits that reduce his subject to a sullen eye. Throughout, Laver doesn’t personify nature in angelic terms. Often, he sets about recognizing and finding the writhing or snarling forms that the landscape assumes. In some paintings, Laver takes the sawtooth shapes of Burchfield to the nth degree, applying a dramatic texture that Burchfield wouldn’t have ventured. In his “Thicket” paintings (2021), the treeline forms menacing entrances into darkness. After all, if we are to give nature its own agency, we must acknowledge its uncompromising hostility towards us as well.

The underlying motives of the series are perhaps made most clear in paintings like Down by Okkervil River (all silent, slow, and black) (2021), where the landscape transforms into the shapes and fangs of wolves, lizards, and ghoulish shadows. This literalization of the artist’s taste for pareidolia presents us with the reality that the landscape is always constructed. The naive or authentic experience has been made impossible—the expectations we develop for what is scenic, what is remote, or what is wild disallow it. We are taught to see nature as a nurturing Mother Gaia, perfectly innocent, to act as a foil for human consumption. The painters of history scattered pareidolia, image moralities, and symbols across the natural world. We see the architectures of the vista wherever we look.

Laver’s refreshingly radical subjectivity throws our own biases and ecological views into striking relief. Laver’s endless ability to make paintings from the trails of the forest, the license he gives himself in exploring the landscape as a genre form, delivers visual pleasure within the gallery, and builds a sharp critique beyond it. Our enjoyment reminds us that every window has become a vista, that we see shadows of ourselves in the trees and the forest. We understand nature as a destination instead of a journey, and we always have. After all, before Instagram there was the Claude glass. And before that, nature was painted from the safety of the artist’s studio, until oil paint could be easily carried in zinc tubes. The inclination to reduce the world into an image after the enlightenment, to fashion it into something picturesque, was a shift away from the first animist leanings of the cave painters, and the expansion of the self by philosophers of antiquity through their imagining of the anima mundi. This utopic possibility of kinship with the natural world, of being with and in, now finds expression in Laver’s work as well.