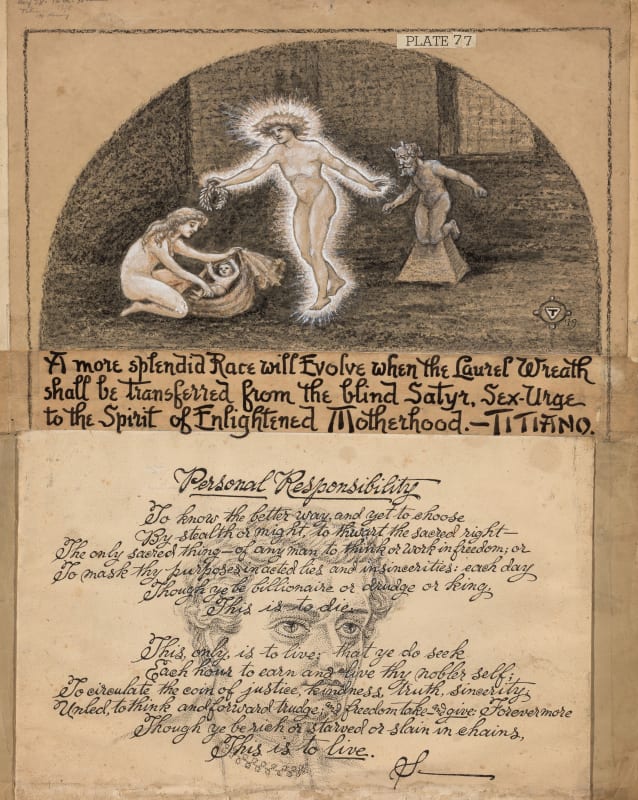

An androgynous youth levitates beneath a stone archway, charged by a halo of energy. Rainbow interference shimmers around their sexless body, while a halo of golden hair floats around their head, suggesting zero gravity. Beneath this ecstatic, Hermetic figure is an inscription: “When I next pass through the dark portals into rebirth on Earth, there to apply the greater principles learned here, I shall first choose a noble mother.”

With its resonant jewel-tones, architectural frame, and arcane text, this illustration by Grant Wallace (1868–1954) recalls sixteenth-century alchemical illuminations in whose symbolically-laden images the secrets of transmutation were thought to be embedded. It is a stylistic outlier within the group of portraits by Wallace currently on view at Ricco/Maresca Gallery, which comprise the first-ever gallery show of his art. A majority of the thirty-one works here are rendered in a luminous Art Nouveau style more characteristic of the period from which they emerged, between 1919 and 1925. Statuesque, somewhat genderless figures adorned with feathers and whiplash lines show the influence of Egyptomania and Romanesque motifs popular in the 1920s—and yet, they don’t feel constrained to that era, either. There is something proto-psychedelic about Wallace’s characters, whose giant, shimmering eyes evoke Grey Aliens or even anime.

One explanation for the transhistorical character of these portraits is that they were channeled from a realm outside of time. Grant Wallace was an early-twentieth century settler of California, a professional journalist, and a self-taught artist and telepath who spent much of his later life engaged in a mediumistic practice he called “mental radio.” The characters in his art are based on transmissions he received, as are the calligraphic messages in which they are embedded, which herald astral projection as a means of spiritual evolution: “Telepathy is the fourth dimension of speech,” one text explains, “It is the language you must use after you ‘die.’” In an incomplete frontispiece, Wallace titled his project “Over the Psychic Radio: An Astral Album of Autographic Scripts and Self-Portraits.”1 Emerging a century after their creation, these works provide an interesting case to examine the vital relationship between art and esoteric practice.

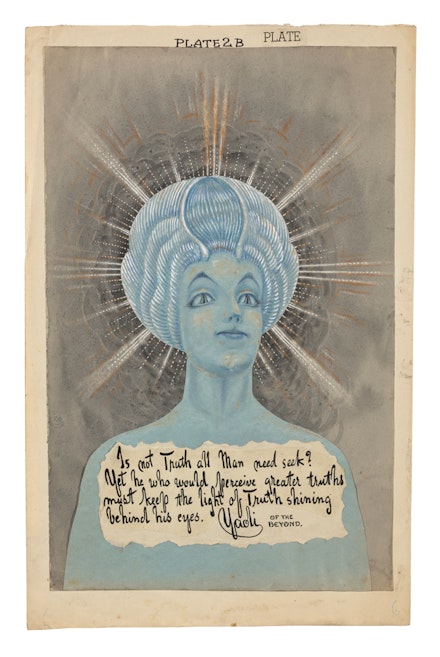

Grant Wallace, Yaoli of the Beyond, ca. 1919 - 1925. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 16 x 10 1/4 inches. Courtesy Ricco/Maresca Gallery.

Of all the forms of fine art found in Chelsea today, the art of communicating with spirits remains little-represented. Ricco/Maresca is one of the few galleries known for bolstering self-taught artists. The current show unveils a practice which has been mostly hidden in Wallace’s family archive since his death. However, it would be a mistake to label his work “outsider art.” On the contrary, Wallace was part of a zeitgeist that aspired to bridge the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by elevating the spiritual consciousness of the western psyche. Institutionalized in the Theosophical, Spiritualist, and Anthroposophical movements, this “new age” mentality encompassed many individuals around the world, including many artists. One contemporary of Wallace was the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), who has become well-known only since her sensational 2019 Guggenheim show, Paintings for the Future. Klint produced some of the first abstract paintings in modern Western art, and she attributed her inspiration to the instruction of spirit guides whom she engaged through séance, trance, and automatic drawing.

There’s something in the aether lately—perhaps activated by the revelation of af Klint’s paintings—which is calling the art world to reconsider assumptions that visionary practices belong on the fringe of the canon. Multiple major exhibitions this year have surveyed the mystical influences on modern and contemporary art, including Peggy Guggenheim Collection’s Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity and Minneapolis Institute of Art’s Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art, not to mention The Milk of Dreams, the 59th Venice Biennale’s international art exhibition, which centered inherently magical conceptions of transformation and enchantment.

Ricco/Maresca has worked to place Wallace in this nourishing context, co-organizing an online symposium with Morbid Anatomy for the exhibition that featured a survey of art and psychism by historians Susan Aberth (Not Without My Ghosts, 2020) and Robert Cozzolino (curator of Supernatural America).3 Touching on Georgiana Houghton, Emma Kunz, and Madame Fondrillon, they traced a lineage of art that has long been stigmatized, one which is predominated by women and individuals deemed mentally ill. As Cozzolino put it, “Embracing the spectral integrates artists who have summarily been rendered invisible—revenants hovering at the edges… Ghosts and extraterrestrials, UFOs and demons, telepathy and magic—they tap into cultural fears that impede empathy, understanding, and analysis.” What was once marginalized remains threatening to a modern (white, male) conception of the avant-garde, namely the possibility that genius is not something one is, but something one might experience—in other words, that creativity is a fundamentally receptive quality.

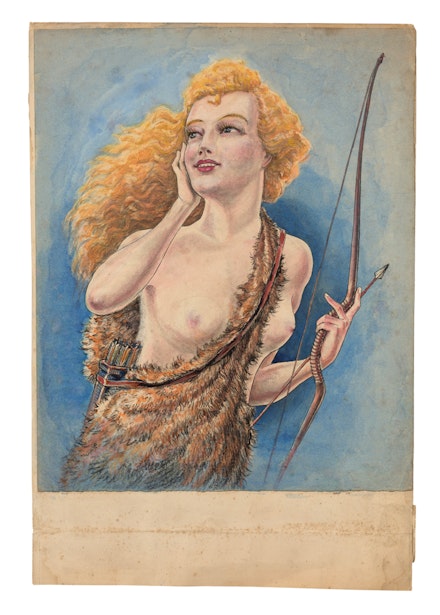

Grant Wallace, Artemis, ca. 1919 - 1925. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 19 1/4 x 13 inches. Courtesy Ricco/Maresca Gallery.

And what was Wallace receiving? The overarching message of his transmissions is a potentially challenging one—in a word, truth. “Is not truth all man need seek?” asks one of Wallace’s spirit guides; “He who would perceive greater truths must keep the light of truth shining behind his eyes.” Another spirit describes higher realms of insight available only to “those who have time and courage enough to seek and face the Truth, and industry enough to prove it.” Truth appears throughout the body of work as a utopian concept, one which may have felt endangered to Wallace himself, a professional reporter at the height of the yellow journalism era. In our own global communication age—heralded by the very technology on which he based his machination of the psychic radio—truth is not merely threatened, but arguably extinct. Somewhere between quantum physics and fake news, truth became an alien. Must we draw down its ghost from a higher realm?

In the business of calling up spirits, however, one must remain wary of false prophets. Among the most amusing portraits by Wallace is Artemis (1919–25), half-Gibson Girl and half-Hollywood starlet, who appears to pose for the camera, her face glazed with a vacuous smile. Motion picture was the other cutting-edge technology available to Wallace, who apparently wrote and produced two silent films before 1920. His Artemis suggests an awareness of fault lines in the California utopianism that surrounded him, which prophesied the celebrity age in which we now live. This bimbo beauty may carry the name of the virtuous goddess of the hunt, but is not truly she. It’s significant that Wallace refers to these spirit characters as self-portraits, for receiving outer voices is also a matter of discerning inner ones.

The private pursuit of spiritual advancement is characteristic of sacred art practices. Hilma af Klint created her radical paintings largely in private, even ensuring that they could not be publicly exhibited until twenty years after her death, believing they would not be understood in her time. Wallace appeared to have tried little during his own life to publicize his spirit transmissions, which he sometimes referred to as “the Big Work.” One San Francisco newspaper ran a story on his psychic innovations in 1923 with the headline, “ALPHABETS FROM PLANETS; MESSAGES FROM FAMOUS SPIRITS.”

According to Wallace’s great-grandson, however, the artist was dissatisfied with the Sunday-paper interest piece, which portrayed his work with only a winking credulity.

But it hardly mattered, because these were transmissions for the future. Wallace did not create the Big Work as a commercial pursuit, or even as articles of his own hand, but as records of a practice not intended to yield its full rewards in this lifetime. Recall the alchemic child floating in the bardo, electrified with enlightenment, and speaking of reincarnation. The cosmos promises eternal return for consciousness, if only we assimilate its truths. “Learn this: that rhythmic rays of human thought enmesh a million inhabited globes—a sentient web.”

- The frontispiece drawing implies that Wallace intended the body of work to ultimately exist as a book, recalling Hildegard von Bingen’s folio Scivias (1152), which illuminated the Benedictine polymath’s divine visions.

- A deeper assessment of the changing ways in which esoteric art is presently being historicized and created can be found in Amy Hale’s recent essay “Communist witches and cyborg magic: the emergence of queer, feminist, esoteric futurism,” for Burlington Contemporary, June 2022.

- https://www.morbidanatomy.org/events-tickets/grant-wallace-symposium