LEOPOLD STROBL: VIEWS

The Austrian artist Leopold Strobl has a straightforward way of working: he looks through the pictures in daily newspapers, selects a scene, cuts it out, mounts it on thicker paper, and then covers much of the surface in colored pencil and graphite. The resulting works are small and share a specificity toward color—not necessarily one repeated cast across each picture, but a collection of hues that is recognizably Strobl’s, much like the telltale palettes of different film stocks. You can tell the simple facts of Strobl’s process just by looking at his pictures, and that is all he wants to reveal. His dark interventions, pressed into the paper in bands, flex and grow like muscles or tumors across the picture plane.

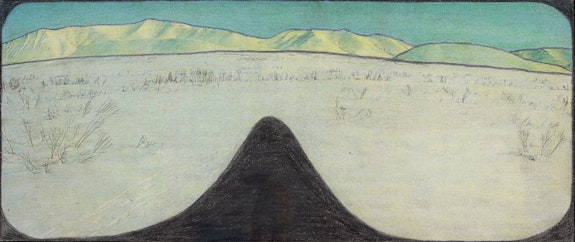

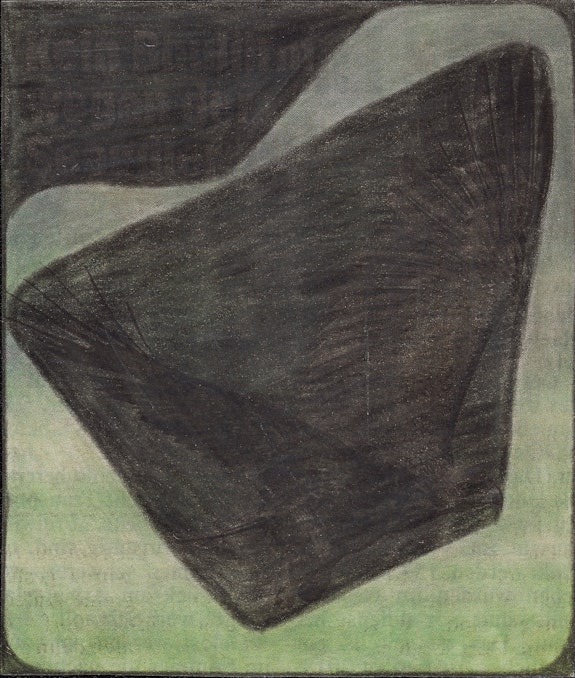

Those blooms of graphite conceal elements of the underlying photograph and guide our eyes toward other, less defined portions of the newsprint. In one drawing (all works untitled), the bottom half of a street scene and all of its pedestrian activity is obscured by sweeping pencil marks rising to a soft peak, leaving only a few hazy buildings above. In another, Strobl covers a group portrait with a bumpy ridge, which rests below fuzzy tree limbs. There is a different variation, where Strobl’s interventions float in the picture plane independent of their rounded borders: an elk covered in a trapezoid or a vehicle on a road subsumed into some cartoonish tongue poking out at us.

Because of the way Strobl bends his forms around the corners of the paper and the central subjects of the pictures, the area left untouched by graphite often resembles a viewport, or some idea of how human perception would look if we could step back behind our own vision. In some drawings, that double ellipse is bent into perspective, suggesting a pair of glasses on a face. In one desert scene, there is the distinct feeling that the viewer is inside a pair of goggles, looking out on the curvature of Earth. Strobl’s marks have such weight because they carry the sense that, in each looping perfection of a shape, they are redefining the world upon which they are placed.

What is the word for this mood that spreads across the pictures, this collection of colors that describes something between history and science fiction? It is a jaundice that conjures no disease, closer to the greenish-yellow root galbinus, which is a bit more round and forgiving in the mouth; or even the woodsy chartreuse, which is far more slick than Cartusianus, the Alpine monks who make that focusing elixir out of so many unknown herbs. Strobl’s colors and shapes are alien enough as to make us pay attention to how words, conjured but unspoken, form in the hollows of the mouth. I’m reminded of how Émile Zola styled the surname of his vicious protagonist Thérèse—who drowns her cousin-cum-husband—as “Raquin,” so close to the French requin, shark.

What Strobl accomplishes depends entirely on the feeling of his drawings, the way vision equates texture with touch and bridges the senses. We can see what those pulpy areas of newsprint and those skids of graphite must feel like under fingers. We attempt to name them and stutter because some shapes require words that are jagged and others require words that are round and self-encompassing. It is humbling, for pencil marks on news clippings to carry such a potency.

In one of Strobl’s drawings from 2020, a central shape bumps up against a curved shoulder, full of radial marks and lateral lines filling in the gaps. Leaning in closer, the whims of Strobl’s wrist yield to an image of a raptor mid-flight, its feathers faintly visible beneath the graphite. It is more than a bird redacted from the newspaper. There is a muscle memory in that specific pattern, a way of coloring-in that most of us forget after grade school. I want to say these things that my eyes tell my fingertips to feel. There is a form cocooning antlers in grass, a lepidopteran spread against church walls. There is form I have yet to name, gathering on the tongue, tasting of metal.