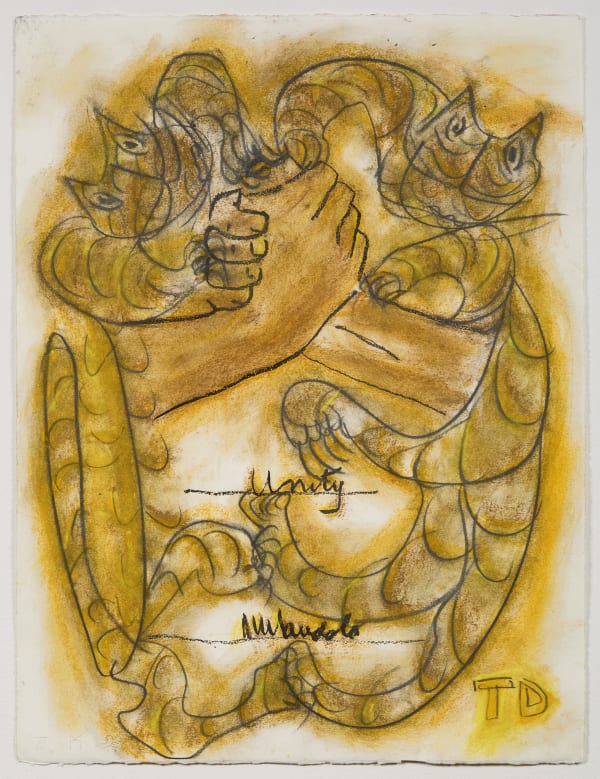

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to present a suite of Nelson Mandela’s Struggle Series lithographs, enhanced with extensive original artwork by Thornton Dial. These lithographs are the basis for The Nelson Mandela Unity Series, a collaboration between Mandela and select international artists.

In 2002, South African artist Marlene Dumas asked Nelson Mandela if she could collaborate on a set of lithographs based on six of his works—in which he depicted his remarkable life through the symbolism of hands. Dumas completed her work in early 2003, and the project subsequently invited other prominent artists to participate, allowing them to portray Mandela’s story in their own unique styles. Participating artists included Tan Swie Hian, Willie Bester, Esther Mahlangu, Nancy Noel, Charlie Mackesy, and Thornton Dial.

Madela’s liaison met Dial in Atlanta and gave him a set of lithographs. Two weeks later, Dial delivered the finished works, stating that this was his first and only collaboration, and that it was an honor to have worked on it. Upon viewing the pieces, Mandela remarked: “these could hang in any direction, it’s a pity my input spoils the effect!”

In 2007, Marlene Dumas’s set sold to a private collection for $750,000. In 2016, Tan Swie Hian’s works sold at auction for $450,000. This year, Nancy Noel’s works will be acquired by a museum in Minneapolis for $130,000.

Dial’s works were first shown at a Nelson Mandela Art Show in Sandton Johannesburg South Africa. The World Economic Forum then exhibited the full collection in 2004.

Photograph of the artist by Jerry Siegel

-

All works:

2003. Pastel, charcoal, and graphite on lithographed print. 26 x 19 3/4 in. (66 x 50.2 cm)Available as a suite in six parts -

Thornton Dial (1928–2016)

Thornton Dial Sr. was born in Luther Elliot’s plantation in Emelle, Alabama. Poverty stricken and deprived of toys, as children Dial and his siblings constructed their own playthings out of found objects—a habit that later influenced his sculptural work. From a very early age Dial was put to work picking cotton; he did not attend school enough to become fully literate. He later worked as a farmer and at all kinds of heavy labor (cement and iron pouring, bricklaying, pipe fitting, carpentry, house painting), as well as iron and steel metalwork for the Pullman Standard Company, where he was employed for close to thirty years. During this time, Dial got married and had four children, and after retiring at age fifty-five he devoted himself exclusively to art. In the decades that followed, Dial created a power-ful oeuvre that recounts the brutal history of the African American experience, the shameful stain of the Jim Crow era, the nascent civil rights movement, and race and gender relations against a backdrop of conflict and democratic ideals.

Dial created paintings, assemblages, sculptures, and drawings. His three-dimensional work is notable for combining everyday objects and their different textures and volumes with his painter’s sensibility for color. “I only want materials that have been used by people, the works of the United States, that have did people some good but once they got the service out of them they throwed them away,” he has explained. “There’s some kind of things I always liked to make stuff with. I’m talking about tin, steel, copper, and aluminum, and also old wood, carpet, rope, old clothes, sand, rocks, wire, screen, toys, tree limbs, and roots. You could say, ‘If Dial see it, he know what to do with it.’ ” In his works on paper, which he began making after a critic wrote that he could not draw, Dial focuses mainly on the subject of women and erotic interactions between male and female figures. The fluid, expressive quality of these works, considered alongside the ornate flamboyance of his three--dimensional works, results in an interesting equilibrium. The winding lines, fragmented shapes, and lucid pigment smears in Dial’s drawings demonstrate the instinctive drive behind his art practice at large—or, as he put it, the struggle to make something beautiful with one’s own hands. Beauty for Dial is, however, tinged with darkness, trapped in the complexities of social history and never cleanly figurative or abstract.

Dial was discovered in the 1980s by William Arnett, a writer, curator, and art collector from Atlanta focused on self-taught and folk art by southern artists. Since then, Dial’s work has been acquired by many museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which in 2018 mounted the exhibition History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift, titled after a work by Dial; the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York); the American Folk Art Museum (New York); the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (both in Washington, D.C.); the High Museum of Art (Atlanta); the Milwaukee Art Museum; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston); the Indianapolis Museum; and the Birmingham Museum of Art (Alabama).