Every winter, the pressure to “be festive” arrives right on schedule. Ricco/Maresca has never been especially adept at seasonal costume changes, but we’re very good at curating objects that refuse to behave like décor.

Presented here is a small constellation of works that lend themselves to being lived with—and, occasionally, gifted. It ranges across decades and purposes: paintings that tilt familiar icons off their axis; figures and fragments that once belonged to architecture, advertising, or domestic ritual; objects whose original function is now half-remembered but whose presence is undeniable. Some works are talismanic, others slyly humorous; many hover between the familiar and the enchanted.

If there’s a spirit tying everything together, it lives somewhere between spectacle and intimacy. Some works announce themselves with some drama; others are quieter, meant to be discovered up close. These are works that can sit on a table, keep watch from a wall, anchor a shelf, or mark a threshold. They invite handling, double-takes, private jokes, and long-term companionship.

Think of it as a cabinet of possibilities for anyone who suspects that the most interesting things are the ones that refuse to sit neatly in a category.

-

-

Ventriloquist Head, American, mid-to late 19th centuryCarved and painted wood with horse hair10 x 4 x 6 in (25.4 x 10.2 x 15.2 cm)(ArU 475)$ 5,000

Ventriloquist Head, American, mid-to late 19th centuryCarved and painted wood with horse hair10 x 4 x 6 in (25.4 x 10.2 x 15.2 cm)(ArU 475)$ 5,000•••

Radiating an otherworldly energy, this raw creation of the American folk imagination mesmerizes with its eerie presence. Its patinated wood and hauntingly rough-hewn features evoke a primal, almost shamanic energy. The mechanical mouth feels both inviting and unsettling, as if it might unleash a voice beyond time. The shock of horsehair, cascading in an unruly mane suggests life caught between the natural and the supernatural. This isn't just a functional object; it's an existential dialogue—crafted by anonymous hands yet charged with personality, humor, and perhaps a touch of menace. It's as if the soul of the carver whispers secrets through it, forever performing.

-

Architectural Owl Form, ca. 1930-40Sheet iron (custom wall mount)16 x 8 1/2 x 1/2 in. (40.6 x 21.6 x 1.3 cm)(ArU 509)SOLD

Architectural Owl Form, ca. 1930-40Sheet iron (custom wall mount)16 x 8 1/2 x 1/2 in. (40.6 x 21.6 x 1.3 cm)(ArU 509)SOLD•••

Cut from a single plate of sheet iron, this stylized owl feels at once like an emblem and a guardian. Its form is reduced to a few decisive cuts—the wide ears, almond body, and incised wings—so that the entire creature hovers somewhere between hieroglyph and street sign. The punched eyes and beak carve out a calm, almost quizzical expression, an alert stillness that suggests it once watched over a doorway, cornice, or threshold. Time has worked its way across the surface, leaving a rich, weathered patina that deepens the sense of quiet authority. Stripped of its original architectural context, the piece now reads as a compact, self-contained presence: part sentinel, part symbol, and an unmistakable character in its own right.

-

Stylized Draped Nude, ca. 1940-50Fired clay with polychrome11 x 5 1/2 x 5 1/2 in. (27.9 x 14 x 14 cm)(ArU 504)$ 2,000

Stylized Draped Nude, ca. 1940-50Fired clay with polychrome11 x 5 1/2 x 5 1/2 in. (27.9 x 14 x 14 cm)(ArU 504)$ 2,000•••

This standing figure feels both vulnerable and utterly self-possessed. Carved in broad, simple planes, her body is presented frontally, with a calm, direct gaze that quietly disarms the viewer. The vivid red drapery pools at her feet and parts just enough to frame, rather than conceal, her nudity—more stage curtain than modesty veil. Speckled flesh tones and the slightly stylized face give her the presence of a devotional statue that has wandered into a more secular, intimate realm. There is a touch of burlesque in the pose, but the overall effect is less about spectacle than about a woman holding her own space: solid, grounded, and unexpectedly tender in her awkward grace.

-

Gus WilsonEider Decoy Head, ca. 1910-15Wood with polychrome (custom base)5 x 6 1/2 x 2 in. (12.7 x 16.5 x 5.1 cm)(GuW 1)$ 7,000

Gus WilsonEider Decoy Head, ca. 1910-15Wood with polychrome (custom base)5 x 6 1/2 x 2 in. (12.7 x 16.5 x 5.1 cm)(GuW 1)$ 7,000•••

Augustus Aaron “Gus” Wilson (1864–1950), the famed Maine carver and lighthouse keeper, had a gift for turning wildfowl into pure, economical form. This decoy head shows him working at his most distilled: the bird reduced to a single sweeping arc, head tucked, and beak folded back along the curve of the neck. The muted paint and timeworn surface read less as hard use than as an object that stayed behind while others went to work on the water. An exquisite sculpture: a compact, modern-feeling meditation on a resting body, all momentum gathered into one quiet, tender gesture.

-

-

-

Portrait of a New England Young Lady, 1860-65Oil on canvas mounted on wood15 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. (39.4 x 33.7 cm)(ArU 529)$ 8,000

Portrait of a New England Young Lady, 1860-65Oil on canvas mounted on wood15 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. (39.4 x 33.7 cm)(ArU 529)$ 8,000•••

The sitter here is a girl on the threshold of adolescence—hair parted and drawn back in careful curls, shoulders bare above a plain dark dress, her face emerging from a field of near-black. The composition is stripped of props or setting, so everything concentrates in the oval of her features and that unwavering, slightly wondering gaze. The artist lingers on the soft planes around the eyes and mouth, giving her a delicacy that’s less about prettiness than about watchfulness, as if she were trying to hold still long enough to be taken seriously. What might once have been a family likeness now reads as something more intimate: a quiet, frontal encounter with a young person caught between worlds, rendered with unshowy but palpable tenderness.

-

George W. BarnesUntitled (Green Mona Lisa), 1963Oil on canvas30 x 20 in. (76.2 x 50.8 cm)(GB2)SOLD

George W. BarnesUntitled (Green Mona Lisa), 1963Oil on canvas30 x 20 in. (76.2 x 50.8 cm)(GB2)SOLD•••

Barnes’s Mona Lisa takes one of the most reproduced faces in art history and pushes it into a different register. The artist reimagines da Vinci’s iconic sitter as an eerie emerald apparition—her expression still serene, but her skin and surroundings bathed in an otherworldly radioactive glow. The original structure is still unmistakable—the folded hands, the three-quarter pose, the winding road and distant crags—but the familiar has become preternatural, as if the image had passed through a chemical or cinematic filter and emerged altered yet strangely intact. The yellowed sky and shadowed landscape feel more like a fever dream than an Italian vista, as though the whole scene were lit from within by some uncanny interior light. Barnes signs and dates the canvas in the corner, quietly claiming ownership of this altered icon—a vernacular Mona Lisa who has wandered out of the museum and into a more psychological, hallucinatory space, bringing her enigmatic smile along for the ride.

-

Erotic Doorbell, ca. 1950Cast bronze with original doorbell hardware8 1/4 x 6 x 1 3/4 in. (21 x 15.2 x 4.4 cm)(ArU 532)SOLD

Erotic Doorbell, ca. 1950Cast bronze with original doorbell hardware8 1/4 x 6 x 1 3/4 in. (21 x 15.2 x 4.4 cm)(ArU 532)SOLD•••

Beyond its exquisite form and richly patinated surface, this object stages a sharp juxtaposition between the public and the private. On one hand, it makes a bold architectural statement—its substantial 14-pound weight and commanding silhouette speak to a deliberately assertive presence in a room. On the other hand, it conceals a secret: to ring the bell, one must discreetly press the right nipple. This hidden mechanism suggests the piece may have once belonged to an exclusive club or an eccentric private residence, where humor, sensuality, and secrecy were not only permitted but quietly engineered into the everyday ritual of arrival.

-

Advertising Countertop Golden Form (Sapolin Paint), ca. 1910-20Gilded aggregate with original glass dome, wood base, and paper label7 1/2 x 7 in. (19.1 x 17.8 cm)(ArU 514)$ 3,000

Advertising Countertop Golden Form (Sapolin Paint), ca. 1910-20Gilded aggregate with original glass dome, wood base, and paper label7 1/2 x 7 in. (19.1 x 17.8 cm)(ArU 514)$ 3,000•••

Under its glass dome, this gold, molten-looking form sits somewhere between specimen and sculpture. Its folds suggest a crumpled cloth, a geological nugget, even a brain—an object that resists being pinned down to a single identity. Whatever its original purpose, the decision to isolate it on a pedestal and seal it beneath glass effectively turns it into a ready-made: a found object elevated by framing, very much in the spirit of the early 20th-century objet trouvé. The black base recalls Victorian display culture—domes used for clocks, taxidermy, devotional miniatures—while the gleaming mass inside feels oddly contemporary, like a small, private monument to compressed matter. It’s a clear demonstration of how context and presentation can transform an anonymous thing into a charged presence, inviting us to project meanings onto a form that refuses to explain itself.

-

![Sugar Bowl, late 18th century Turned lignum vitae with original finish 7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm) [height x diameter] (ArU 489) $ 5,000 ••• Turned with elegant precision, each curve in this sugar bowl flows seamlessly into the next to form a symphony in lignum vitae—a dense, almost indestructible wood prized for its rich color and natural oils that deepen over time. The design is leagues ahead of its time: a near-perfect sphere balanced on a turned base that subtly elevates it, giving it an inconspicuous sense of dignity that reflects the attention and care surrounding sugar’s role in daily life. The original finish has the soft sheen of age, imbuing the wood with a richness that speaks to the material's natural beauty. The lid, with its snug fit and small, tear-shaped finial, is as meticulously crafted as the body, creating a harmonious whole. This object possesses a quiet monumentality, yet it feels almost weightless, as if it could float off the surface beneath. It encapsulates both purpose and presence—a work of art hiding in plain sight.](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Sugar Bowl, late 18th centuryTurned lignum vitae with original finish7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm) [height x diameter](ArU 489)

Sugar Bowl, late 18th centuryTurned lignum vitae with original finish7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm) [height x diameter](ArU 489)$ 5,000

•••

Turned with elegant precision, each curve in this sugar bowl flows seamlessly into the next to form a symphony in lignum vitae—a dense, almost indestructible wood prized for its rich color and natural oils that deepen over time. The design is leagues ahead of its time: a near-perfect sphere balanced on a turned base that subtly elevates it, giving it an inconspicuous sense of dignity that reflects the attention and care surrounding sugar’s role in daily life. The original finish has the soft sheen of age, imbuing the wood with a richness that speaks to the material's natural beauty. The lid, with its snug fit and small, tear-shaped finial, is as meticulously crafted as the body, creating a harmonious whole. This object possesses a quiet monumentality, yet it feels almost weightless, as if it could float off the surface beneath. It encapsulates both purpose and presence—a work of art hiding in plain sight.

-

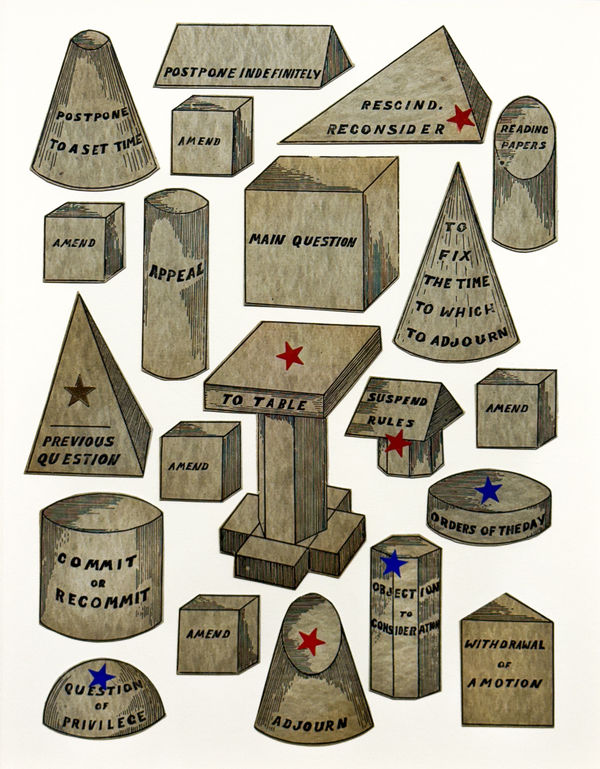

Longan & LonganParliamentary Figures, ca. 1920sCardboard and ink (framed as a group)14 x 11 in. (35.6 x 27.9 cm)(ArU 516)$ 2,500

Longan & LonganParliamentary Figures, ca. 1920sCardboard and ink (framed as a group)14 x 11 in. (35.6 x 27.9 cm)(ArU 516)$ 2,500•••

“Longan’s Parliamentary Figures” appears to be a visual aid or learning device designed to teach the structure and sequence of parliamentary procedure—rules used to conduct meetings and make group decisions, typically based on “Robert’s Rules of Order,” the widely adopted 19th-century manual of parliamentary law by U.S. Army officer Henry Martyn Robert. These cardboard cutouts, found in their original envelope in perfect time-capsule form, represent various motions and procedural elements, helping to make abstract concepts easier to grasp by visualizing their relationships and hierarchy.

-

Carnival Knock Down Figure, late 19th - early 20th centuryCarved and painted wood16 x 5 x 4 in. (40.6 x 12.7 x 10.2 cm)(ArU 494)$ 4,500

Carnival Knock Down Figure, late 19th - early 20th centuryCarved and painted wood16 x 5 x 4 in. (40.6 x 12.7 x 10.2 cm)(ArU 494)$ 4,500•••

Carved from solid wood and painted with rouged cheeks, red lips, and kohl-dark eyes, this anonymous carnival knockdown figure turns a game-piece into a personality. Its bright, theatrical face sits atop a roughly hewn block scarred by age, nails, and impact—evidence of a working life on an amusement midway, where it would have been repeatedly toppled and reset for players’ throws. The contrast between the jaunty, clownlike visage and the battered support gives the piece its charge: a target meant to be hit, yet rendered with surprising care and empathy. Removed from its original context and placed on a stand, it reads less as expendable equipment and more as a small, stubborn survivor of popular entertainment—part sculpture, part collaborator in countless vanished nights of noise, laughter, and competition.

-

![Sugar Bowl, late 18th century Turned lignum vitae with original finish 7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm) [height x diameter] (ArU 489) $ 5,000 ••• Turned with elegant precision, each curve in this sugar bowl flows seamlessly into the next to form a symphony in lignum vitae—a dense, almost indestructible wood prized for its rich color and natural oils that deepen over time. The design is leagues ahead of its time: a near-perfect sphere balanced on a turned base that subtly elevates it, giving it an inconspicuous sense of dignity that reflects the attention and care surrounding sugar’s role in daily life. The original finish has the soft sheen of age, imbuing the wood with a richness that speaks to the material's natural beauty. The lid, with its snug fit and small, tear-shaped finial, is as meticulously crafted as the body, creating a harmonious whole. This object possesses a quiet monumentality, yet it feels almost weightless, as if it could float off the surface beneath. It encapsulates both purpose and presence—a work of art hiding in plain sight.](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-artlogicwebsite0078/usr/exhibitions/images/feature_panels/3063/aru-489.jpg)