George Widener was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1962. Even as a child, he would transform the numbers around him (a license plate, a house number) into dates. This evolved into an intense fascination with calendars, historical events, numerical systems, and the ebb and flow of time. These fixations are heightened, or perhaps caused, by Widener’s Asperger’s syndrome and the inherent lighting calculation, memory, and drawing skills that are associated with it.

Throughout his career, the artist has created distinct bodies of work that represent the depth and versatility of his visual and conceptual toolbox: from his Titanic works and Megalopolises to his Crispr and Pi works, from his Magic Circles and Magic Squares to his Self-Portrait series.

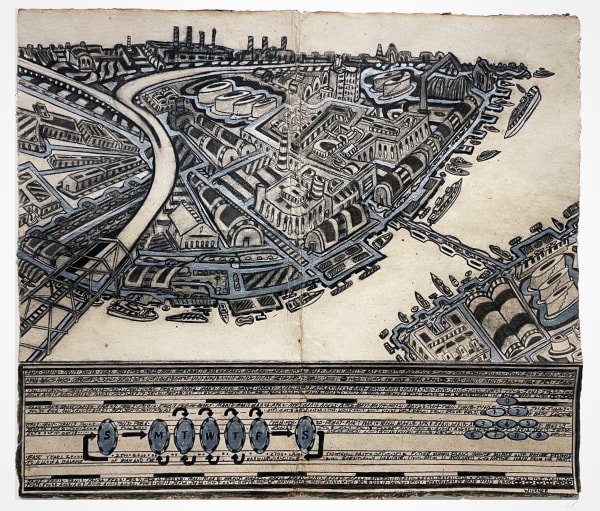

The group of works included in Mindscapes presents a series of expressive vignettes capturing the traffic and chaos of modern cities, which Widener experienced during past travels to Europe and Asia. Using his innate eidetic memory—the ability to recall an image from memory with great precision—Widener conjures these scenes with ink and charcoal, employing densely rendered and overlapping networks of lines. The small format of these drawings allows the artist to work quickly and spontaneously; the recurring date panels at the bottom of each work capture a unique aspect of his interior life (that of a calendar savant), as he counts dates to calm himself down amid the urban turmoil. The picture plane thus encompasses a central dichotomy: the figurative cityscape and the abstract dimension of numbers; the collective buzz of the of the city against the cadence of the artist’s mind.

Widener’s work is in private and museum collections worldwide, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands, the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the abcd/ ART BRUT collection and the Centre Pompidou, both in Paris.

-

"I had visions of futuristic intelligent machines, cities created with symmetry and balance, governed by a calendrical order I discovered in my dreams."

-

"Like fire, this moving about to find the good ahead or leave the bad behind is something deep inside us. Give someone a nice furnished cave with all the accessories and they might just rather trek off into the unknown forest instead. This is what causes our modern-day communal migraines, known as traffic jams. The highways and roads—the arteries and veins of our cities—get clogged up to the point of overload. Yet still we persist."

-

“I would take no part in this jam by instead counting dates that would pop into my mind, so as to keep my nerve (“recite the Mondays of 2000 until the light turns green”). You must not fall down for that is death, as those behind you cannot stop. I learned to swerve and to jump in and out, sometimes your life is literally at stake in the timing. Don’t ever trip and fall."

-

"These things come from a different part of your brain and are subconscious. That’s exactly what I do with numbers and calendar calculating: it is the counterpoint to all my experiences, the part of my brain where I return to when the 'traffic jam' out there becomes too chaotic."

-

"In a nod to Frank Herbert, author of the sci-fi novel Dune, my calculating without numbers becomes a bit like the 'travel without moving' idea. A Guild navigator using an internal GPS… I record the landscape in a multidimensional manner."

-

-

Untitled (Paris Cityscape), ca. 2017Ink and charcoal on paper9 1/4 x 10 in. (23.5 x 25.4 cm.)(GW 219)$3,000

Untitled (Paris Cityscape), ca. 2017Ink and charcoal on paper9 1/4 x 10 in. (23.5 x 25.4 cm.)(GW 219)$3,000 -

Untitled (Boston Interior) , 2020Ink and charcoal on paper10 x 9 1/4 in. (25.4 x 23.5 cm.)(GW 224)$3,000

Untitled (Boston Interior) , 2020Ink and charcoal on paper10 x 9 1/4 in. (25.4 x 23.5 cm.)(GW 224)$3,000 -

Untitled (Boston Interior), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm.)(GW 226)$3,000

Untitled (Boston Interior), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm.)(GW 226)$3,000 -

Untitled (Paris Cityscape), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper11 1/4 x 10 in. (28.6 x 25.4 cm.)(GW 225)$3,000

Untitled (Paris Cityscape), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper11 1/4 x 10 in. (28.6 x 25.4 cm.)(GW 225)$3,000

-

-

"Some people simply get overwhelmed, for various reasons they just can’t go on anymore in the complex infrastructure of cities. Interiors represent these pauses. We’re all trying not get run over, I think."