For over 40 years, Ricco/Maresca Gallery has helped build some of the great private, museum, and corporate collections. We have also come across wonderful works at a lower price point—well below Darger, Traylor, Edmondson, Hawkins, and Ramírez — that have great integrity, and the ability to teach us about looking and collecting. “What’s it worth?” This question is only easy to answer if we look at art as a commodity. That is not what we’re doing here. Modestly priced works can still have important things to say and speak eloquently alongside master works; visionary collectors have been exploring this realm for a long time.

We found Kate Hackman, a dealer who works under the name of Critical Eye Finds, whose eye we admire and who deals with this type of material. We struck up a conversation about looking—how we look, why we look—and about our shared pleasure in finding unexpected things in unexpected places. Ultimately, our dialogue led to the concept of this online viewing room, which we hope will be the first in an ongoing collaboration. This is an experiment, one that we are not approaching from the mindset of commerce. We are interested in exploring the idea of looking at art and objects as independent from the realm of the art market, as only then will we truly understand what they have to say.

With this in mind, we invited Hackman to introduce this project and to consider a group of late 19th-early 20th century drawings by Carlotta M. Huse of Ossipee, New Hampshire and Wayne B. Blouch of Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, which we selected together.

-

A friend recently described the endeavor of searching for objects that speak to us as an act of self-portraiture. He was referring specifically to Critical Eye Finds, through which I have built, and continue to build, an archive of photographs and writing that documents and attempts, in some small way, to honor each thing I have found and offered for sale. But surely the same could be said for all of us who look at, and look for, things; through the ongoing process of seeking and choosing and making room for objects in our lives, we define and reveal ourselves. And, as my friend I think was getting at, this form of self-portraiture may be as true a way to know— perhaps to discover—ourselves as any other. It is also gloriously unfixed, forever in process , as we evolve through looking and finding and looking some more.

-

"A friend recently described the endeavor of searching for objects that speak to us as an act of self-portraiture ... But surely the same could be said for all of us who look at, and look for, things; through the ongoing process of seeking and choosing and making room for objects in our lives, we define and reveal ourselves. "

-

Having spent most of my career in the non-profit arts world supporting the work of emerging artists, I started Critical Eye Finds perhaps most of all as a vehicle for looking at different things, differently—looking through a lens of curiosity rather than hurrying to analyze, judge, situate; searching for things I might not have the language to describe or knowledge to contextualize, but which light my imagination, strike me in the gut, or make my heart ache. Mostly for me these special things are ones made by people unknown to me, some time ago, many anonymous to all of us, now forever. It often feels like some small miracle that they endured to be found at all, and even more miraculous they should arrive in the present provoking intense feelings of recognition, empathy, and often what seems nothing short of pure love.

-

"looking through a lens of curiosity rather than hurrying to analyze, judge, situate; searching for things I might not have the language to describe or knowledge to contextualize, but which light my imagination, strike me in the gut, or make my heart ache."

-

Perhaps especially now, with so much to feel pessimistic about, how heartening and affirming to find, always there, the human compulsion to make things: to make utilitarian objects special, or to make special things largely for their own sake—to pass the time, or to practice skills, to find pleasure, or to try to make some bit of sense of the world and oneself in it. Then also there is the persistent compulsion to gather things, to prize them, to hold them close and hand them down, for any number of reasons, in some cases surely in recognition of their fineness and potential future value, but at least as often for reasons deeply personal. Graciously ushered into the future, they arrive to be found again—hopeful things aspiring to be rescued or retrieved, re-prized, shepherded forward.

-

"Perhaps especially now, with so much to feel pessimistic about, how heartening and affirming to find, always there, the human compulsion to make things: to make utilitarian objects special, or to make special things largely for their own sake—to pass the time, or to practice skills, to find pleasure, or to try to make some bit of sense of the world and oneself in it."

-

So, what might one be looking to find? For me, searching for objects is not unlike searching for lively company—things that have something to say for themselves and surprise at every turn, things that hold knowledge, histories, and mysteries, too, some worn on their surfaces and others that may never be unlocked. They are objects with which one might have a conversation that could unfold slowly, with the richest among them revealing different aspects of themselves over time, including through proximities to other objects. Sometimes the pull is a thing’s sheer beauty, or the exceptional skill and labor invested in its making, transcending time and impossible to ignore. Or it might be its clarity and truthfulness, allowing one to travel as it opens a portal into another time, place, mind, life. Sometimes an object’s transformation over time makes it something now—the wounds that show it was much used, fulfilling a need; the mends that attest to its value to someone, functionally or sentimentally. Other times it’s the shift of context: from past to present, whereby all that has happened in the world since its making has altered the ground upon which it stands, lending newfound relevance and resonance; or from functional object to aesthetic one, now a serendipitously satisfying readymade.

-

"So, what might one be looking to find? For me, searching for objects is not unlike searching for lively company—things that have something to say for themselves and surprise at every turn, things that hold knowledge, histories, and mysteries, too, some worn on their surfaces and others that may never be unlocked."

-

Some schools of arts education would describe projecting one’s own narratives onto an object as a less sophisticated form of looking than analyzing why an artist made certain choices and contextualizing their work within history and art history, but perhaps we could use more unsophisticated looking. And if good design is generally considered that which offers elegant, efficient solutions to a given problem, perhaps the opposite more often makes for interesting objects—those that embody round-about, awkward solutions to problems (or to no problems at all), or which wear on their surfaces a whole string of fixes and adaptations made by different owners or users over time. Here is tenderness, and imperfection, and hands and minds at work together, and, for me at least, where the real stuff of beauty, and life, dwells.

-

"if good design is generally considered that which offers elegant, efficient solutions to a given problem, perhaps the opposite more often makes for interesting objects—those that embody round-about, awkward solutions to problems (or to no problems at all)"

-

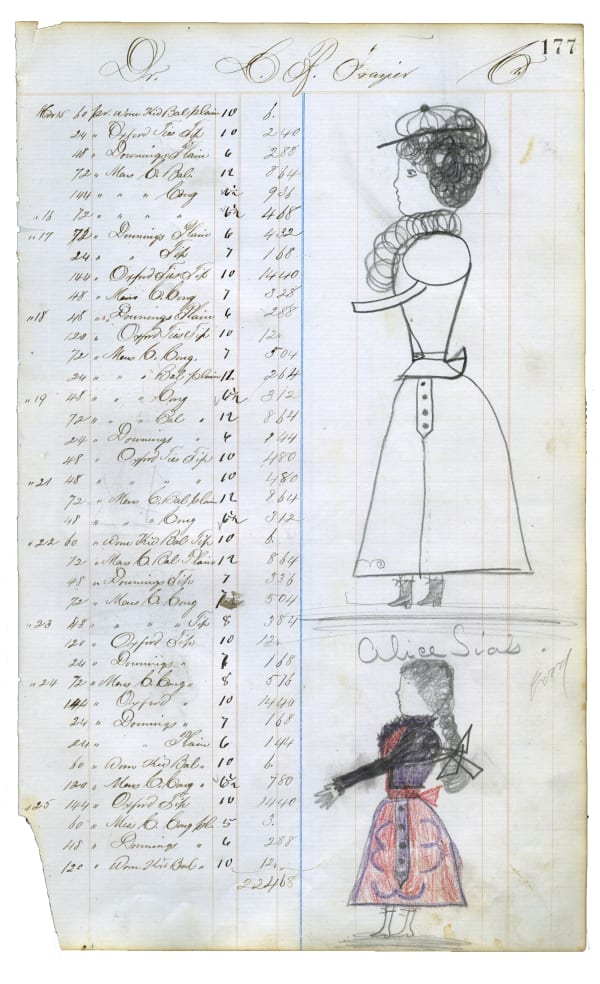

And so, to these drawings—done more than a century ago by two young people we otherwise know little about, but which themselves tell us quite a lot about those makers, their times and environments and interior lives. What we know definitively about Carlotta M. Huse is that her parents kept a small hotel, and when she was about 8 years old, she was given an old hotel ledger, in which she began to draw, over and around the writing already filling many of its pages. Wayne B. Blouch was born in Bunker Hill, Lebanon County, and went on to teach social science in Elizabethtown, Lancaster County, until his death at the age of 55. A few of these drawings are dated 1910, so were made when he was about 10 years old, suggesting that he was quite a prodigious young artist.

-

"What we know definitively about Carlotta M. Huse is that her parents kept a small hotel, and when she was about 8 years old, she was given an old hotel ledger, in which she began to draw ... Wayne B. Blouch was born in Bunker Hill, Lebanon County, ... A few of these drawings are dated 1910, so were made when he was about 10 years old, suggesting that he was quite a prodigious young artist."

-

Found in all of them is wonderful specificity; one can viscerally feel these young artists’ pleasure in recording the particular details of their particular subjects. Blouch draws every bell and whistle on a train engine, every tool in a farrier’s shop, not missing the chamber pot under the bed of a couple in their nightdresses. Huse, clearly fascinated with the fashions of the day, exuberantly documents hats and hairstyles, dresses and bows and boots, colorful patterns and corseted silhouettes. She also painstakingly maps rooms (of the hotel where she lived, we assume) as if seeing through the walls, down to every table and chair, often with a sleeping body in the bed, and sometime with a note identifying whose room.

-

"Blouch draws every bell and whistle on a train engine, every tool in a farrier’s shop, not missing the chamber pot under the bed of a couple in their nightdresses. Huse, clearly fascinated with the fashions of the day, exuberantly documents hats and hairstyles, dresses and bows and boots, colorful patterns and corseted silhouettes. She also painstakingly maps rooms ... as if seeing through the walls,"

-

Through their specificity, the drawings capture a sense of place and community, rituals and rhythms, and yield a marvelous feeling of intimacy. It is hard to look at these drawings without picturing Huse and Blouch in proximity to their subjects, ledger or sketchbook in hand. One can imagine Huse, perhaps planted in a corner of the hotel lobby, watching this stream of women, and an occasional exotic other, come and go, while one has the sense that the subjects of Blouch’s drawings—from the squirrels gnawing away on ears of corn to the man pushing his mower—were friends and fixtures in his small town, rendered larger than life through his attention. The drawings also bring us straight into minds of the two makers. One can feel Huse tracking though each room of the hotel in her head, making sure she has accounted for each one, or imagining herself a bit older, thinking about which hat she would choose for herself. Through Blouch’s drawings we are granted access not just to his immediate world but to a fantasy realm, in which a dog might read the newspaper, or a boy might fly a giant bird like a kite.

-

"Through their specificity, the drawings capture a sense of place and community, rituals and rhythms, and yield a marvelous feeling of intimacy. It is hard to look at these drawings without picturing Huse and Blouch in proximity to their subjects, ledger or sketchbook in hand."

-

The feeling of intimacy the drawings provoke is, too, a product of our access through them to the process of these two young artists figuring out how to draw—making choices about what and how, and displaying inventiveness as they do. Over the course of Huse’s ledger, from which these drawings are but a selection, we see her grip on her pencil, or crayon as it may be, become stronger and more assured. Almost throughout she responds directly to the gridded and partially filled pages of the ledger she inherited, typically using the blue vertical center line as a border, then creating her own grids on top of grids, often seemingly reflecting hierarchies of size or age, i.e. grown women get larger cells than little girls, and little girls larger ones than animals! Through this method she takes advantage of most every blank inch of the page, though she sometimes opts, perhaps in absence of any more room, to draw over existing writing too. Several of Blouch’s drawings are done on ledger paper as well, where he uses page’s horizontality to create drawings feeling almost panoramic in scope. Even at his young age he makes some use of perspective, as in a wonderful sequence of five eyes and ten ears in a staggered row of horses, but then he forgoes it elsewhere, seemingly in favor of accounting for every single nail on the train tracks, for example.

One might hope Carlotta Huse and Wayne Blouch would have recognized each other as kindred sorts had their paths crossed during their lifetimes. Surely they never did, but in the wonderous realm of objects they meet now, like distant friends who’ve travelled far to find one another, and us, too… what luck, and what a thing.

-

"One might hope Carlotta Huse and Wayne Blouch would have recognized each other as kindred sorts had their paths crossed during their lifetimes. Surely they never did, but in the wonderous realm of objects they meet now, like distant friends who’ve travelled far to find one another, and us, too… what luck, and what a thing."

-

To see all these works on Critical Eye Finds click here