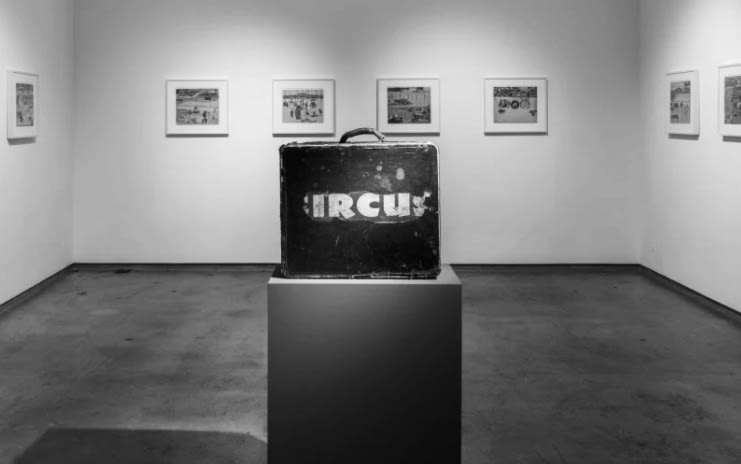

The only known beginning of C. T. McClusky’s story dates back to a Sunday morning in 1975 when a middle-aged woman named Corine set up a booth at the Penny Flea Market Island Drive in Alameda, California. A battered old suitcase glued to a large, worn-out paper cutout of the word CIRCUS stood there silently shouting out its name amid the bric-à-brac, and it caught the attention of John Turner—then a volunteer curator at the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco. With just one brief look at the suitcase’s contents, he realized he had “stumbled upon a treasure.” It was relayed to Turner that McClusky was a circus clown who lived during the winter seasons between the late 1940s and mid 1950s in an Oakland boarding house run by Corine’s mother. He kept few personal belongings there other than a stack of Life magazines and newspapers; he occupied his time off the road creating mixed-media collages that resurrected the circus in its absence and on occasion, Corine recalled, would present a work to her or one of her playmates.

If McClusky was born around the turn from the 19th to the 20th century, as a youth he was right in the middle of the second Industrial Revolution’s avalanche of new technology following the first transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. New inventions included the telegraph, the phonograph, the incandescent lightbulb, telephone, radio, motion pictures, automobiles, aircrafts, and television. The rise of mass marketing and consumer culture in postwar America brought a proliferation of imagery of this new world across print media. McClusky appropriated and repurposed pieces of this graphic excess into his mental geography—materializing again and again in his collages—and in doing so he found a formal and spiritual outlet that paralleled Surrealism’s best efforts to free the unconscious mind from creative restraints. McClusky’s collage milieux engage in all manner of interesting visual discrepancies: photography converges with caricature; black-and-white with Technicolor; naturalism with hyperbole; perspective and proportion are thoroughly out of synch. As John Turner points out,* the artist subscribes to a kind of hieratic visual logic, indicating importance by size and not necessarily by placement—so we see a cheetah that could match King Kong, or a ringmaster towering over the big top, almost audibly summoning us with his trumpet.

Adding to this representational pastiche, the artist’s circus landscapes include a junction of signifiers from different settings and time periods. The crowd around the big top includes fashionable people dressed in business or casual attire, men in factory-work clothing, suburban families and urban loners, mounted cowboys in hats and neckerchiefs, Plains Indians in feathered headdress. McClusky’s fixation with modes of transportation mirrors that of a collector: passenger and freight trains (steam engines, diesel, and electric locomotives), airplanes, automobiles, trucks, buses, trolleys, trailers, motorcycles; even prairie schooners make an appearance around his circus. His particular insistence on trains and airplanes suggests a sense of connectivity—to an expanse outside the picture—but also estrangement and dislocation, especially when they travel at unstable or illogical angles.