I’m sitting here at Starbucks on Auhai Street in Honolulu, waiting for what might be the first interview ever with Rosie Camanga—certainly the first one since his death–and I can’t help but compare the impeccably manicured environment I find myself in, to what was the pleasure-intense, magnificently licentious, culturally raucous, and violence-ready street life of this neighborhood when Rosie arrived.

By best accounts, Rosie showed up in Honolulu from the Philippines “sometime prior to World War II.” My source is none other than Don Ed Hardy, who wrote a richly personal essay for the first Rosie show at Ricco/Maresca three years ago. In that piece he described Rosie as a “tough-minded” figure who “survived for decades in control of his own game in a volatile honky-tonk environment.”

That portrait rendered Rosie instantly recognizable when he walked in. His well-insulated, witnessed-it-all quality—stratigraphically constructed—was charmingly unsuited for today’s Honolulu.

I shook his hand, we sat down, and he declined a beverage. I think that if I offered him an oat-milk cappuccino he would have instantly bolted (or perhaps turned it into a flash art design).

Rosie Camanga Untitled, 1950-1960

AH: I have a sense you don’t like small talk, so should we get right to our interview?

RC: Where’d you get that idea? I must have tattooed thousands of people in my life, and most of them required conversation. They were nervous, insecure kids. I was a kind of shrink with a needle.

AH: Interesting that you say “nervous and insecure.” In 1944, Honolulu was teeming with GIs on leave, many of whom were emotionally prepping for a possible invasion of Japan.

RC: It would have been a death sentence for thousands.

AH: From today’s perspective, it’s easy to forget the emotional state of those sitting in your chair, and just focus on the art. I was doing some research for our interview and came across a review of Homeward Bound: The Life and Times of Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry. It described the sailors as “miles from home and ready for war” and that they “found solace in the bars and tattoo shops.” Sound familiar?

RC: They had to act tough and find a way to feel tough. Tattoos helped. It was a form of recreation, rebellion, and resistance. But they were scared shitless. It was what you would now call an existential moment. Having a drink and choosing their personal tattoo was just about all the freedom they had

AH: A urban slang emerged that called the process “screwed, stewed and tattooed.”

RC: Never heard it.

{I guess that’s what Don Ed Hardy meant by Rosie’s “sly” sense of humor}

Rosie Camanga, Untitled, 1960-1980

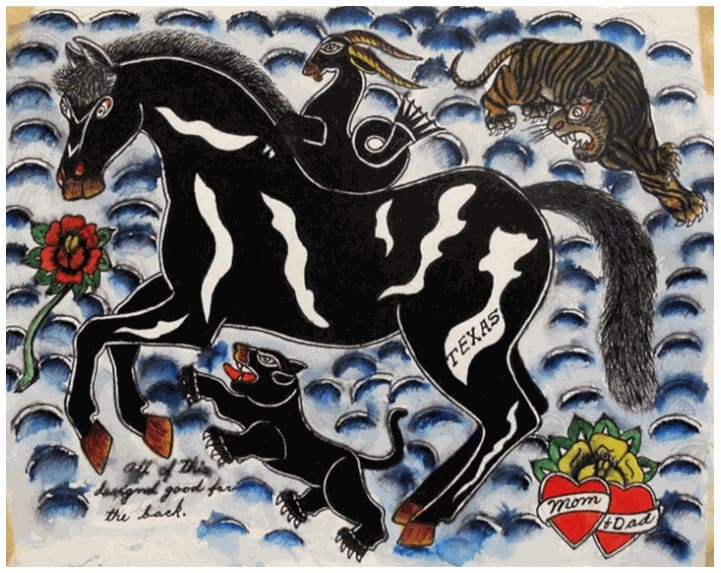

AH: When I look at your drawings, I can see some of the valences you described, and how you addressed them. Some of your images are steeped in home and nostalgia, like a chipper Mickey Mouse, or “Mom + Dad” ribboned against a pair of hearts and a rose. Or what I found to be a strikingly odd image of two small bears holding a vase, with a caption that declares “I love my garden flowers.” These all look backwards to a safer if not saccharine time. Then there are images that speak to a violent future—animals fighting, viciously threatening serpents. Some are erotic, but in a wearable kind of way. Did different kinds of men choose different designs?

RC: You sure trotted out some fancy words there.

AH: To restate: how did the guys decide?

RC: It was all about how they felt in the moment. If they just wrote a letter home—or one just came in—they were more likely to go for the mushy “I love my family” stuff. If they were focused on getting shipped out, or were hanging out with their friends, talking about finishing the war and feeling tough, they would choose something to pump them up. Or they would choose a Japanese girl, a geisha type. It was their way of saying that they’re on the way to Tokyo.

Rosie Camanga, Untitled, 1950-1960

AH: I hadn’t thought of that before… Your work interrogates the full range of human emotions. There’s the testosterone surge of a warrior slaying a dragon and the witty fatalism of a snake wrapped around a grinning skull. Simultaneously, your imagery offers peacocks and roses and religious scenes with images of the Virgin Mary protecting sailors. And then there are designs that capture the local, transitory moments in Hawaii. I was struck by an entire sheet dedicated to a bemused man-in-the-moon face. Below it, the inscription reads “Hawaiian Paradise”, and a caption that proclaims “I am in the moon.” And lots and lots of mermaids. Do you remember that one?

RC: Oh yeah. I came back to the shop one night and a full moon was hanging in the sky. It was beautiful. But at the same time, Hawaii wasn’t exactly a paradise then. Compared to where the boys were headed, though, it might have become one in retrospect.

AH: So the image is ironic?

RC: You could say that.

AH: You only get a tattoo once, but its meaning changes as you get older. That’s true of looking at any kind of art, the in-the-moment interpretation depends on where you are in the river of life. So tell me, how did you decide what to draw and how to arrange it on an individual sheet of paper?

RC: I gave it a lot of thought, and I gave it almost no thought, if you know what I mean. Like the “Man in the Moon” that just arrived in my head. There were dozens and dozens of tattoo parlors back then, so I had to stand out. I drew things that I knew would sell, because they were popular in the places I worked before I went off on my own. I saw what was selling and then I created illustrations to help me stand out.

Rosie Camanga, Untitled (You ripe, eat it), ca. 1950

Rosie Camanga, Untitled, 1950-1960

AH: That certainly shows in your work. It’s a mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar. What do you think of the idea that you were doing two-sided marketing? The illustrations sold your skills. On one image you wrote “All of this designed good for the back.”

RC: How helpful of me.

AH: And at the same time, once you tattoo someone, it becomes a permanent part of who they are and will be. Their personal brand, as we would describe it now.

RC: True enough. Anyone who gets tattooed is going to carry that thing with them for the rest of their lives. So I expressed myself, and gave them ways to express themselves. If they wanted something obvious, I offered it. If they wanted something more intriguing and mysterious, it was right there on the wall, too.

AH: In Don Ed Hardy’s introduction to Ricco/Maresca’s first exhibit of your work, he compared you to Sailor Jerry, who of course is a tattoo legend. Hardy wrote that Jerry “realized Rosie’s tattoo ability was primitive, to put it mildly, but I respected him for his sobriety and industriousness.” I wouldn’t describe your work as primitive. Can’t comment on your sobriety…

RC: Did he say that? I am going to have to talk to him about that.

AH: When I compare your work to Sailor Jerry’s, I find his tattoos to be more precise, crisper and more defined, but also less emotionally complex and nuanced. Your work is softer and invites the imagination in. There’s a wonderful weirdness. But even your images that are more typical of tattoo art have a distinctive Rosie touch.

RC: I appreciate that, but that was not intentional. I just created tattoos that I liked and I hoped others would like.

AH: Do you remember a pin-up image of a vaguely Asian woman (hard to tell if you meant her to be Japanese or Hawaiian given how the cultures collided) who has a delicate set of wings and, of all things. an ice-cream cone on her head?

RC: I probably created thousands of images. That may have been an inside joke. On myself. I was responding to what I heard and what I saw—on the streets, in magazines, in my nightmares. I worried about what was going to happen to all those brave young guys who opened themselves to me.

Rosie Camanga, Untitled (Hot Stuff Pinup), ca. 1950

Rosie Camanga, Untitled, 1950-1960

AH: You must have had many customers from Texas in your shop. I’ve seen, for example, a rope pattern incorporating a prayerful bull (he has a cross on his forehead), spectacular testicles, and an ironic “Great Bull from Teaxas” as the caption.

RC: Are you making fun of my spelling? After more than 50 years, how about the decency of spellcheck? But yes, lots of Texas boys wanted an image of home, or at least how Rosie saw home.

AH: I can’t let you go before I ask about one image. Ricco/Maresca calls it “Devil and Consort.” It’s a frontal image of a devil, horns and all, wearing one earring (very au courant) A naked woman, seen from the rear, is perched on the devil’s outstretched tongue. Two fang-like teeth straddle his tongue and push up against her thighs. She is wearing red stiletto heels. He is wearing a matching red bowtie and lightning bolts frame the image.

RC: As I recall I only sold one of those. I fantasize that it ended up as an indelible imprint on some guy who went home and hid it for the rest of his life. He may have joined the clergy as recompense.

AH: The image is formalistically brilliant. What were you thinking? RC: The devil lies inside all of us, so why not have him outside us? I had never seen a tattoo like that, for obvious reasons. It takes courage to display the truth. More courage to display it than to draw it.

AH: Last question. How do you think the guys felt when they left?

RC: One guy looked at his arm and said to me: “thanks, Rosie. No one can hurt me now.”

{And with that, Rosie stood up and left}

*Adam Hanft is a widely-published cultural critic; co-author of “Dictionary of the Future;” a passionate follower of Outsider art; and friend of the pioneer class at Ricco/Maresca.

Rosie Camanga, Untitled, 1950-1960