The subject of my work is that of time and, more precisely, the shifting and symmetry of time—which I believe occupy every individual’s subconscious. This theme has developed and transformed in my drawings since 1985—the year I began keeping notebook records of numbers that appeared in my dreams. I believe that I have a genetic predisposition to be fascinated with time and drawing. Dates and their mystical properties have interested me since I encountered my grandmother’s calendar in Kentucky in 1968. They are connected to my personal mood and my daily well-being.

I still find it odd and curious somewhat that I am included in a field of Outsider Art—which includes artists with a very private world view—for I feel that I am revealing that which is pluralistic within us all. Today, I’m certainly not an outsider artist, although I may have fit that description in the past (1986 to 1994). Although my investigations and conceptions of time are certainly self-taught and personal, they are not necessarily outside the canon of human experience or destiny. They are indeed juxtaposed adjacent to the future evolution of technology and human neurological development. This is to say that perhaps one day some of my pictures will awaken from their present hibernation, or, they will not; thus, destined to continue only within my art movement of one (to borrow from John Maizels) whereby I have overshot the scientific possibilities.

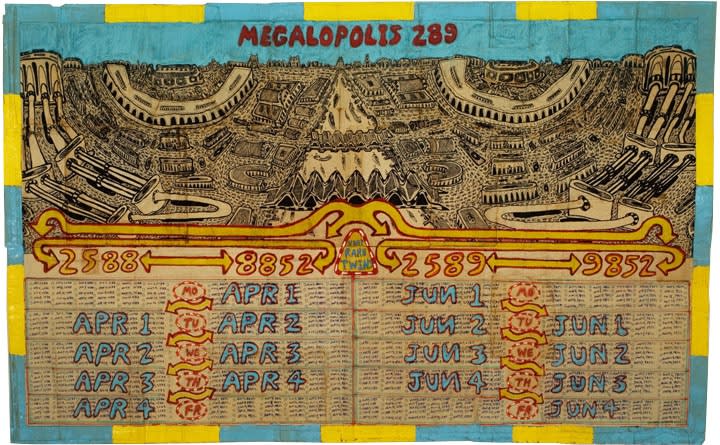

The question here is whether my calendric calculations and reference points are merely personal or whether they are connected to a futuristic synergized public. I’d offer the suggestion I might be an outsider mathematician of sorts who has found refuge in making art. Examples of my work I’d cite are my ‘Magic Time’ squares (time element hybrid matrices in math lingo), symmetrical time based Megalopolis cityscapes, lists and disaster works. These pictures came to me in dreams, which is kind of how mathematicians arrive at solutions as well.

This pluralistic world of time first appeared to me as I was oiling gears of a 10-speed bicycle in a shop in Austin, TX in August 1987. That night I went back to the bunkhouse shelter where I was staying and began laying-out the relationships of time-shifts in my notebook. The shifting gears of the bicycle revealed the potential that the gears of time could change as well—it was possible to switch back and forth between connected dates, so to speak. This revelation had in fact concurred with a sudden burst of memory about a dream I had while interred and forcibly drugged at the Austin State mental hospital some months earlier.

Magic Square 12-21-2012 (Conspiracy), 2012, mixed media on paper, 60 x 45 in

In 1986, I had a breakdown of sorts and was throwing garbage cans into traffic. The police came, I fought them and was restrained. Luckily, I was taken to the hospital (not jail) where I was forced into a straitjacket. I was injected for days with unknown drugs. I drifted in and out of consciousness for several days. During this time, I once woke up strapped down on a bed in a darkened room with barred windows. I experienced a great moment of calm and tranquility and it was there I had my first vision of Time as a monolithic crystalline structure where past, present and future coexisted in one space. The combination of these 2 experiences (bike shop and hospital) laid the foundations of what is known as my artwork. That which was previously unseen suddenly became clear to me. Dreams and subconscious images of time would always be proved correct by conscious calculations. I saw time in my subconscious as a geometric form or a crystalized structure. Ever since, my work has attempted to convey these visions.

Magic Square, 2016, mixed media on paper, 50 x 50 in

Although I have been able to see and understand dates since I was a child—as a 7-year-old I could have told you that July 4, 1916 was a Tuesday for example—these subconscious visions were something altogether different. As spokes rotate on a wheel around a central hub, I saw an interactive body, a conjoined system of dates in their pristine form, interlocked together in a dynamic network of fluid time: a lively bringing together of the past, present, and future. The idea was not the outcome of a sum of progressive efforts, but rather it arose suddenly and dramatically. There was an emotion and urgency attached to it, the kind you might experience upon waking up from a vivid colorful dream (whether pleasant or unpleasant). I found myself with a new meaning in life.

I could focus upon my invention with minimum distraction by sleeping in the shelters at night and working at the library during the day. Several years of experimentation further revealed that I could travel the world in simple fashion and enjoy working my idea on an income of less than $2000 a year, which I was easily able to earn through day labor jobs. I began my real wandering around 1988 and have been to more than 70 countries since. I often went to countries with less than a hundred dollars and no one to call. It seemed to somehow always work out although today it seems fool hearty. Sometimes I flew to a new country and decided to just stay in the airport; it’s a good place to work. I flew to London and stayed at Gatwick for ten days, moving around with disguises so as not to be arrested—it was a great vacation.

A few strange and humorous moments occurred in my travels. In 1988, a crazed man in rags, wearing a blanket at a salvation army homeless shelter was watching me draw one day and loudly declared to everyone that I would one day become a “successful” artist, selling my work for thousands of dollars. It was laughable, unthinkable at the time that this would ever occur. Another time, in 1999 in Amsterdam after being hungry and thrown out of a church after asking for food, I became out of desperate necessity an apprentice of sorts to an accomplished Dutch rare maps thief. We would steal the maps and then sell them back to dealers. One night by chance we attempted (unsuccessfully) to break into an art gallery—where years later my drawings would be shown and I was presented as a dignified guest with some fanfare.

Megalopolis 789, 2011, mixed media on paper, 55.24 x 63.75 in

I believe that truths are often revealed in unexpected divergent events, the past and the future are joined in subtle ways. I’ve been interested in disasters as an anthropology project of sorts. The Titanic has featured itself in my work. I have had moments of sights and smells of that ship. I had for some time an acute sense of stress related to small spaces on board during the disaster. It revealed itself to me at brief unexpected moments. Later I was amazed to read of electricians and telegraph operators who ‘stayed on’ until the final moments trying to keep the ship going. As you know, George D Widener of Philadelphia was on that trip and drowned along with his son Harry Elkins Widener. They had been in Europe…. collecting rare maps and books. I draw the Titanic in different ways every time because it has many different stories. The thousands of dates I explore in these pictures are for me a remembrance of a life-time lost in tragedy.

There is a time shape shifting of sorts, a going back and forth, that always exists in my work. I believe that this is not an uncommon experience and that many people have either a past life experience or a subtle remembrance of the unfamiliar. Time travel, different realities, parallel universes seem to be embedded within our human experience. So perhaps, even if the calculations in my drawings are too complex to be understood, the subject matter of my work is embedded within every individual’s subconscious.

To see video of the Post-Dubuffet: Self Taught Art in the Twenty-First Century Symposium, click here.

Megalopolis 2053, 2015, mixed media on paper, 40 x 36 in

Huge Disasters, 2010, mixed media on paper, 54 x 6.5 in

100 Years Titanic, 2012, mixed media on paper, 58.7 x 59.8 in

Titanic 100 Years Anniversary, 2012, mixed media on Chinese rice paper, 26 x 71 in

Renewable, 2016, ink on paper, 41 x 48.5 in