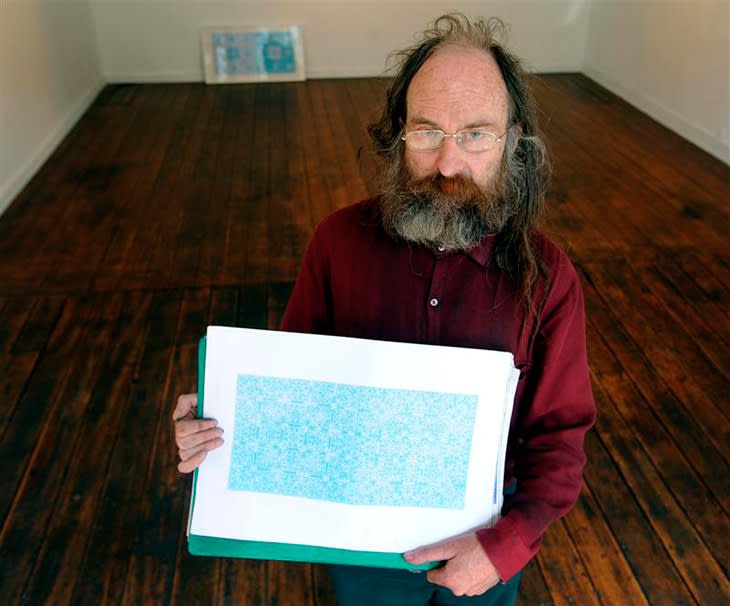

Martin Thompson, with his matted beard and long hair, was a well-recognized character in the neighborhood of upper Cuba Street in Wellington, New Zealand. The area, once known for its Victorian shops and villas, is now run-down and desolate as a result of being zoned a motorway. Nevertheless, it has served as a bohemian setting for students and artists since the drug-addled 1970s. Born here in 1955, Thompson experienced both the best and the worst of his local community. For many years, things were rough for Thompson.

Straddling the poverty line and unable to manage employment, he survived through support from a government health benefit and his own opportunistic salvaging of demolition wood. Timber became one of Thompson’s greatest passions after being trained as a wood joiner as a teenager. Coincidentally, it was also around this time that Thompson because to suffer from a mental condition that made subtle codes of social behavior both difficult and stressful. Martin’s inability to function socially is balanced by having extraordinary talents elsewhere. He is sensitive to light, color, sound and has an exceptional capacity for numbers. These gifts, along with his wood joinery skills, all come together in the artist’s drawings. Like many others, his disability overshadowed his abilities and for many years, Thompson’s condition kept him ostracized from the mainstream art world. Nevertheless, he kept creating always carrying a bundle of papers under one of his arms. The bundle contained a large pile of his drawings, some recent others in progress or old. The drawings themselves represented a dazzling array of complex graphic system that Thompson created over his life in an effort to create order and pattern. At that time, the work was sometimes shown to friends or discarded but was never exhibited or sold. Everything changed in 2002 when Thompson met with curator Brooke Anderson. Subsequently, Anderson decided to feature his work in the renowned exhibition Obsessive Drawings at the American Folk Museum in 2005. As a result, Thompson’s reputation grew and his work has been shown and collected internationally ever since. Thompson’s drawings were made from A3 or A4 graph paper and fine point ink marking pens. His process consists of meticulously applying color in sequenced rows of tiny squares. The layers combine to form designs resembling intricate quilts, radiating mandalas, or patterns of pixilated TV static. There are no tests or trial runs in Thompson’s creative process. All of the calculations in his work are intuitive, appearing on the paper with miraculous mechanical certainty. My understanding, gleaned from watching him work, is that a pre-determined sequence was set out, applied in strips, and other motifs were overlaid on top of them; this procedure afforded the opportunity to patterns in and out of the negative space.

Untitled, c. 2000, ink on graph paper, 7.28 x 10.63 in., 18.5 x 27 cm

A relationship existed between the arranged series of numbers that comprised a drawing and its particular color. In fact, the color choice is of critical significance in gauging the overall success of Thompson’s work. A new color series will not be started until an existing sequence of drawings has been completed. He may not have been able to predict the final appearance of each of his works but through his process of layering numerical intervals, he is able to both surprise himself and find delight in the complex relationships in the final outcomes.

Untitled, c. 2000, ink on graph paper, 5.9 x 13.8 in., 15 x 35 cm

An interesting aspect of Thompson’s technique is his use of a scalpel and clear tape to cut and insert segments from one drawn sequence into another in order to compound the layering into consistent piece. The back of his drawings were often a woven matrix of clear tape but the artist’s uncanny control of his cutting process became evident in the joint lines on the front surfaces of his work. In a sense, they almost defy recognition until closer inspection. The precision employed in Thompson’s work is notable considering he often works in his own lap or at a local coffee shop or bus shelter.

Untitled, c. 2000, ink on graph paper, 7.5 x 10.8 in., 19 x 27.5 cm

In 2007, the motorway was constructed through his old neighborhood in Wellington and in 2008, Martin moved to Dunedin in the South Island of New Zealand to be closer to his family. The quirky yet brilliant man continues to thrive and his ambition endures through the exactitude, effort, and appreciation of his work..

Untitled, c. 1995-98, ink on graph paper, 7.28 x14.57 in., 18.5 x 37 cm

An essential part of Thompson’s process is constructing his drawings in pairs. This particular method manifests in positive and negative spacial patterning that married technical precision with mathematical acme. One finds themselves drawn to the appearance of incidental designs, diagonal pathways, and visually meditative musical structuring. This particular act of drawing seems to have evolved as a coping mechanism for the chaotic and imperfect world Thompson was subjected to. Similarly to the American artist Agnes Martin, who also used grids to sustain focus and perfect handcraft, Thompson’s obsessive filling of miniature squares while counting and dividing serves to occupy his mind and filter proverbial noise. Much like Martin, Thompson creates to empty his mind, not think about himself, and create a sublime world apart from the one he is living in. Beyond emotional circumvention, Thompson created psychedelic trips. His formative teen years peaked in the midst of the acid-happy sub-subculture of the 1970’s influencing the retinal stimuli and visually dazzling “wow factor” in the artist’s work. As such, Thompson’s art is just as ubiquitous with the day-glowing hippie as it with the minimalist elite.

Untitled, c. 2011, ink on prepared paper, 26 x 26 in., 66 x 66 cm

Additionally, Thompson’s drawings were a practice of perfection, always aiming to transcend superiority. Even before his work was acknowledged by the public, he took pride in doing his best. Any mistakes, miss-marked lines, and failed cuts would be registered by the artist with outrage. However, the artist manages to repair and reconstruct imperfections with scalpels and tape to maintain the exceptional craftsmanship present in his work.

Untitled, c. 2000, ink on graph paper, 7.5 x 10.82 in., 19 x 27.5 cm

Stuart Shepherd is a visual artist and a curator . In 1997, he met Martin Thompson while working as a tutor at a local community art workshop. In 2004, he introduced Thompson to Brook Anderson of the American Folk Art Museum and his work was acquired for their important exhibition “Obsessive Drawing” in 2006.