Now that the legendary Mexican outsider’s “last works” have surfaced, and better-informed research about his life has been published, new ways of appreciating his achievements are emerging, too. –By Edward M. Gómez

Who was Martín Ramírez? What does his work mean?

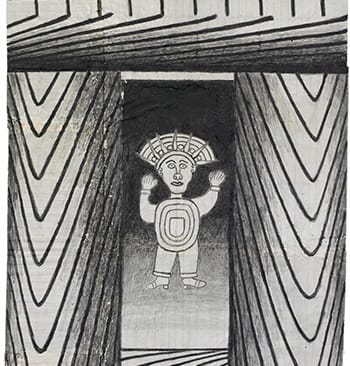

Untitled (Aztec), detail, c. 1960-63, gouache and graphite on pieced-together paper, 24.5 x 15 in., 62.2 x 38.1 cm.

Those are the questions that have long intrigued admirers of the skillfully composed, mixed-media works on paper of the Mexican-born self-taught artist, whose life story has become something of a legend in outsider art’s still-unfolding history, and who has earned a secure place in the field’s canon of most-remarkable talents. Indeed, those two questions lie at the heart of many an investigation of the life and accomplishments of any artist; as starting points for inquiries in the fields of art and cultural history, they might be posed like this: Who made this, and why?

Except, of course, when that is not the main question a researcher might ask, as when those who take a postmodernist critical approach to their subject matter, downplaying the usual concern about a single work’s or a body of art’s authorship, focus instead on the conditions or circumstances–social, cultural, political, economic, historical–in which a particular form of artistic expression develops or from which it has emerged. Postmodernist theory is concerned with what it regards as the varying, inevitably shifting contexts in which anything–a song, a dance, a speech, a picture, a historical event, etc.–might be perceived. As such contexts, or the points of view of the individuals or groups that observe or experience something, change, so do the meanings of whatever is being or has been observed.

By contrast, a so-called formalist approach to understanding and appreciating a work of art assumes that it can and will effectively convey to a viewer whatever it has to say–whatever its creator intended it to express–without the intervention of any kind of analytical or interpretative frameworks or theories, or maybe even without any explanatory, biographical information about its maker. For a strict formalist, form is content, and therein resides a work’s meaning. Likewise, any work can, does and maybe even must speak for itself.

Untitled (Arches), c. 1960-63, gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper, 28.5 x 7.3 in.

However, notes Víctor M. Espinosa, a lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Ohio State University, in Columbus: “From the sociologist’s point of view, the work of art can never speak for itself. The sociologist believes that the work of art also has meanings that are constructed socially.” Espinosa notes that it is art critics and other observers of works of art who derive meanings from or imbue them with meanings. He adds: “That’s why Ramírez’s work was thrown in the trash in the 1950s–

[precisely] because it couldn’t speak for itself. Someone had to speak up on its behalf, pointing out its significance in certain contexts, such as in an art-historical context.” At Dewitt State Hospital in northern California, the psychiatric hospital in which Ramírez spent the long, latter part of his life, the intervener who recognized the diagnosed schizophrenic’s creations as works of art was Tarmo Pasto, a professor of art and psychology from a nearby college. He visited Ramírez regularly after first meeting him at Dewitt in 1950, gave him art supplies and showed his drawings in public exhibitions.

Readers familiar with the writings about Ramírez’s life and work that have been published to date will recognize Espinosa as the co-author or author of essays that have presented his and Kristin E. Espinosa’s valuable findings from the pioneering research they have conducted in Mexico and California. Over the years, they have spoken with surviving relatives of Ramírez and with former Dewitt employees who had known of him or had interacted with him there. The Espinosas tracked down documents, such as the artist’s Dewitt medical records. They co-authored the main essay in the catalog of the Ramírez retrospective that was organized by and presented at the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM), in New York, in 2007. During its run, the artist’s so-called last works were discovered in the home of relatives of Dewitt’s last, now-deceased director, a physician who had dated and kept more than 140 drawings Ramírez had made during the final years of his life.

Untitled (Parade Horse and Rider with Bugle and Flag), c.1960-63, gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper, 16.5 x 21.5 in., 41.9 x 54.6 cm., private collection.

In 2008, AFAM showed some of those well-preserved drawings, immediately prompting a re-examination of much of what had hitherto been understood about the scope and character of Ramírez’s artistic production. That reconsideration of his oeuvre continues today, especially since the “last works” are being brought to market not all at once, but rather in batches by Ricco/Maresca, the New York gallery that commercially represents the Estate of Martín Ramírez, a legal entity controlled by a group of the artist’s descendant-heirs. As each new selection of his “last works” enters the world, the public has an opportunity to learn more about the breadth and richness of Ramírez’s artistic achievement. “It’s a big responsibility handling work of great aesthetic and historical value like this,” says dealer Frank Maresca. “Each new showing of pieces from the ‘last works’ becomes a historic event in this field, affecting the way Ramírez’s work is understood.”

Víctor M. Espinosa, who himself is Mexican, also wrote an essay for the catalog of the 2010 exhibition of Ramírez drawings that was presented at the Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. That text is filled with well-substantiated information about the artist’s upbringing in Mexico and aspects of his native region’s rural landscape that became the subject matter of his art. In that essay, Espinosa wrote: “The fact that we do not have any testimony about [Ramírez’s] intentions as an artist has generated a great deal of speculation about the possible significance of the central themes of his work. The 450 [Ramírez] drawings that it has been possible to locate to date are, therefore, our primary available source from which to explore [his] vision and chart the worldview they embody.”

Untitled (Frame), c. 1960-63, gouache and graphite on paper, 8 x 5 in., 20.3 x 12.7 cm.

We do not have and we may never have any reliable record indicating exactly why Ramírez created his extraordinary pictures or what he meant to convey by them (or to whom; did he even have an audience in mind?), but the Espinosas’ dogged research has filled in many of the blanks concerning the artist’s life story. The information they have dug up has helped debunk earlier misunderstandings about it. For example, just a few decades ago, when Ramírez’s work first began to attract the outsider art world’s attention, some observers hypothesized that the artist’s bio-cultural roots lay with those of some of modern Mexico’s indigenous peoples. In fact, though, as Víctor M. Espinosa has pointed out, Ramírez came from the Los Altos de Jalisco region of the state of Jalisco in west-central Mexico, where criollos (descendants of Spanish settlers, with enduring, strong ties to Spain’s culture and traditions), not mixed, Spanish-and-indigenous mestizos, were dominant.

In 1981, a text about Ramírez by Roger Cardinal was published in a British art-therapists’ journal. It stated that the artist had “lacked the capacity for oral speech” and proposed that, through his art, he “tries to speak to us about his experience of psychosis, of acutely reduced contact with normal experience,” adding that “[h]e communicates to us a sense of desperate fragility and uncertainty.”

Based on the incomplete information or misinformation that was available at the time, one might have assumed that Ramírez could not speak. However, later research showed that perhaps he had chosen not to speak. Overall, such observations helped establish a perception of Ramírez and his work that has long endured.

Similarly, the American art critic Roberta Smith’s appreciative essay about Ramírez’s work, published in the catalog of an exhibition of his drawings that was shown at Moore College of Art and Design, in Philadelphia, in 1985, unwittingly got it wrong when it stated that the artist had “stopped speaking in 1915.” If, indeed, for whatever reason, he had stopped talking around the age of 20, how would he have been able to communicate with his family and, for example, with the fellow jaliscienses who had left the Los Altos region with him in the late 1920s to head north in search of work in the U.S.?

Smith also wrote, again helping to establish a lasting view of Ramírez and his art: “The more you look at Ramírez’s work, the more it seems in some profound way to make perfect sense, to be completely of its time and place–even if we can’t get at all [of] the corroborating facts….Did he make it up in a kind of visionary spontaneous combustion that the naïve, insane or devout are sometimes capable of? Or was it a freak copying skill coupled with a genius for abstract doodling that enabled him to elaborate on a handful of magazine images to which he was irrepressibly drawn?”

Untitled (Triangle Landscape with Train), c. 1960-63, gouache & graphite on pieced paper, 13.5 x 23 in., 34.3 x 58.4 cm. These three drawings from the artist’s ‘last works’ (c. 1960-63) depict some of Ramírez’s basic compositional motifs.

That kind of language, at once admiring of Ramírez’s evident artistic talent, was also pejorative; why shouldn’t his art make “perfect sense” any less than, say, the work of Pierre-Auguste Renoir or Andy Warhol or Damien Hirst? And maybe there never was any “abstract doodling” at all in Ramírez’s work. Perhaps the artist consciously chose how to form each line and where to place each element of his compositions. Later in her text, Smith recognized this trait. She wrote: “[S]omewhere within himself[,] Ramírez was an awesomely complete artist who knew exactly what he was doing.” But doesn’t any “complete artist,” buoyed by a conscious sense of purpose, not to mention some measure of will, almost always “know” what he or she is doing, even when the doing is the brainstorming-searching-experimenting part of the creative process? Isn’t such awareness of one’s deep engagement in the creative process an essential part of being an artist? Why should the decision-making within the creative-artistic process of a diagnosed mentally ill person be any more questionable or, implicitly, somehow less “complete” than the same process as it is exercised by a supposedly mentally healthy Jasper Johns or Jeff Koons?

Untitled (Arch with Disc), c. 1960-63, gouache and graphite on paper, 8 x 6 in., 20 x 15.2 cm.

The formalist approach to appreciating and, at best, to understanding any artist’s work would take Ramírez’s images at face value, on their own terms and, while possibly looking for specific points of reference in his iconography (what, in the “real” world, might have inspired his depictions of certain buildings, animals or vehicles, for example), ideally would make no assumptions about the artist’s communicative intentions or the implied or symbolic meaning of the content of his works.

By contrast, Víctor M. Espinosa’s investigation of Ramírez’s life story and art has eschewed conjecture and critical analysis in favor of historical facts. He notes: “The research I do tries to present the most complete information and clear away the myths and speculation” that have persisted with regard to the artist’s biography and the circumstances in which he evolved as a person and created his art. In the introduction to an as yet unpublished “sociological biography” of Ramírez that Espinosa has been working on, part of which he showed me in draft form, he explains that he is interested in better understanding the artist’s “life experiences, the construction of his otherness and [his] reputation as an Outsider master.” His research, he writes, aims to show “how a Mexican-immigrant worker without artistic credentials came to be situated as a perfect paradigm of Outsider art by some scholars…and hailed by influential New York art critics….”

Espinosa has sought to identify documentable sources of Ramírez’s imagery and the historical, cultural and social conditions or forces that helped shape his art and out of which it emerged, both in Mexico, before the devoutly Catholic ranchero left his homeland, and after his arrival and hospitalization in the U.S. Espinosa has identified, for example, two churches from Ramírez’s native region that turn up routinely in his drawings: the Santuario del Señor de la Misericordia in Tepatitlán and the Capilla de Milpillas, where he had worshipped and where, in 1918, he married his wife. The latter church, the Espinosas noted in their 2007 AFAM catalog essay, “still preserves the oil painting and the small statue of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, or La Purísima, that almost certainly inspired Ramírez’s Madonnas.” Espinosa also points out: “To Mexicans looking at Ramírez’s work, a lot of what is recognizable in it is obvious⎯the colonial architecture or the Catholic religious iconography, for example.”

Untitled (Horse and Rider with Large Bugle), c. 1960-63, gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper, 11 x 17 in., 27.9 x 43.2 cm. Courtesy Robert A. Roth.

Clearly, Espinosa is no formalist in his approach to exploring and trying to better understand different aspects of Ramírez’s life and art. However, speaking about art in general, he concedes: “With regard to any work of art one might consider, a big question has always been: Whatever it might be about or whoever made it, does it have some special power that attracts us, some kind of intrinsic aesthetic value?” The now-retired, American art dealer Phyllis Kind, who first brought Ramírez’s work to market in the U.S., repeatedly said that she sought just that type of urgent but ineffable quality in whatever art, contemporary or outsider, she showed. As self-taught artists’ creations became increasingly popular in the cultural mainstream, she advised their admirers not to lose sight of what made them unique, again alluding to their aesthetic allure, or that “special power” to which Espinosa also refers.

Espinosa says that, unmistakably, there is something very potent about Ramírez’s creations, and that without this quality, they would not have provoked the interest they did when they were first recognized as art during the incurable schizophrenic’s lifetime (that was his ultimate diagnosis) and, later, when they were re-discovered by the international art market in the 1970s. Interest in Ramírez’s art has only increased since then; today, notes dealer Maresca, his “last works” range in price from around $60,000 to $500,000 for very large pieces.

Untitled (Alamentosa), c. 1953, pencil and watercolor on paper, 80 x 34 in., 176 x 93 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

That special quality that pulls us toward the works of Ramírez and other distinctive outsiders was, in effect, the subject of all of the works on view in “Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing,” an exhibition shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2008. Its organizer, Connie Butler, MoMA’s chief curator of drawings, told me that, in assembling this selection of works by both academically trained and self-taught artists (Louise Bourgeois, Öyvind Fahlström, Jim Nutt and James Lee Byars among the former; Minnie Evans, Bill Traylor, Dan Miller and Joseph E. Yoakum among the latter), she was interested in calling attention to “a shared visual language” among makers of drawings, no matter what differences might have existed between their backgrounds or working methods, or their relative involvement in or isolation from the cultural mainstream.

“I was interested in a certain kind of spirit or intensity or psychological charge that a lot of the work had,” Butler said. That characteristic is found in Ramírez’s work, she noted, pointing out that MoMA now owns two of his drawings. One of them, the large Untitled (Alamentosa), circa 1953, features a composition consisting of three distinct sections, whose illusions of physical depth Ramírez masterfully created with his signature, form-shaping, repeated diagonal and curved lines. Through two of these sections, trains barrel down neatly rendered tracks. MoMA also owns a small Ramírez image of a jinete, or Mexican horseman, a donation from the estate of the late Chicago artist Ray Yoshida, who had been Nutt’s teacher and a mentor to artists in the Chicago Imagists’ circle of the 1960s and 1970s. Many of those artists were deeply interested in folk art and outsider art, as was Phyllis Kind, who showed their works and outsider art at her now-defunct Chicago gallery.

Why should Ramírez or other outsiders’ works be on view at all at a museum like MoMA, one of the world’s premier repositories of modern art masterpieces and a guardian of modernism’s established, canonical history? Partly, Butler explains, it is “because curators of my generation are interested in examining and presenting the histories of ‘multiple modernisms,’ not just the history of modern art with which many people are familiar.” But outsider artists were not conscious, active participants in the formulation of modernist aesthetic principles or styles or art-making techniques; the whole point about their uniqueness is that they created their work apart from such mainstream currents.

Tarmo Pasto giving a lecture at Mills College in Oakland, California, in January 1954.

Nevertheless, Butler says, many modern artists were interested in the work of folk and other self-taught artists. Examples include early 20th-centry American modernists and, in Europe, Jean Dubuffet, who prominently championed the work of art-makers from way beyond the cultural mainstream. MoMA was founded in 1929, and from its start has taken a curatorial interest in subjects that have influenced modern art’s development. In 1932, for instance, it presented the exhibition “American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900.” A tendency in folk art and outsider art that interests her, Butler says, “is an expression you often find of extreme religious zealousness or patriotism or sensory experience or, say, an exaggerated view of the world.” It can “also be found in the work of many trained artists, I suppose,” she adds, but it was definitely in evidence in “Glossolalia.”

Untitled (Man Riding Donkey), c. 1960-63, gouache, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 22.5 x 20 in., 57.2 x 50.8 cm.

Turning back to formalism, which also looks for formal and technical affinities between different works of art: It certainly finds them between, say, some of the repeating, simple-form compositions in Ramírez’s “last works” or the basic geometry of Bill Traylor’s colored-silhouette drawings and the works of minimalist artists and those who, like some post-abstract-expressionist painters, made pictures–even shaped canvases–whose subjects were pure color or pure form. Or between the imaginary worlds depicted by some self-taught artists, inspired by dreams or visions, and the wildly subject-juxtaposing images the surrealists cooked up. Or between Thornton Dial and other self-taught artists’ inventive assemblage sculptures and the long tradition of modernist, constructed sculpture that began with cubist experiments and has continued through mixed-media installation art.

Similarly, the 2009-2010 AFAM exhibition “Approaching Abstraction,” while highlighting ways in which self-taught artists had explored color, line, composition and texture in their work, steered an examination of their art away from its representational or narrative aspects and a preoccupation with its makers’ biographies. Instead, it implicitly invited comparison between the abstract qualities of certain self-taught artists’ creations and the expressive, visual language of mainstream modernists who had worked or who work in abstract modes.

Víctor M. Espinosa and other observers have pointed out that, as an immigrant to the U.S., Ramírez was a “transnational” artist whose life experience spanned two different cultures. He was a witness to, or his life was affected by, some of the biggest events of the early 20th century, including the Mexican Revolution (1910-1929); the Guerra Cristera (1926-1929), a civil war in Mexico between anticlerical, central-government forces and Roman Catholic Church supporters; and the Great Depression, which began in 1929. Ramírez experienced dramatic social and cultural differences between the rural, agricultural environment of his Mexican upbringing and that of the technology-driven, urban centers of California, in which he spent the latter part of his life and where he saw, for example, the trains that seized his imagination and became a main subject of his art.

Untitled (Landscape), c. 1952, courtesy of AFAM

We may never know for sure all the details of Ramírez’s life or exactly what motivated him to make his drawings–and maybe that uncertainty is alright. In her 1985 text, Smith observed that “Ramírez’s talent may remain among the most intriguing riddles” of 20th-century art. However, perhaps it’s not his talent per se that should be seen as “intriguing.” It was what it was, and to even implicitly question its source, authenticity or legitimacy–is there any reason why a schizophrenic from a poor, rural, Mexican pueblito should or could not have had the talent to make fascinating, technically sophisticated art?–is patronizing and gratuitous. What are intriguing are the still-undeciphered meanings of Ramírez’s creations. So is his unknown purpose for making them, about which he left no clues.

It is those parts of the Ramírez enigma that contribute so much to his art’s allure if, of course, one is not a strict, formalist and does want or need to consider biographical or other contextual information about the artist and the circumstances in which he produced his work in order to “make sense” of it.

“Art’s best moments are when it forgets what it is called,” Dubuffet once observed–and perhaps also when, for those ofus who urgently want to know more about its makers and their intentions, we stop and simply let it exert its power to seduce and transport us–before getting back to the serious business of trying to solve its most challenging riddles.

Edward M. Gómez (www.edwardmgomez.com) has written about Adolf Wölfli, Hans Krüsi, Japanese and Jamaican outsiders, and other artists for Raw Vision. He is the author or co-author of numerous exhibition catalogs, including Yes: Yoko Ono (Harry N. Abrams, 2000), The Art of Adolf Wölfli: St. Adolf—Giant—Creation (American Folk Art Museum and Princeton University Press, 2003) and Hans Krüsi (Iconofolio/Outsiders, 2006).

Except for Untitled (Alamentosa) and Untitled (Landscape), all works reproduced here have been provided by Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York. All works © the Estate of Martín Ramírez.

This text © 2013 Edward M. Gómez; all rights reserved.

FLUENCE is published by Ricco/Maresca, New York. The design and appearance of the content of this electronic publication © 2013 Ricco/Maresca. Unless otherwise indicated herein, the various texts, images and other written, visual or audio-visual components of this publication are the copyright-protected property of their respective creators.

This is a longer version of this essay, which was published in the print edition of Raw Vision, the U.K.-based, international magazine about the lives and work of outsider and self-taught artists. See issue number 77, winter 2012/2013, and www.rawvision.com.