Using unusual methods, photographer Amanda Means captures the essence—and simple majesty—of her [non-human] portrait subjects in riveting detail

Like a philosopher who makes a habit of contemplating the metaphysical, the very nature of reality and being, Amanda Means has long made the essence of the subjects of her indelible images—see them once; remember them forever—the subject of her photographs and other works.

“I grew up on a farm in upstate New York, near the border with Canada,” the artist says, adding: “My family owned and operated apple, peach and cherry orchards on the south shore of Lare Ontario. We lived in a stone farmhouse that had been built in the 1800s, so I grew up feeling very close to nature and I was interested in plants and the shapes, colors and textures of living things.”

Means, in her studio in Beacon, New York, examining her photos of New York City from the late 1970s, in which she explored her interest in shapes created by shadows in an urban environment.

After earning an undergraduate degree from Cornell University, Means earned a master’s degree through a program offered by the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester. Founded by the photographer and curator Nathan Lyons in 1969, that pioneering media-studies center offers courses in art theory and criticism, conventional and digital photography, bookbinding and other visual-arts techniques. Today, it administers its MFA program in conjunction with the State University of New York at Brockport, near Rochester. (When Means studied at VSW decades ago, SUNY Buffalo served as the still-young art school’s academic partner.)

Abstract-shape, black-paper collages from the artist’s notebooks of the 1970s.

In the late 1970s, Means moved to New York. It was, she recalls, a period of big changes in her life, not only on account of the culture-shock jolt of her move from the rural setting of her childhood to the densely populated, concrete jungle of Manhattan, but also because her family had lost ownership of its farm, and her father had died. Those events profoundly moved the young artist, provoking a mix of emotions that inevitably blended with the sensations and stimulation that came with her move to energetic New York.

Color photographs made with a large-format Polaroid camera. Left to right: Light Bulb 008BYo, 2007; Light Bulb 004POi, 2007; Light Bulb 007GOa, 2007. Each photo: 24 ins. x 20 ins.

In the city, Means brought her keen eye for the shapes and details of the natural world to her exploration of the human-constructed, urban environment. Already deeply interested in abstract art’s examination—and celebration—of pure form and in its frequent palette of stripped-down, basic black and white, Means filled notebooks with studies of abstract shapes cut out of black paper.

Echoing those form-finding experiments, her black-and-white photographs of everyday urban scenes of the late 1970s captured the play of sharp-edged shadows on streets, sidewalks and the sides of buildings, as well as the jazzy sense of choreographed chaos that characterized the movement of people and traffic in New York. “For me, the atmosphere in the city was something new and different,” Means remembers. “When I look back at my photos from that time, I see that they also captured the moods of the city that I was noticing; sometimes they were full of energy and sometimes they were unexpectedly calm and quiet.”

Two of the artist’s photographic “drawings” made by shining the beams of penlights (tiny flashlights) at photo- sensitive paper. Left: Abstraction 15, 2005. Right: Abstraction 6, 2005. Each photo: 24 ins. x 20 ins.

If that stillness caught the young artist’s attention, it might also be said that Means has long brought a sense of meditative focus to the way she has observed and represented her subject matter in monochromatic ink drawings on paper and in a diverse range of photographic images. The meticulousness with which she executes her photographs, the works for which she has become best-known, reflects this sensibility. It’s a way of looking at and capturing images of the world that is at once scientific and artistic.

In the 1980s, Means became expertly skilled at printing photographs—so much so that, after Robert Mapplethorpe saw some of her large-scale landscape photos at New York’s Zabriskie Gallery, he contacted her and hired her to make large-format prints of some of his own increasingly popular—and increasingly notorious—black-and-white photographs, many of which he produced in series.

Left: Water Glass 10, 2004. Right: Water Glass 2, 2004 Each photo: 50 ins. 40 ins. In focusing on various everyday objects as the subjects of her photographs, in effect Means has created portraits of these otherwise mundane items.

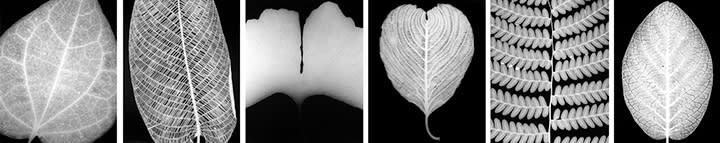

Since that time, Means has created several different photo portfolios of her own. Among their subjects, whose forms are sometimes simple and sometimes remarkably complex: leaves, flowers, light bulbs and water glasses. Means has shot some of her subjects straight on, like iconic monuments, allowing them to fill each photo’s frame.

To shoot a wide variety of leaves and plants that she gathers herself, she uses no photographic negatives at all. Instead, she explains, “To make the flower images, for example, I put a flower into an antique, wooden, 8-by-10-inch camera that I adapted to make into a horizontal enlarger. The light source behind the flower is a 10-by-10-inch bright light source. This light passes through the flower and through the lens onto photo-sensitive paper that is tacked onto the opposite wall.” Means’s technique produces negative images whose fine, white details—the delicate veins of a leaf, the voluptuous volumes of fluffy flowers—stand out dramatically against velvety-black backgrounds.

The artist looks through a portfolio of her photographs of flowers, which were made in the darkroom without the use of conventional film negatives.

Means observes: “It’s amazing how much each photograph reveals. It’s not just the shape of a flower or a leaf but also the complex structure of a plant’s architecture and maybe even something about its soul.” In effect, Means’s tightly cropped, straight-on photographic images are sensitive portraits of her non-human, often ordinary subjects. More recently, using penlights whose beams she shines on photo-sensitive paper in the darkroom to create lively, dynamic abstractions, Means has been “drawing” with light itself. “I’m still experimenting with this technique and I’m excited about where it may lead,” she says. Bold and distinctive, these new works are the latest addition to this inventive artist’s still-evolving collection of emblematic images.