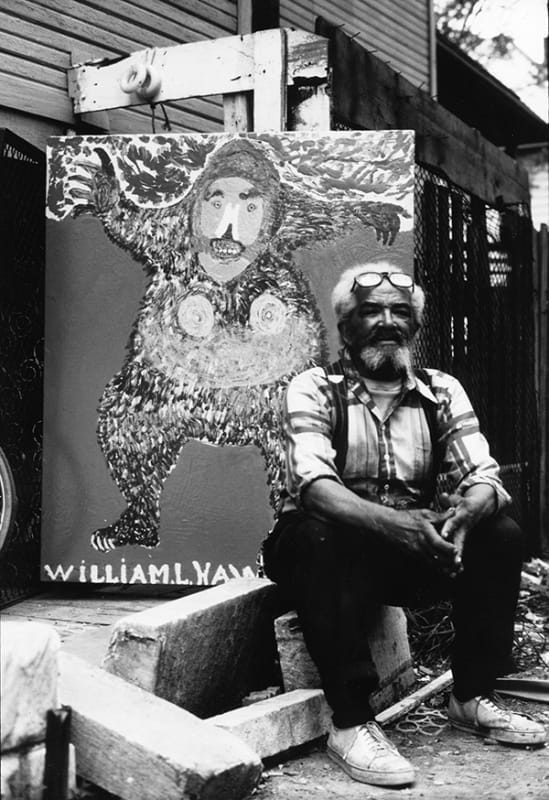

To accompany William Hawkins on his walks through the streets of Columbus, Ohio, was like following an experienced prospector in search of gold. Hawkins’s selective eye seized images from newspapers, magazines, and advertisements, which he habitually salvaged from dumpsters and kept in a suitcase for reference and use in his works. Hawkins combined these images with his own recollections and impressions to create a vivid picture gallery of animals, American icons (such as the Statue of Liberty and the Chrysler building), and historic events. Although the artist could barely read and write, he transformed words themselves—usually his signature and birth place and date—into powerful graphic elements within his works.

Born in rural Kentucky, Hawkins moved north to Columbus Ohio in 1916, where he lived for the rest of his life. His early years in Kentucky provided him with a knowledge and love of animals—an awareness that informs even his most fantastic dinosaur paintings. In Columbus, Hawkins held an assortment of unskilled jobs, drove a truck, and even ran a small brothel. He was married twice and claimed to have fathered some 20 children. Although he was drawing and selling his work as early as the 1930s, he did not begin painting in the style for which he is best known until the mid to late 1970s. He worked almost without letup thereafter, in spite of illness and advancing age.

At first, Hawkins used inexpensive and readily available materials: semi-gloss and enamel paints in primary colors (tossed out by a local hardware store) and a single blunt brush. Later, when he could afford it, he painted on Masonite, which he preferred because it did not “suck up the paint” like cardboard or plywood. Sometimes he dripped paint or let it flow across the surface as he tilted it so he could, as he put it, “watch the painting make itself.” He often painted elaborate borders around his pictures and attached such materials as wood, gravel, newspaper photos, or found objects.

Hawkins suffered a stroke in 1989 from which he only partly recovered. He died months later, in 1990. The artist once summed up his creative aspirations by remarking: “you have to do something wonderful, so people know who you are.”