Outside In

Ultimately, all artists are the same. They are there before the crowds come and remain after they leave. They work, leaving behind them a trail of self-indulgent productions without much care for what will be done with them or thought of them.

They say they are doing it for beauty, money or fame, or for God, Allah, or a voice in their heads. Or because they are angry and this is a way to keep from hurting people. Or because they are sad or bored or happy or sex-starved or they just want to show off.

But really, they do it because they can, because the act of coaxing into form the disparate, inert materials around them is so galvanizing that it tends to cancel out everything else. There are other, better ways to make money. Art’s core is an idiot’s delight, a feedback loop, but one that winds through memory and judgment, infancy and the immediate moment. In the most extreme cases, it is the only thing holding the artist’s world together.

One thing artists do not do is make things to plug holes in art history books.

As William Hawkins never did.

Why insist on the obvious? Only for this reason. As the work of William Hawkins (1895-1990) gradually becomes assimilated into a mainstream of experience, recognition, and taste, it also becomes part of the narratives art historians and critics tell each other. And these narratives can be profoundly misleading, creating spurious analogies and obscuring deeper affinities. They threaten to connoisseur us out of our senses, as William Blake once warned. Just as leaving Hawkins out of the history books can be a distortion, including him can, too.

The first painting of William Hawkins I saw was Dragon Snake (1987), a three-dimensional painting on wood based around a piece of flexible tubing. It is a massive, shocking, fearful thing, whose gestural painting seems to unleash the energy of the construction. Gary Schwindler, the expert on Hawkins’ life, had the same kind of initial experience. “I wanted to run away,” he wrote. [1] Out of self-defense, I immediately began to put the work in the “context” of painting and so-called assemblage art—Kurt Schwitters, Robert Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain, and Jim Dine, to identify a lineage.

Trying to drag Hawkins in from the Outside and make him part of a story about modern art isn’t so farfetched. After all, the dominant mode of art of this century had been heterodox—to introduce disparate materials into the scope of a single work. Hawkins, in this sense, is de facto a modern artist, even more so because most of his paintings are based on prior images, usually photographs, not on nature directly observed. Except, as critic Jenifer Borum points out, “He didn’t share their avant-garde vision.” [2] To say the least. But placing Hawkins among artists he knew nothing about doesn’t just put his work in a new light, it changes all the work about it. Although Rauschenberg and Schwitters (not to mention Duchamp) were deeply implicated in art historical awareness, the roots of their art are idiosyncratic. And although the currents of the time gave these artists a kind of permission to practice as they did—and gave Hawkins permission, too, in a strange way—the things they did are sudden, surprising, and never exhausted by the words they provoke.

If we can rescue Hawkins from the labels I first wanted to assign him, I believe we can also rescue a great deal of modern and contemporary art from the narratives that suppress the actual acts of making art and its psychic sources. We can tell new stories about art, that take into account individual practice, sensibility, situation, and personal meaning, not just the impersonal transformations of cultural codes.

Untitled (“Dragon Snake”), 1987. Enamel and mixed media construction on masonite. 56.5″ x 48″ x 5″

William Hawkins. Photo by Frank Maresca.

WILLIAM HAWKINS, PHOTOGRAPHER

Sometime after he got over his initial shock at seeing Hawkins’ paintings in a small gallery in Columbus, Ohio, in 1984, Gary Schwindler realized that this was as close to an authentic genius as most of us ever get and decided to become William Hawkins’ amanuensis, recording an enormous amount of what he said. Later, Roger Ricco and Frank Maresca put hours of Hawkins talking and working on video tape. In his long life, William Hawkins assumed many social “identities”—a feature of his being black, an emigrant from the rural south to the industrialized north, and economically nomadic. Crucial to his identity as an artist, however, is the time he spent, probably in the 1940s, as a “photographer” with a cheap box camera.[3]

It is not too much to say that photography made William Hawkins a painter—and an artist. On one level, photography was a relatively easy and cheap way to create representations that people would pay for. It was a lesson he apparently never forgot. He always tried to earn money by his art and was proud when he did—regardless of the dollar value. He seems to have sold drawings early on, too, but photographs gave Hawkins a full sense of the possibilities of representation—and what he needed to do.

We live in an image-choked world, but for Hawkins, the pictured in magazines and newspapers, which he hoarded in a suitcase and carefully sorted through, never overwhelmed him. They opened up the world and acted as a catalyst. These representations come to him stylistically neutral and art-historically blank, a vast, free-floating visual repertoire from which to choose. He felt that these photographs could be made more interesting, pretty, exotic by painting, and only by painting. He also knew they could save him a lot of trouble, substituting for labor-intensive elements he had trouble rendering—faces, for example. He often remarked that the pictures he collected “gave him a gift.” [4] That gift was aesthetic but it could also be spiritual and intellectual.

It is compelling to compare him with Gerhard Richter. For this German artist of the post-Second World War era, the growth of artistic practice coincided with an awareness of the ever-widening reach of photographic imagery, of its dominant propensity to push the experience of nature and even the emotions to the margins. Working only from photographs released the artist from the trauma of personal “self-expression,” but allowed him to indulge the primary narcissistic drive to paint. Photographs provided Richter a necessary restriction. For Hawkins, they granted a license.

Particular paintings show Hawkins making choices inspired by the visual content and the meaning of the photographs as he interpreted them. In some works, the photograph functions as both a visual element in the composition and a record of its origin and inspiration. To my mind, the most moving and mysterious example is the Dustbowl Collage (1989),[5] the last painting he completed before his death. Hawkins never titled his paintings; most of the titles were bestowed by his first exhibitor, the Columbus artist Lee Garret. The somber image of a dark figure in a stovepipe hat striding through what appears to be a winter landscape is peppered with small pieces of photographs—a child playing with dogs in a field, a grown-up waling with children. At the center of the painting, in a swirling vortex of paint, is a tiny fragment of a photograph of a toddler. The dark figure, which may be death or the artist, strides toward another collage element, an engraving of a bottle among sailing ships. Finally, in the top left corner, Hawkins fixed part of a liquor ad showing a woman painting at the beach, her outfit being tugged at by her boyfriend.

Untitled (“Dustbowl Collage”), 1989. Enamel and collage on masonite. 39.35″ x 48″

Here is an example of the category of “late works”—reflective images that comment on an artist’s vocation, as well as on the cycle of an individual life. Western art is rich in such images, from the Sistine Chapel to Picasso’s prints. Hawkins uses photographs to add a personal psychological dimension, the arc of his own human progress, to what is basically an archetypal image of darkness and light.

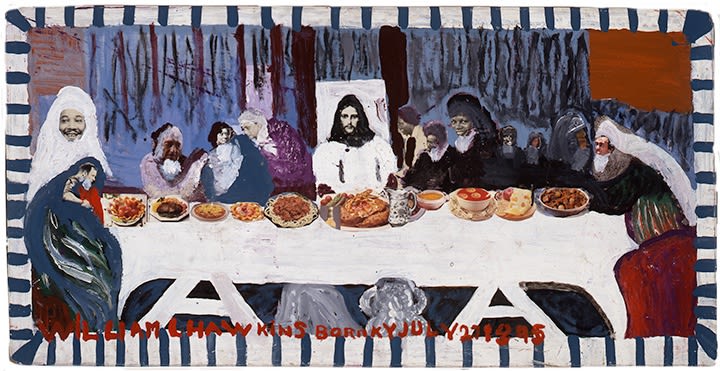

Hawkins did not always use photographs in such a complex way, but his instincts about when to paint and when to paste where uncanny. He gives his Tasmanian Tiger #3 (1989) and Orange Moose (1989) collaged eyes and transforms these two-dimensional renderings unto living creatures of the imagination. Likewise, in the Kruschev Collage (1989), by inserting a tiny photo of Soviet premier Nikita Kruschev waving into the middle of his Constructivist-inspired, red, white, and black Red Square, Hawkins evokes the absurd monumentality of Soviet military and architectural displays. Although not religious, Hawkins used Last Supper #6 (1986) to make a point about who attended that supper, or should have. He fixed photographic faces to his gathering, rendering most of them, except for Jesus, as African Americans. Likewise, to emphasize the importance if the meal, he put collage plates of food before each apostle—why not spaghetti and steak if God is picking up the check?

In all these extraordinary works, painting sustains the collage imagery that inspires and completes it. Hawkins’ borrowing displays none of the cultural knowingness of a postmodern aesthetic, but it has a specificity that contemporary art often lacks. It is exactly the opposite of Rauschenberg, who set painting and photography against each other and turned the art object into an event. In Hawkins, painting and photography confirm each other. That is because every found image posed a challenge: could he do it better? “That’s my invention,” Hawkins would say when he deliberately altered some aspect of a borrowed image.[6] And when he put his hand on it, it was his.

Untitled (“Tasmanian Tiger #3″), ca. 1989. Enamel and mixed media construction on masonite. 48″ x 48”

WILLIAM HAWKINS, PINXIT*

Hawkins is a painter’s painter. He picked his subjects because they filled his imagination—big ticket items like the Last Supper, men landing on the moon, public buildings such as Buckeye Stadium at Ohio State University in his own Columbus, and, spectacularly, animals. The shape and energy or Red Dog Running #1 (1984), the eruptive suddenness of King Kong (1985), the graphic perfection of The Bule Boar (1989), emanate from his use of contending colors, absolute in their thick solidity.

Hawkins usually worked in a basic ensemble of colors for each picture, rarely mixing, very much as Van Gogh did in his late paintings, and like Van Gogh his color combinations are seldom wrong, even—or especially—at their most extreme. Josef Albers notwithstanding, this is a God-given ability that cannot be taught. For more than their size, the fusing of image and palette accounts for the gravity of the paintings. It fixed them indelibly in the mind.

In the video shot by Roger Ricco and Frank Maresca, we can see how the artist ushered these painting into the world, through a process of careful scrutiny and total improvisation. Hawkins would set up a board on top of a makeshift table or his television set and pour paint right from the can, working in with a brush worn down to a nib. “I don’t need but one brush,” he would say.[7] He would lay down a background color and before it dried begin the central form. On the tape, his conversation is almost entirely about color, which he approached with his undivided attention. At some point he would stop, look at what he had, and contemplate his power to transform it—into almost anything. “I could put horns on it,” he might say. All the while he would search for the image to guide and inspire him, culled from his suitcase of clippings. Like de Kooning, he could return to the same image again and again, knowing it could always be different, if it was deep enough to continue to provoke him.

Untitled (“Red Dog Running #1″), 1984. Enamel on found board. 40″ x 49”

Untitled (“King Kong”), 1985. Enamel on masonite. 56″ x 46″

In truth, Hawkins was interested only in the Big Picture, the Masterpiece, so out of fashion in critical circles today. Every picture he made he signed enormously, with his name and birth date. Unable to read and write, he fashioned his signature as a message to those who could. In appropriate colors, and wherever it seemed to fit best, the message was: “this picture was impossible before I was born.”

The swagger, the complete confidence in the transformative power of the artist’s individual talent, the lack of real interest in anything outside that immediate purview, all mark Hawkins as a member of that retro crew for whom painting is the primary existential act—I paint therefore I am. Or, rather, the act of calling forth being. We can admit Hawkins into a modernist club, but this kind of hubris his longer bloodlines. In the late middle ages, the subjects of paintings were sometimes made to explain—“Hans Holbein painted me,” or “Lucas Cranach made me.” Taken the wrong way, this comes close to heresy, the pride of the demiurge.

*pinxit, Latin “he/she painted [it]” was historically inscribed after the artist’s signature in a painting to verify it.

Untitled (“The Bule Boar”), 1989. Enamel, collage, and mixed media on masonite. 55″ x 48″

THE DECORATED MAN

Right up until the stroke that led to his death, William Hawkins worked. During the day around his neighborhood, he would collect material that might earn him money—cardboard, wood, metal. Old habits die hard. At night, he painted. Any artist might recognize the bifurcated life: doing what you have to do in order to do what you want to do. Except for the outfit in which Hawkins did his manual, daytime work. Imagine Salvador Dali as a junk picker, Oscar Wilde as a chimney sweep in mauve. Hawkins wore a tuxedo shirt decorated with tacks, a jacket that glinted with pieces of metal.

He lived beyond conventional dualisms in a unified, decorated world, whose ultimate goal was not power over circumstance but beauty. In the end, beauty was the ultimate form of power. “There’s a million artists out there,” he once said, “and I try to be the greatest of them all.” He knew exactly what that meant.

I see Hawkins as an avatar of the aesthetic life, about which the philosopher Nietzsche could only preach. Hawkins the decorated man leads us beyond categories, out of the prison of objectifying, historicizing thought. He is followed by the snorting Blue Boar, the Orange Moose, the Red Dog running, the Tasmanian Tiger, and all the artists who know deep down that genius is real and that to see it in action is to be more fully alive.

*This article was originally published in Raw Vision 45.

[1] Gary Schwindler. “You Want to See Something Pretty?” in Roger Ricco and Frank Maresca, William Hawkins Paintings, New York, 1997, p,v.,

[2] Jenifer Borum, in op. cit., pg. 123.

[3] The information comes from Schwindler, op. cit., p. ix.

[4] Ibid., p. ix.

[5] The year 1989, was an annus mirabilis, yielding many of his most memorable paintings.

[6] Roger Ricco, Frank Maresca, William Hawkins, video tape, 1987.

[7] Ibid.