Letter to Kaiser Wilhelm II (1917):

Why then in evoking your memory do I vibrate like a bell announcing the nuptials of angels? Slowly dying of an ineffable love inspired in me by your splendid gaze met by chance at the Potsdam encounter in 1913. You were sparkling from head to toe, deified by the sublime beaming of your dear face.

Oh! My God, I am overjoyed.

The impulse of this enchantment brings me devoutly to my knees behind the door through which you have disappeared.

O pain. O despair! I shall not succeed in grasping the delicate flowers with penetrating scents that you involuntarily deposited in each recess of my heart immured in suffering. Would that I could temper my soul again in fire, in the star-studded heavenly eyes of an inaccessible man whom I love so madly. Only a miracle of divine love could raze the walls that eternally separate me from his love.

Aloïse Corbaz

As translated in: John G. H. Oakes, ed., In the Realms of the Unreal: ‘Insane Writings’, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York, 1991, p. 109.

Rawerotics:

adj. of or pertaining to passionate love; arousing or designed to arouse feelings of sexual desire; amorous; amatory.

n. a singular theory or science of love constructed without recourse to cultural convention.

by Colin Rhodes

GASTON DUF, Rinauserose Viltrities, 1950, colored crayon on paper, 50 x 68 cn, 19.7 x 26.8 ins., photo: Arnaud Conne, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

HEIN DINGEMANS, Ngyumpirri Rumba Rumba de Aranda Aboriginal Hoofdman, 2001, watercolor on paper, 56 x 76 cm, 22 x 29.9 ins., Galerie Atelier Herenplaats, Rotterdam

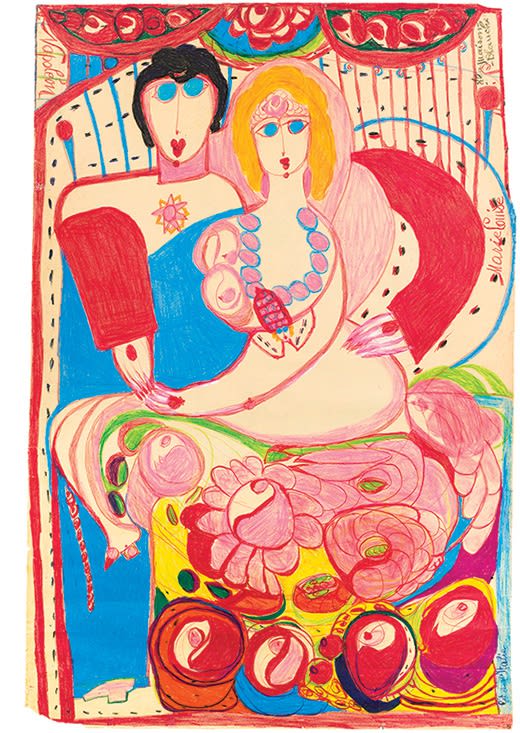

It is easy to imagine that when the physical object of sexual desire is unattainable it is likely to be sublimated in other acts and to subside into fantasy. Eroticism is conventionally thought of as a prelude to the sexual act. But it is just as likely to be part of a reorientation and transformation of sexual desire that ends in activities other than copulation, whether physical or psychological in nature. The monstrous potency of Hein Dingemans’ (b. 1962) onanists, for example, has no object other than the sexually overwhelmed singular body. But in this context it is also easy to see how the drawings of Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964), so gentle and courtly in aesthetic feel, must also be read as highly charged rawerotic machines, fit almost to burst at any moment; for here was a woman madly in love with an unattainable figure, such that she could never suppress her ardor, even from the asylum.

Furthermore, as the French cultural theorist and renegade Surrealist Georges Bataille wrote, ‘Eroticism, unlike simple sexual activity, is a psychological quest independent of the natural goal: reproduction’. (1) Essentially aesthetic in character, eroticism sets up a theatre of representation of the desired object that in turn affects the desiring subject physically and psychologically. In the case of artists, this can often result quite literally in the representation of sexual partners, removed now into the unattainable realm of the aesthetic in the very act of objectifying desire, as in the works here by Drossos B. Skyllas, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein and others. Sometimes the circle of objectification, sexual fulfilment and self-representation is offered in the most direct terms, as in the rawerotics of Ody Saban.

ODY SABAN, Un rituel de mains amoureuses, 2000, acrylic on canvas, 92 x 65 cm, 36.2 x 25.6 ins., Courtesy of the artist

For Bataille the erotic episode also amounts to an attempt, albeit temporary, to transcend the subjectivity of the individual and approach what he calls ‘continuity’ with the (discontinuous) other. ‘The transition from normal state to that of erotic desire,’ he said, ‘presupposes a partial dissolution of the person as he exists in the realm of discontinuity.’ (2) Rawerotics are without cultural constraint, driven by desire, characterized by a wide-ranging psychological inventiveness. Rawerotics inhabit territories sometimes emphatically separate to the everyday, and any dissolution of the everyday world is not a temporary event, as in the case of ordinary erotic experience. Reports posted back from encounters (both physical and psychological) in these other lands bring tantalizing insight into rich, sometimes exciting, often terrifying insight.

Paradoxically, some of the most alarming and base representations of these other worlds have been produced not by outsider writers and artists, but by more culturally-located figures such as the Marquis de Sade, in novels like Justine and The 120 Days of Sodom, and Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), much of whose work in the 1940s and 1950s was frankly sexual and, in a way, highly erotic. His Corps des dames (ladies’ bodies) series, especially, present the female body as an assertively physical combination of fluids, flesh and sexual parts. They present a kind of primeval mass of sexuality, given over to eroticism beyond the niceties of scopophilia. Unlike those multitudes of paintings of desired and idealized females coming out of classical European canons of physical beauty, these works rest instead in an entirely liberated glorying in the excess of undifferentiated physical stuff; the base matter of paint, sand, stones, and other non-painterly materials that make up the ‘body’ of each work. Dubuffet nevertheless performs a more-or-less controlled foray into the dissolute state, as is the case of the female patient in Paris’ Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital described by Unica Zürn (1916–1970) (3), or Daniel Paul Schreber’s (1842–1911) description of his own sexual degradation at the hands of God and various spirit manifestations during his ‘nervous illness’? (4) (see p. 6).

Erotic experience is undoubted in both cases, but it is also unbounded and seemingly beyond the control of the individual subject. The projection of desire into the other is turned back on the individual who in turn becomes subject. This is key in many cases with the outsiders. Stripped of the niceties of culture and in contact with the clay and primeval processes of the becoming of things, the sexualized individual may arrive at the ultimate point of dissolution. ‘Sexual union is fundamentally a compromise, a half-way house between life and death,’ said Bataille, ‘Communion between participants is a limiting factor and it must be ruptured before the true violent nature of eroticism can be seen.’ Yet for Schreber, and Zürn’s female patient, the ‘other’ is an internal or spectral figure beyond control and without moral or ethical boundaries. Similarly, this is evident in drawings by artists such as Phillip Heckenberg (b. 1952), Anthony Mannix (b. 1953), Henry Speller (1900–1996) and Gaston Duf (1920–1966).

ELIS SINISTO, performing at his property near Helsinki, 1989, photo: Jan Kaila

In cases where the physical presence of the sexualized other is missing, a focus is often provided by the production of creative works, especially writing and object- and picture-making (though one might also argue for the existence of a kind of singular, solitary, physical performance art, alluded to in Zürn’s text and Dingeman’s art, for example). In outsider art in particular, much is ephemeral, lacking a documentable history. We can only piece together the general picture of an eroticism of the excluded and isolated of society from fragmentary evidence; the texts of people writing out of their illness, such as Schreber and Zürn, the written and visual outpourings of intensely private individuals such as Malcolm McKesson (see pp. 18–19), or tales of the performances of shamanic figures such as Elis Sinistö.

Erotica are often produced out of a situation of unconsummated desire. Though, perhaps more often, they are part product of a continuum of sexual desire, anticipation, activity and reflection. Erotica (derived from the Greek eros–desire) are artistic representations that are meant to be sexually stimulating or arousing. In common with its tawdry, commercial and often illicit alter ego, pornography, in erotica the sexualized human body is the focus of representation. But unlike pornographic imagery, erotica are primarily aesthetic and engage with the human subject in a connected and less objectified way. In the creation of such work, artists establish a contact with their representation in a way that involves, inevitably, a kind of central imagining that gives life and character to the erotic player(s) as against the separateness from and even disinterestedness in character and characterization that typifies the pornographic image. Pornography is produced in a disinterested way, to be consumed by strangers, and without recourse to the sexual purposes to which images are put. Erotica, on the contrary, is engaged and connected. Audiences that are not the artist (who, of course, is also audience) join a continuum of reception and interaction with representations in which the artist is more centrally located. Moreover, it is much more likely that erotica can be regarded aesthetically without the central sexual demand in pornography that results either in a response of sexual arousal or revulsion.

Remarkably little of the significant volume of self-taught and outsider art that exists today could be placed in the category of erotica. Representations of the sexualized human body make up only a relatively small proportion of its images. In spite of the frank eroticism in Dubuffet’s work, it is interesting how little of his Art Brut collection is itself frankly erotic, though the poignant, gentle eroticism of Aloïse is worthy of mention. Erotica do appear, though, in all the tributaries of self-taught and outsider art, from mental health through mediumism, the contemporary folk environment and intellectual disability. And in general, sexual passion and desire are hardly absent. But that passion must have an object, and in this field the object is so often sublimated in other things. Fetishism is common: symbolic objects come to stand for and replace anatomical parts, which in turn signify the sexualized body. For example, Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930) commonly includes vögeln (a variation on ‘little birds’ and slang for sexual intercourse) in his drawings, which simultaneously displace and draw attention to the, for him, desired and to be feared vagina.

PAUL LANCASTER, Summer Dream, 2000, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 101.6 cm, 30 x 40 ins., collection Grey & Linda Carter

Perhaps in the absence of any practical knowledge of the desired female body, which complicates the fetishistic idea, Roy Wenzel (b. 1959) fixes on hair and particularly shoes. Passion can be modified by fear and displaced in other objects or carried over into obsession or compulsive behaviour. Sexuality can be openly fixed upon, as in certain works by Thornton Dial, Josef Schneller and Anthony Mannix, but often it is invested in other obsessions: the sexual impulse transformed into calculations and charts, paranoid fixations, or even just the plain, if obsessive, act of art-making.

Some of the founding myths of outsider art rest on the supposed liberation from social convention that madness brings, as was the case with André Breton’s obsession with Nadja (b. 1967), the young woman whose psychic deterioration provides the narrative thread for his novel named for her. As proof, critics will often point to psychiatric reports of patients who had previously been quiet, upstanding citizens using profanities and liberal references to sexuality and sexual acts without inhibition (along with, it must be said, reporting visions, threatening violence and so on). This has been taken, at times, as a sign of a person’s unconscious mind bubbling to the surface, or of consciousness in the raw. To this we might also add issues of the sheer sense of the aloneness of many artists, either through their literal separation from other people or by a psychological distancing. Boredom and frustration, whether born of incarceration, loss of a loved one or an inability to ‘connect’ socially, can be strong drivers of the impulse to art-making. Furthermore, it is certain in the case of McKesson, and possible in those of many others, that the very process of production of creative work was in itself erotic.

THORNTON DIAL, Untitled #6, 1999, graphite and pastel on paper, Ricco Maresca Gallery, New York

An abiding question about much of the self-taught and outsider art that is in the public domain today is that of permission: can public audiences always assume a right to consume these works? The question arises primarily because in very many cases works had no public audience during the lifetime of the artist, or, in the case of much work produced before the 1960s in psychiatric hospitals, consent was not sought before work was taken from patients, and therefore we seldom know the artists’ wishes. Yet some of the most interesting and visually powerful outsider art is also intensely personal and explicitly not intended for a general audience, although imagined particular audiences are not uncommon, from spirit presences to God. This is further complicated in the case of erotica, where art production as private or hermetic act is joined by visual and psychological content whose exposure has in general been regarded conventionally as restricted. The converse also applies, however. There is much sexually explicit material–work by Thornton Dial, Purvis Young (1943–2010), Paulus de Groot (b. 1977), and Ody Saban, for example–that is supposed to be seen by many, and it is interesting to speculate how much more frankly erotic work than non-erotica was suppressed and destroyed in the past, and, indeed, how much is so today in the workshops and art therapy units from which such a large proportion of contemporary outsider work emerges.

One thing is for sure: rawerotics permeate self-taught and outsider art. In their contributions to this volume Michael Bonesteel, Jenifer P. Borum, Roger Cardinal, Laurent Danchin, Françoise Monnin and Thomas Röske explore different aspects of the global production of outsider erotica, from the highly structured and controlled environment of the closed psychiatric hospitals of the last century to freewheeling idiosyncratic artists working in the seldom-visited hinterlands of the mainstream artworld. What is revealed here is not only the appearance of erotica in all of the tributaries and associated tendencies of outsider art, but also eroticism’s play across gender and sexuality. The erotica in this book is not merely a parade of male heterosexual desire made manifest in visual art, but also a presentation of erotica by women and homosexual men. Paulus de Groot’s gay erotica straightforwardly explores an assured, self-confident sexuality, whereas the erotic representations of Schreber and McKesson are altogether more equivocal and shot through with guilt and self-disapprobation. This very variety, though, is part of the interest of the whole; at times amorous, ardent, passionate and sensual, it may also be lewd, salacious, and prurient. For many audiences, of course, it is all, always indecorous and unseemly.

ROY WENZEL, Venus of the Stiletto Pumps, 1990s, pencil & oil pastel, 65 x 50 cm, 25.6 x 19.7 in., courtesy of artist

Excerpt from the book, Raw Erotica: Sex, Lust and Desire in Outsider Art, published by Raw Vision. The design and appearance of the content of this electronic publication (c) 2013 Ricco/Maresca. Unless otherwise indicated herein, the various texts, images and other written, visual or audio-visual components of this publication are the copyright-protected property of their respective creators.

Colin Rhodes is Director of STOARC (the Self-Taught and Outsider Art Research Collection), which is based at the University of Sydney. STOARC consists of a growing study collection of Australian and international Self-Taught and Outsider Art, the International Journal of Self-taught and Outsider Art, and Callan Park Gallery, which has a rich public program of exhibitions of established and emerging figures within the field.