An exhibition of the self-taught master’s images of buildings and monuments calls attention to his vision of the urban landscape

To make a living, the self-taught artist William Hawkins (1895-1990) tried his hand at just about everything during his long life—raising farm animals, serving in the U.S. Army in World War I, working as a plumber, driving a truck and even running a bordello. Similarly, when it came to making art, very little escaped the eager grasp and transformative power of his imagination.

At Hawkins’ home in Columbus, Ohio, in the early 1980s, the young artist Lee Garrett, a recent graduate of Ohio State University, discovered the older man’s artwork. He also learned that he had been a pack rat for a very long time. In Hawkins’ apartment, located one floor above a barber shop, Garrett found that, over the years, the eighty-something art-maker had amassed an astonishing array of cast-offs, including old pipes, appliances, motors, wheels, pieces of sheet metal, cans of house paint and weathered boards.

Parliamentary Buildings with Three Girls, c. 1986, oil enamel and collage on Masonite, 39 1/2 ins. x 48 ins.

In a 1997 monograph, the author and researcher Gary Schwindler recalled that Hawkins “never stopped collecting” all kinds of materials that could be turned into works of art “even when he didn’t need to.” (See Schwindler’s int, “You Want to See Somethin’ Pretty?,” in Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco, eds., William Hawkins Paintings (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), page ix.)

Log Cabin, c. 1986, oil enamel on Masonite, 35 ins. x 57 ins.

The artist told Schwindler: “You’re steppin’ over money if you don’t pick them up….I’m nothing but a junk man.” In fact, as critical recognition of Hawkins’ richly expressive painting style and inventive ideas has grown since his work’s first-ever public showing in an exhibition at the Ohio State Fair in 1982, so, too, has appreciation among art lovers in the U.S. and abroad of the energy and enthusiasm—call it magic—with which Hawkins turned his funky finds into enduring emblems of an unbridled creative spirit.

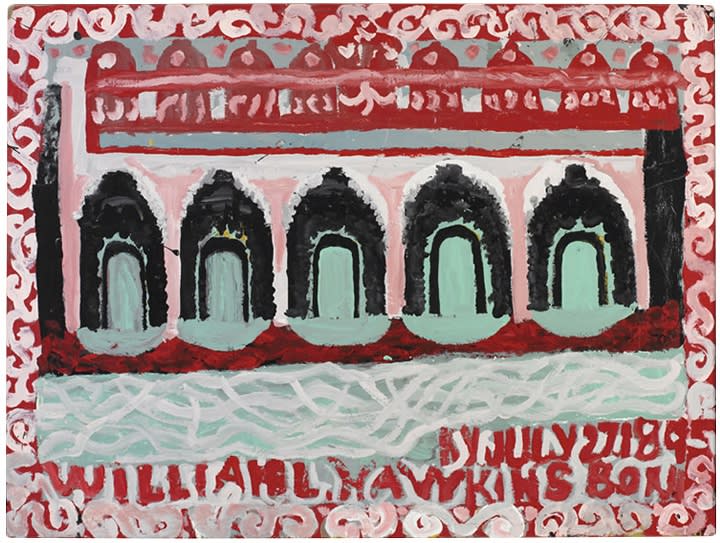

Historical Monument, c. 1986, oil enamel on Masonite

As the big block letters with which he inscribed his name and often identified his subject matter, right across the bottoms or the sides of his paintings, routinely indicate, Hawkins was born in eastern Kentucky on July 27, 1895. He was known to have been proud of his mixed white, black and Native American ancestry. Brought up on a farm by his maternal grandparents, he became skilled at caring for animals, constructing and repairing fences, and operating special tools and equipment. Once, during his teenage years, after hitching a team of horses to a plow as an ominous-looking storm rolled in, Hawkins was struck by lightning as it bounced off a nearby fence. He survived that near-death experience, an alarming encounter with the forces of nature that convinced the youth that the life that lay before him would be a special one.

Ohio Statehouse No. 2, c. 1985, oil enamel on Masonite, 39 1/2 ins. x 48 ins.

By the time he was 21 years old, Hawkins had fathered a child, but at the insistence of a shotgun-toting aunt, he left the infant and its mother behind and in 1916 headed to Columbus to begin what would become a long life as an urban jack-of-all-trades. Ultimately, he would also become an inventive artist whose distinctive style would earn the praise of critics, curators, collectors and other artists around the U.S. and overseas.

Hawkins began making art in the 1930s. For someone who had grown up on a farm, where he had learned to hunt and trap small animals, care for livestock and breed horses, animals were among the first subjects he depicted. Hawkins’ renderings of dogs, dinosaurs and buffalo are among the most indelible images in all of his multi-themed oeuvre; so, too, are his pictures of various architectural subjects, including the Alamo, the construction of the Statue of Liberty and assorted banks and hotels.

Jordan Memorial Temple, c. 1986, oil enamel on Masonite, 35 ins. x 57 ins.

Hawkins often used bright colors in audacious combinations that recall the exuberance of 1960s-era pop art or even the outrageous palettes of German expressionism, with their hints of psychological tension or high-pitched emotion. Whether dominated by single, large, space-filling subjects or packed with numerous figures, collaged elements and decorative patterns, including those that serve as borders to frame each image, Hawkins’ compositions often feel animated and convey a sense of real or imagined stories unfolding. (In fact, those who knew the artist well have recalled that Hawkins was always an entertaining storyteller.)

From January 7 through February 20, 2010, Ricco/Maresca, the exclusive representative of the Estate of William Hawkins, is presenting “William Hawkins: Architectural Paintings.” The exhibition features a selection of emblematic images of buildings and monuments whose vivid blends of bold colors, geometric shapes and brushy pattern-making have earned Hawkins’ paintings, which he usually made with enamel on board, the admiration of outsider art aficionados and contemporary-art collectors alike. Paintings on view in the exhibition depict such subjects as Ohio’s Statehouse, in Columbus, which Hawkins had seen many times in person, as well as the British Houses of Parliament, in London, and Hearst Castle’s Neptune Pool. The British-government buildings and that luxurious section of the 20th-century, American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst’s vast estate in California (which is now a state historic site) are subjects the artist would have known only from photos in magazines.

William Hawkins, with an automobile he decorated himself, at his home in Columbus, Ohio, in the early 1980s. (Photo: Roger Ricco)

In fact, Ricco/Maresca co-director Frank Maresca recalls, “Hawkins, who was always scavenging through the trash, used to clip photos of subjects that interested him from magazines. He would carefully fold his clippings and store them in a special suitcase that he would dip into for inspiration when thinking about what to paint. Just like many academically trained artists, in his own way, Hawkins was methodical and disciplined about doing the research that informed his art.”

Hawkins once observed about his work as an artist: “I don’t copy what I see. I make it better.” (See Joanne Cubbs and Eugene W. Metcalf, “William Hawkins and the Art of Astonishment,” Folk Art, fall 1997, page 60.) In recent years, as critical attention has focused more and more on the various technical and thematic affinities the works of self-taught artists may share with those of their formally trained modern and contemporary counterparts, Hawkins’ art has earned praise for its audacious use of color and the strong sense of design that is evident in its inventive compositions.

Now, with “William Hawkins: Architectural Paintings,” admirers of this definitive, American self-taught artist’s work will have an opportunity to examine in detail Hawkins’ distinctive representations of what, for him, appeared to have been iconic symbols of the built, urban environment that for much of his life had both challenged and intrigued this former Kentucky farmboy.