METROPOLITAN PAVILION

125 W 18TH ST

BOOTH A11

Ricco/Maresca Gallery has been participating in the Outsider Art Fair for 30 years now. Since the beginning, the fair has been filled with excitement, wonder, and the promise of an amazing future. That future is here. The field of Outsider and Self-Taught art has finally begun to receive the international recognition that it has always deserved. This year, we will be presenting an overview of classic works and new discoveries. Below you will find a complete digital presentation of our booth, along with narration by Frank Maresca. We look forward to seeing you at the fair and at our Winter Party on Friday, March 4 (6-8:30pm)—which will take place at our new expanded gallery space. Same building, same floor.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FAIR, CLICK HERE

-

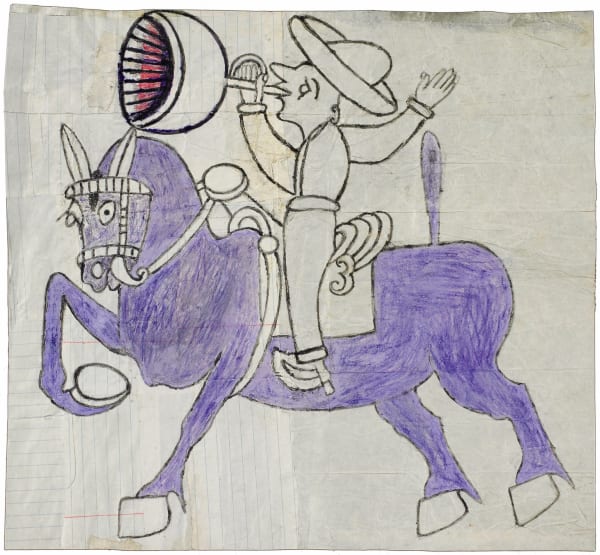

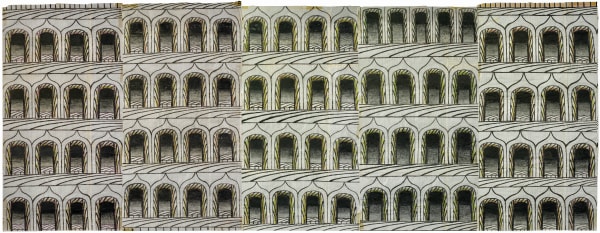

MARTÍN RAMÍREZ (1895-1963)

-

Untitled (Horse and Rider Hunting Rabbit), ca. 1960-63Gouache and graphite on pieced paper23.5 x 23 in. (59.7 x 58.4 cm.)(MR 052)SOLD

Untitled (Horse and Rider Hunting Rabbit), ca. 1960-63Gouache and graphite on pieced paper23.5 x 23 in. (59.7 x 58.4 cm.)(MR 052)SOLD -

Untitled (Abstraction with Arches), ca. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 018)$90,000

Untitled (Abstraction with Arches), ca. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 018)$90,000 -

Untitled (Horse and Rider with Bugle), ca. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper13 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (34.3 x 36.8 cm.)(MR 122)SOLD

Untitled (Horse and Rider with Bugle), ca. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper13 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (34.3 x 36.8 cm.)(MR 122)SOLD -

Untitled (Interior with Four Figures), ca. 1950-55Graphite, tempera, and crayon on paper17 1/2 x 24 in. (44.5 x 61 cm.)(NU 161.306)$110,000

Untitled (Interior with Four Figures), ca. 1950-55Graphite, tempera, and crayon on paper17 1/2 x 24 in. (44.5 x 61 cm.)(NU 161.306)$110,000

-

-

Born in Jalisco, Mexico, Martín Ramírez is widely known as one of the preeminent self-taught masters of the 20th century. Thrust by political and religious upheavals caused by the Mexican Revolution and seeking to support his family, Ramírez relocated to the United States in 1925. He worked as an impoverished immigrant in the California mines and railroads until he was picked up by police in 1931—reportedly in a disoriented state. Ramírez was eventually declared schizophrenic (with previous diagnoses of manic-depression and catatonic dementia praecox). He was committed first at Stockton State Hospital and then at the DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, where he spent the rest of his life. It was there where he discovered art and created the complex and compelling drawings and collages for which he is known.

Over the course of his life, Ramírez produced some 500 works characteristic for their clean yet brazen draftsmanship. The imagery is both suggestive and nostalgic, often reminiscent of his own life experiences. Mexican Madonnas, animals, cowboys, trains, and landscapes merge with scenes of American culture and create a profound documentation of a Mexican living and working in the United States. Compositionally, he renders space into multi-dimensional almost theatrical layouts using sharp geometric forms with strong linear qualities. He framed his drawings with sweeping lines that bring attention to centralized forms. The artist worked primarily in crayon and had a firm grasp of perspective and mark-making techniques consisting of rhythmic repetition and gentle shading. Later in his life, he began creating collage-type works, adding newspaper clippings and previous drawings for depth and texture.

Ramírez’s technical skill, stylistic evolution, and thematic coherence led Roberta Smith of the New York Times to call him “simply one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.” Early on, Ramírez’s talents were recognized in small exhibitions as early as the 1950s. Today his work has been the subject of numerous museum shows, including the retrospective “Martín Ramírez: Pintor Mexicano,” at the Centro Cultural/Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City (1989), and two major exhibitions at the American Folk Art Museum, NYC: a traveling retrospective titled “Martín Ramírez” (2007) and “Martín Ramírez: The Last Works” (2009). In 2010, the 20th century master was the subject of a comprehensive exhibition curated by Brooke Davis Anderson at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reína Sofía in Madrid, titled “Martín Ramírez: Reframing Confinement.” In 2015, the United States Postal Service released a set of 5 commemorative “Martin Ramirez” Forever stamps, which marked the first time an Outsider artist and Mexican-American artist was featured on a USPS Stamp.

Ricco/Maresca Gallery has represented the Estate of Martín Ramírez exclusively since 2008.

-

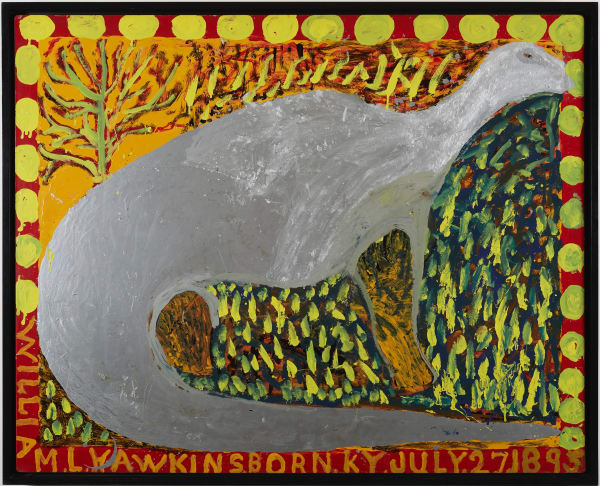

WILLIAM HAWKINS (1895-1990)

-

William Hawkins lived most of his life in Columbus, Ohio, after leaving there in his twenties to avoid a shotgun wedding. He was born in rural Kentucky and his early years on a farm afforded him a knowledge and love of animals—an awareness that informs many of his paintings. In Columbus he held an assortment of unskilled jobs and did not begin painting until the late 1970s. He worked without letup thereafter, in spite of illness and advancing age.

At first, Hawkins painted on plywood and discarded wall paneling with enamel housepaint in primary colors—which he salvaged from a local hardware store. Later, he worked on Masonite, which he preferred because he liked the way the paint "set up" on the surface. He painted with a single brush, whose bristles were almost down to the ferrule, wipping off each new color with an old rag. "I don't need but one brush," he would say. Hawkins poured and dripped paint—often directly from the can—letting it flow across the surface as he tilted it. Once, when Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco were watching him work, he looked up and said: "See dat, boys? the paintin's makin' itself."

Hawkins’s main source of inspiration was the print media of his time, the pictures in newspapers and magazines that he collected in a suitcase. His bold range of subject matter included animals (common, exotic, extinct, and semi-fantastical), cityscapes (iconic landmarks, depictions of prominent buildings), and classic religious and pop iconography. He often utilized collaged elements (such as eyes) and found objects, wood, sand, and sawdust to add texture to a painting, or "puff it out." His treatment of color and sense of composition were fearless, expressive, and improvisational, resulting in works that palpitate with their creator’s drive and imagination.

Hawkins would most often paint decorative borders around his work and include his name and birthplace in big handwriting—a signature element that was both visual and informational, and particularly symbolic given that the artist could scarcely read or write. The artist was proud of his age and wanted everyone to know it.

Hawkins did not receive recognition for his work until his friend Lee Garrett entered one of his paintings in the Ohio State Fair, where it won first prize. The artist was then in his eighties but continued to be immensely prolific. By the next year (1983), Ricco/Maresca Gallery had started representing him, launching his career nationally and internationally. In 1989 he suffered a stroke from which he only partly recovered and died months later, in 1990. Today, Hawkins’s work can be found in the permanent collections of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the American Folk Art Museum (New York), The Newark Museum of Art (New Jersey), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), the Columbus Museum of Art (Ohio), The New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington D.C.), among others. In 2018, William L. Hawkins: An Imaginative Geography, a comprehensive exhibition including 60 of the artist’s most important works and an accompanying catalog, opened at the Columbus Museum of Art—later traveling to the Mingei International Museum (San Diego, California), the Figge Art Museum (Davenport, Iowa), and the Columbus Museum in Georgia.

-

THORNTON DIAL (1928-2016)

-

Dial (1928 - 2016) was born in Emelle, Alabama. He grew up in poverty and received almost no schooling. Dial worked for the Pullman Standard Company for 30 years doing iron and cement work and only dedicated himself exclusively to art come age 55, when he was laid off from his job. In the three decades that followed he produced a vast oeuvre depicting the poignant complexities of African American experience.

The artist’s works on paper offer powerful insights into his psyche and vision; their fluidity and immediacy counterbalance the dense baroque qualities of his three-dimensional works. Dial completed each drawing quickly, capturing pictorial ideas while still crisp. This expressionistic drive materializes in sinuous lines, disjointed shapes, and forceful pigment stains. The drawings seen here show recurrent motifs in Dial’s oeuvre: women as eroticism personified (malleable creatures often anthropomorphizing fish and birds) and the interactions between men and women—sometimes dark and restless, other times bright and ecstatic. -

HENRY DARGER (1892-1973)

-

For most of his life, Henry Darger was employed as a janitor in Catholic hospitals. Come night, he gave expression to a private, aggressively original imaginary world—working from his small rented room in Chicago’s North Side. Over a period of more than 50 years, Darger created a magnum opus consisting of a 15,000-page illustrated saga titled “The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion” (commonly referred to as “In the Realms of the Unreal”). The 13-volume manuscript is reenacted in more than 300 watercolors and collages depicting the adventures of seven innocent heroines, the Vivian Girls, as they lead the rebellion against the evil, child-enslaving, adult Glandelinians.

Darger’s landscapes set the ambience for his tales of good versus evil; they are at once romantic, poetic, and often violent. The artist meticulously configured his compositions using tracings from the newspaper clippings and magazine illustrations he collected. He paid particular attention to visual space and perspective, utilizing a copy machine to size his figures relative to their placement within the picture plane. The artist’s extraordinary talent as a colorist and his dynamic compositions combine to create a formal beauty that renders even brutal imagery sublime. Some of his works evoke scenes of Civil War-torn battlefields—which he reputedly studied—complete with blustering winds, sleeting rain, and turbulent clouds (the artist kept a daily weather journal for 10 years). The Vivian girls engage in violent battles against the evil Glandelinian Army, they brave tornadoes and blazing forests, are strangled by clouds in the sky, and even “disappear through the earth” in miraculous escapes. Other works are bucolic, featuring imaginary places with fairytale-like names such as “Finger Mountain,” “Peppermint Place,” “Onion City” and “Mistletoe Station,” set within Darger’s Catholic land of Angelina.

Darger is perhaps the most well-known self-taught American artist; his works held in numerous museum and private collections in the United States and abroad. He has been the subject of major museum exhibitions and retrospectives, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York (1997 and 2010), Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago (2003), and The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo (2007), among others. In June 2012, Kiyoko Lerner (holder of Darger’s estate) donated 13 double-sided Darger drawings to the MoMA in honor of Klaus Biesenbach, who curated “Disasters of War” at MoMA PS1 (2000), which presented works by Darger alongside those of Goya and Jake and Dinos Chapman.

-

BILL TRAYLOR (1854 - 1949)

-

Although emancipated as a boy, Bill Traylor continued to labor until 1908 on a neighboring plantation in Benton, Alabama—near where he was born into slavery.

By 1910 he was a tenant farmer near Montgomery and it was only when he was in his eighties, and no longer able to do physical work, that he started making art with materials that lay to hand, learning to write his name so he could sign his work. From 1939 to 1942, Traylor produced more than 1,200 drawings that are of crucial significance in American art and social history.

Traylor’s imagery consists of laborers with hammers, drinkers with flasks, hunters with shotguns, dandies in hats, seniors with canes, rural pedestrians, and some anthropomorphic figures often overlooked. People quarrel and point, live poultry flap wings, and frightening dogs go on the attack; characters hide beneath or stand atop and stumble off structures; there is a lot of apparent pursuit and escape. His simplified, modern figures, especially in works he referred to as “exciting events,” seem not to be straightforward depictions of what he may have seen but, rather, projections from the heart of his experience, distilled by memory.

Traylor’s posthumous recognition has expanded steadily ever since his death in 1949, and today his work is in important private and museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), and the Smithsonian Museum (Washington D.C.). -

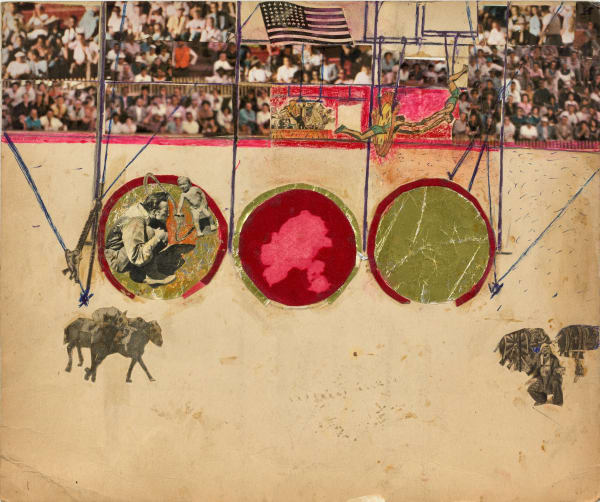

C.T. MCCLUSKY (UNKNOWN DATES)

-

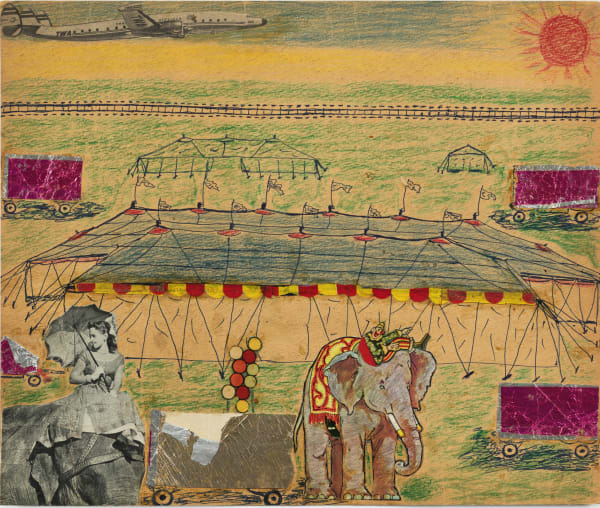

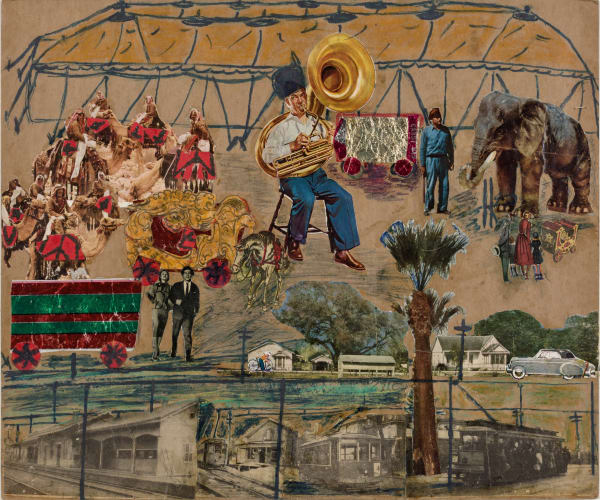

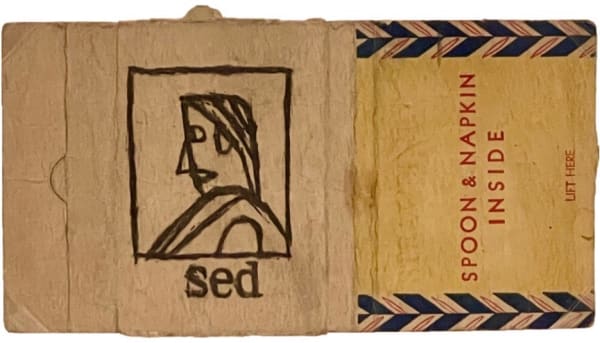

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 9)$8,000

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 9)$8,000 -

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 5)SOLD

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 5)SOLD -

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 8)$8,000

Untitled, ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)(CTMC 8)$8,000 -

Untitled , ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard

Untitled , ca. late 1940s-1950sMixed media with collage on cardboard13 x 15 1/2 in. (33 x 39.4 cm.)

(CTMC 21)$8,000

-

-

The only known beginning of C. T. McClusky’s story dates back to a Sunday morning in 1975 when a middle-aged woman named Corine set up a booth at the Penny Flea Market Island Drive in Alameda, California. A battered old suitcase glued to a large, worn-out paper cutout of the word CIRCUS stood there silently shouting out its name amid the bric-à-brac, and it caught the attention of John Turner—then a volunteer curator at the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco. With just one brief look at the suitcase’s contents, he realized he had “stumbled upon a treasure.” It was relayed to Turner that McClusky was a circus clown who lived during the winter seasons between the late 1940s and mid 1950s in an Oakland boarding house run by Corine’s mother. He kept few personal belongings there other than a stack of Life magazines and newspapers; he occupied his time off the road creating mixed-media collages that resurrected the circus in its absence and on occasion, Corine recalled, would present a work to her or one of her playmates.

If McClusky was born around the turn from the 19th to the 20th century, as a youth he was right in the middle of the second Industrial Revolution’s avalanche of new technology following the first transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. New inventions included the telegraph, the phonograph, the incandescent lightbulb, telephone, radio, motion pictures, automobiles, aircrafts, and television. The rise of mass marketing and consumer culture in postwar America brought a proliferation of imagery of this new world across print media. McClusky appropriated and repurposed pieces of this graphic excess into his mental geography—materializing again and again in his collages—and in doing so he found a formal and spiritual outlet that paralleled Surrealism’s best efforts to free the unconscious mind from creative restraints. McClusky’s collage milieux engage in all manner of interesting visual discrepancies: photography converges with caricature; black-and-white with Technicolor; naturalism with hyperbole; perspective and proportion are thoroughly out of synch. As John Turner points out,* the artist subscribes to a kind of hieratic visual logic, indicating importance by size and not necessarily by placement—so we see a cheetah that could match King Kong, or a ringmaster towering over the big top, almost audibly summoning us with his trumpet.

Adding to this representational pastiche, the artist’s circus landscapes include a junction of signifiers from different settings and time periods. The crowd around the big top includes fashionable people dressed in business or casual attire, men in factory-work clothing, suburban families and urban loners, mounted cowboys in hats and neckerchiefs, Plains Indians in feathered headdress. McClusky’s fixation with modes of transportation mirrors that of a collector: passenger and freight trains (steam engines, diesel, and electric locomotives), airplanes, automobiles, trucks, buses, trolleys, trailers, motorcycles; even prairie schooners make an appearance around his circus. His particular insistence on trains and airplanes suggests a sense of connectivity—to an expanse outside the picture—but also estrangement and dislocation, especially when they travel at unstable or illogical angles.

-

Eddie Arning (1898-1993)

-

Eddie Arning grew up on his father's farm in Germania, Texas-about 50 miles northwest of Houston. His bouts of depression and anger eventually culminated in an attack against his strict Lutheran mother. He was briefly hospitalized following the incident. After being committed to a mental institution for the second time in 1934, he was diagnosed with so-called dementia praecox (more commonly schizophrenia) and remained in treatment for 30 years.

Like many other self-taught artists, Arning was introduced to art by a member of the helping professions. In 1964, a teacher employed by the hospital offered him wax crayons, paper, and coloring books. Their flat restricted forms seem to have shaped his visual sensibility, but his ability to master more complex arrangements of figures, colors, and patterns grew rapidly-as did his repertoire of materials and images. Arning's early works appear to have been autobiographical, but he later took inspiration from newspaper stories, magazine photos, advertisements and other material from pop culture. He eventually began to work in oil pastels, which lent a soft, glowing, almost floating quality to his shapes.

After he was released from the hospital, Arning spent his final decade in a nursing home, where he turned his room into a studio and continued to work. He produced nearly a drawing per day, and gained a significant local reputation. In 1973, however, he was asked to leave the nursing home because of his refusal to abide by its rules. Arning then went to live with his widowed sister, but a long-established creative and physical equilibrium had been disturbed and he ceased drawing altogether. "That's hard work," the aged artist once remarked. Arning's work is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Milwaukee Art Museum, and the American Folk Art Museum in New York, among others.

-

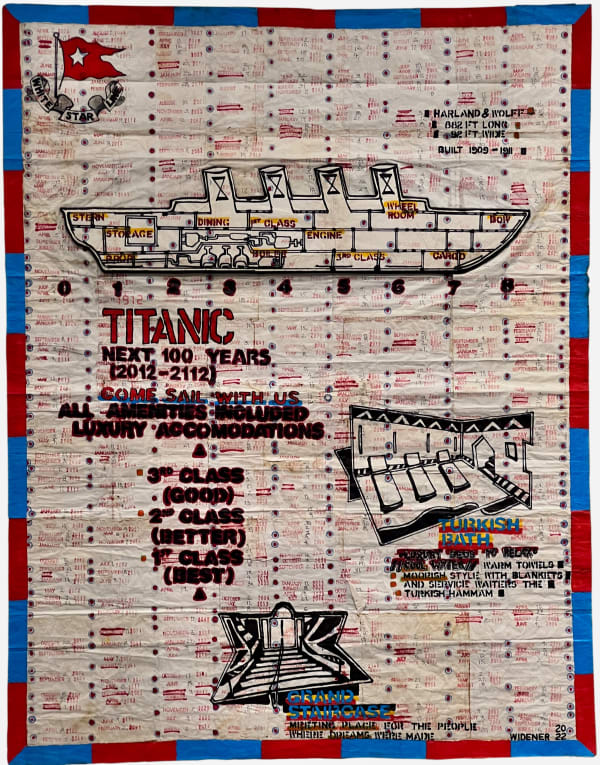

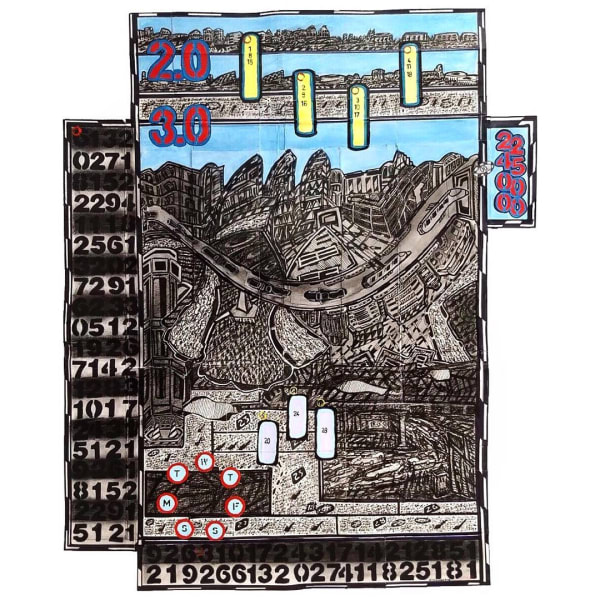

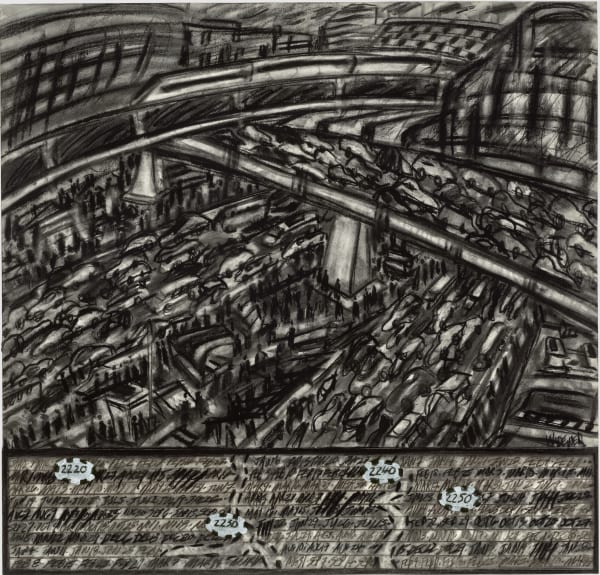

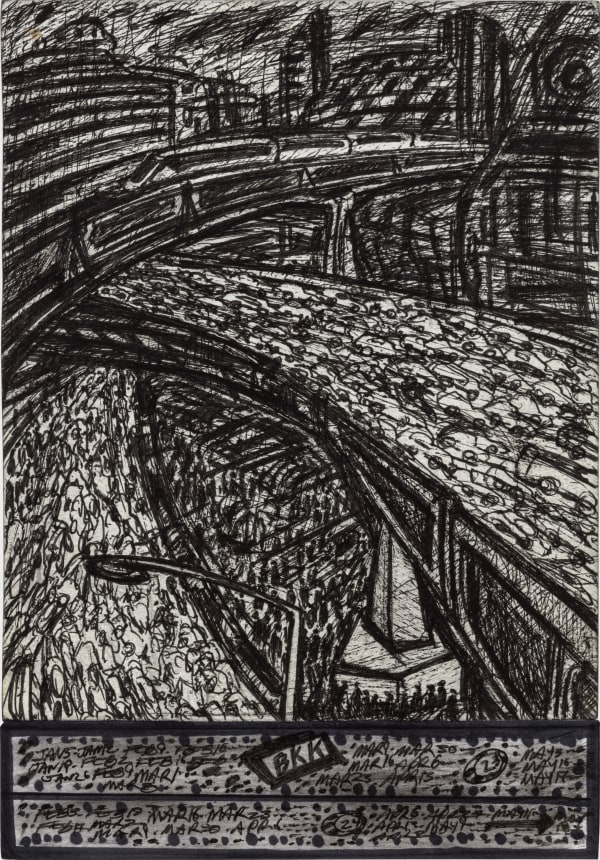

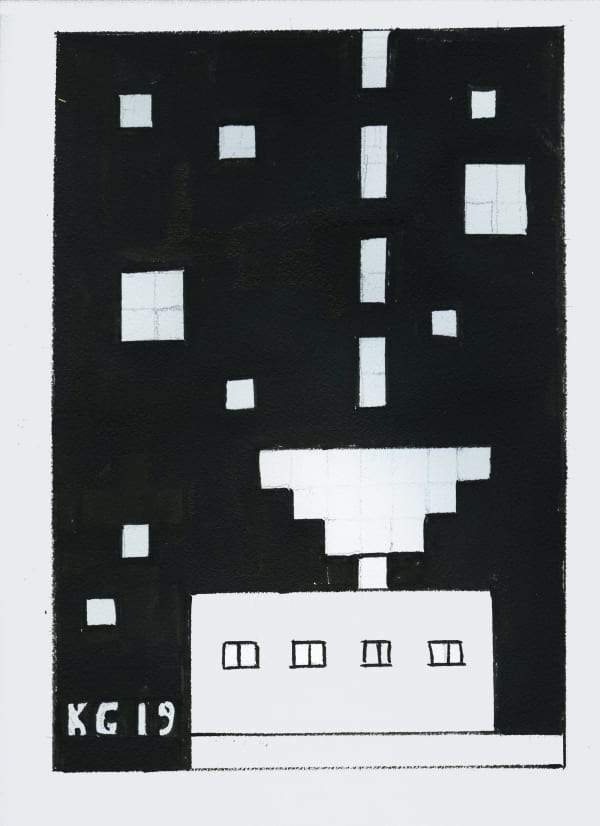

GEORGE WIDENER (B. 1962)

-

-

Untitled (Bangkok Cityscape), 2017Ink and charcoal on paper9 3/4 x 12 in. (24.8 x 30.5 cm.)(GW 220)SOLD

Untitled (Bangkok Cityscape), 2017Ink and charcoal on paper9 3/4 x 12 in. (24.8 x 30.5 cm.)(GW 220)SOLD -

Untitled (Cityscape), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper8 x 18 1/2 in. (20.3 x 47 cm.)(GW 228)SOLD

Untitled (Cityscape), 2020Ink and charcoal on paper8 x 18 1/2 in. (20.3 x 47 cm.)(GW 228)SOLD -

Untitled (Bangkok Landscape), 2018Ink and charcoal on paper10 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. (26.7 x 18.4 cm..)(GW 223)$3,000

Untitled (Bangkok Landscape), 2018Ink and charcoal on paper10 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. (26.7 x 18.4 cm..)(GW 223)$3,000

-

-

Widener, who sometimes likens himself to a “time traveler,” has been highly visible in the contemporary art arena and has had significant film and media exposure. On October, 2012, Nova Science aired “How Smart Can We Get?” featuring a segment on Widener. He was also profiled in “Ingenious Minds: George Widener,” the last episode of a six-part series of films focusing on savants and geniuses—which aired on the Discovery Science Channel in March, 2011. The artist is also a subject in the 2007 documentary film “My Brilliant Brain: Accidental Genius.”

Widener’s work has been extensively exhibited worldwide. The artist was part of the exhibition “World Transformers: The Art of the Outsiders,” at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Germany (2010) and “Exhibition 1” at the Museum of Everything in London, UK (2009). Additionally, 14 of Widener’s works were in the exhibition “Hiding Places: Memory in the Arts” at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, WI (2011). Widener was also included in the exhibition “The Alternative Guide to the Universe,” curated by Ralph Rugoff at The Hayward Gallery in London (2013).

Widener’s work is in private and museum collections worldwide, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum in Berlin, the Museum Gugging in Klosterneuburg, Austria, the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands, the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the abcd/ ART BRUT collection and the Centre Pompidou, both in Paris.

-

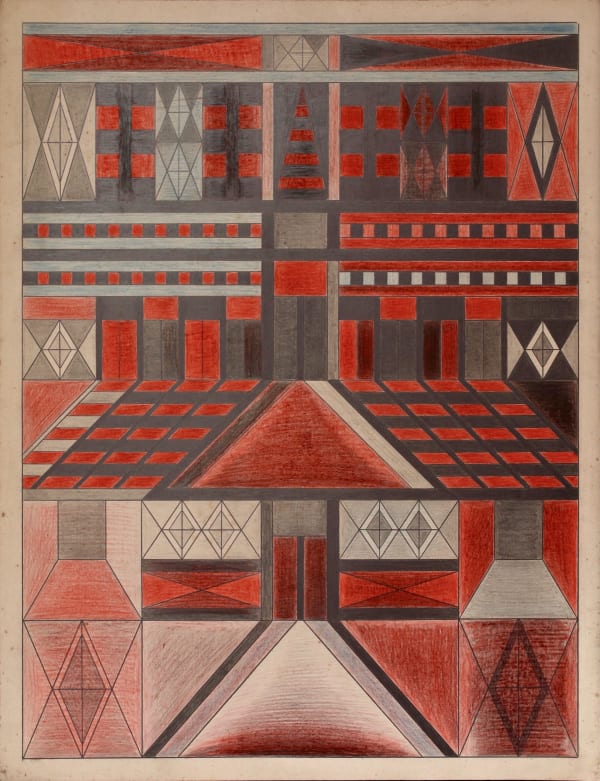

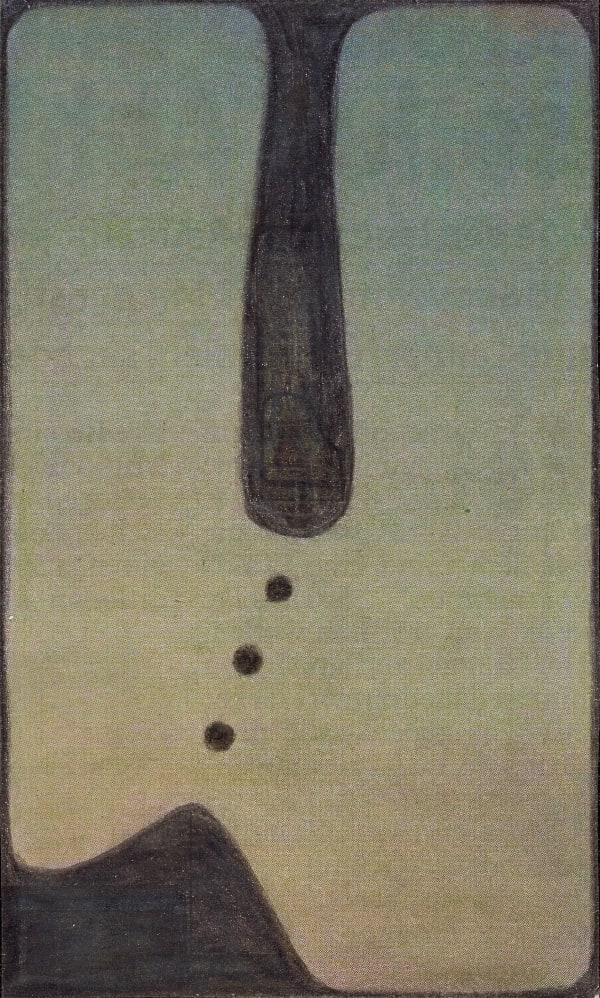

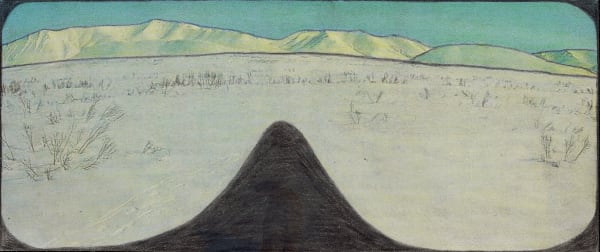

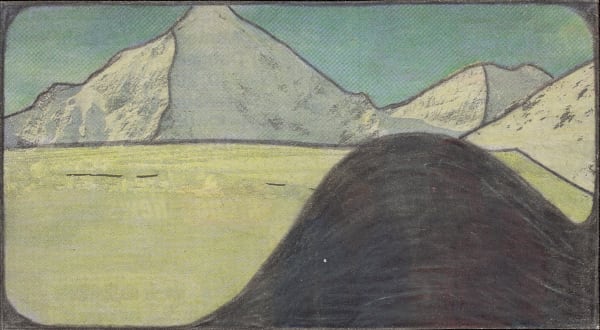

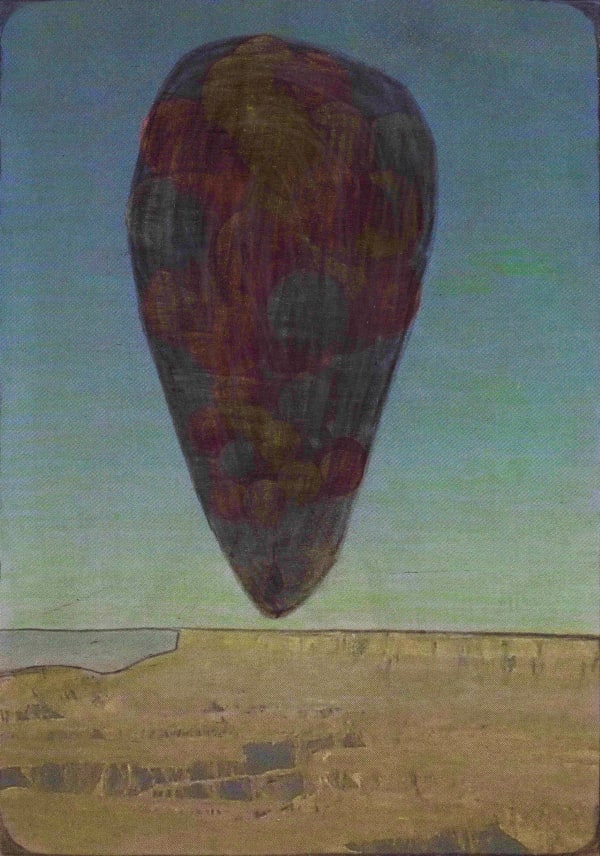

DOMINGO GUCCIONE (1898-1966)

-

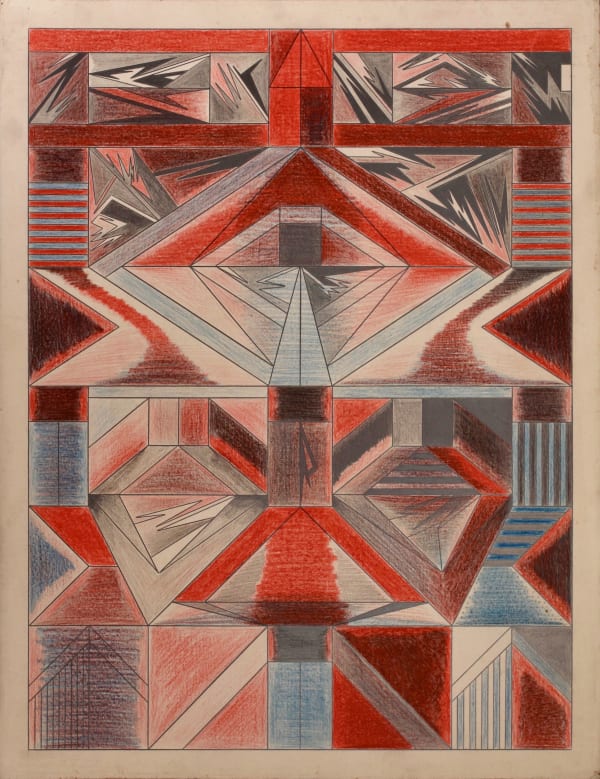

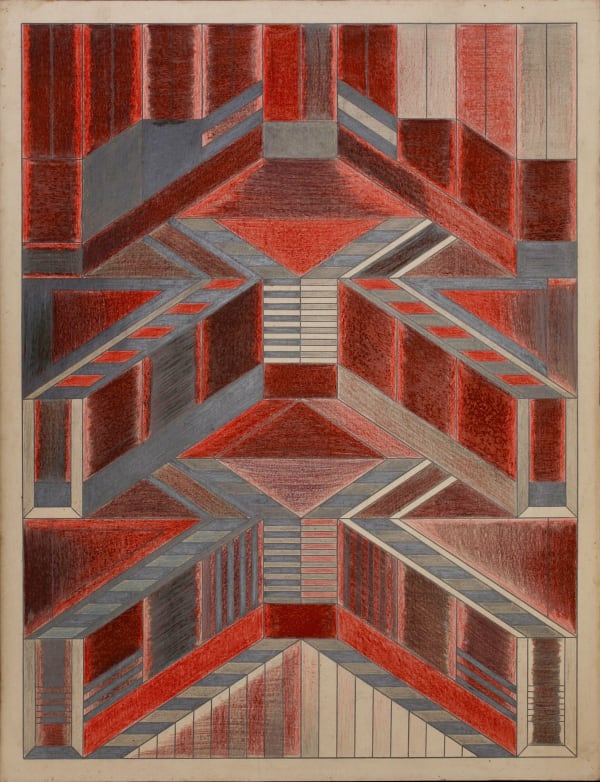

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 24)$8,000

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 24)$8,000 -

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 32)$8,000

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 32)$8,000 -

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 30)$8,000

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 30)$8,000 -

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 6)$8,000

Untitled, ca. 1930-55Colored pencil and graphite on paper25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm.)(DG 6)$8,000

-

-

Domingo Guccione (1898 – 1966) was born in Buenos Aires to Italian parents. He was a trained classical musician, working as a concert guitarist and instructor to many students, but was never exposed to visual art—and in fact suffered from color blindness. He drew mostly in private and claimed to be channeling a mysterious force that took a hold of him in bouts of creative energy—where his body and mind were not his own. Accordingly, Guccione could (or would) not explain his finished works and in turn ask viewers what they saw in them.

Guccione did not sketch his drawings, working quickly and with a minimal range of materials; thick sheets of paper, graphite, colored pencils, and a straight piece of wood, about 4” long, with no measurement markings. The 222 works that he left behind, which were produced between 1930 and 1955 and have never been seen outside of his immediate family, are compact kaleidoscopic arrangements where geometric patterns intertwine with irregular linear shapes. They are both deeply abstract and reminiscent of futuristic architectural landscapes; of buildings and labyrinths that fluctuate between flatness and three-dimensionality, interweaving densely packed color with subtle shadings

-

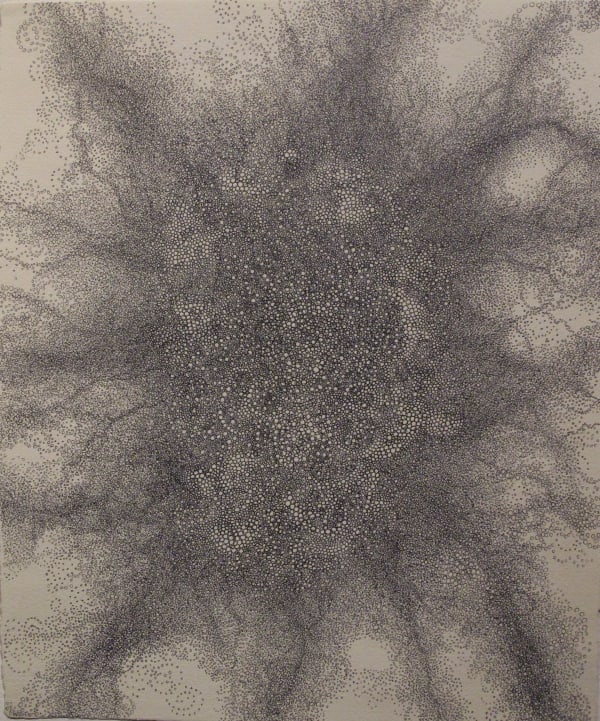

HIROYUKI DOI (B. 1946)

-

Hiroyuki Doi was born in Nagoya, Japan. He began his career in 1980, after the death of his younger brother. This life-changing trauma redirected his energies to the creation of visual art, soon eclipsing his training as a chef. “I started to feel that something other than myself allowed me to draw these works.” His very personal rationale for pursuing an artistic career meant that it was many years before he began to show his work at public exhibitions in Japan. It was not until 2001 that Doi’s work was first seen in the West, at the Phyllis Kind Gallery in New York. Thereafter, he has attracted considerable critical attention.

Doi combines the traditions of Asian and Western art, referring back to the Sino-Japanese tradition of ink painting (zhe/dunjinga) that became popular from the Edo period onward. He is aware of the Outsider and Self-Taught traditions in the West, as well as the art pioneered in Japan by Atsuko Tanaka and other artists of the post-war gutai movement. The artist follows in direct, linear descent from the great draftsmen of Japan’s past: Nagasawa Rosetsu, Katsushika Hokusai and many others. Using an archival Japanese ink pen, he creates meticulous works made of tiny circles that grow organically to become complex compositions, embodying a spiritual preoccupation with the relationship between the smallest part and the whole; from cellular biology to the cosmos. “His drawings are at once microscopic while paradoxically appearing to contain the infinite vastness of the universe, or a star-filled sky,” wrote Lindsay Pollock in Art in America (2011).

-

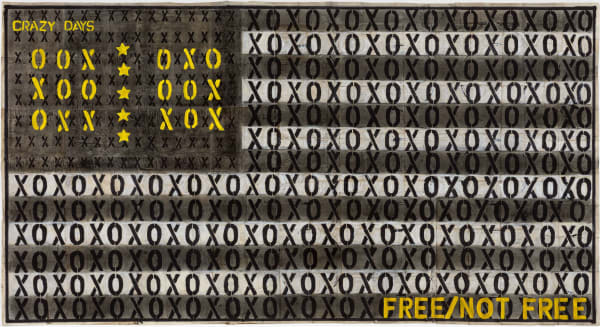

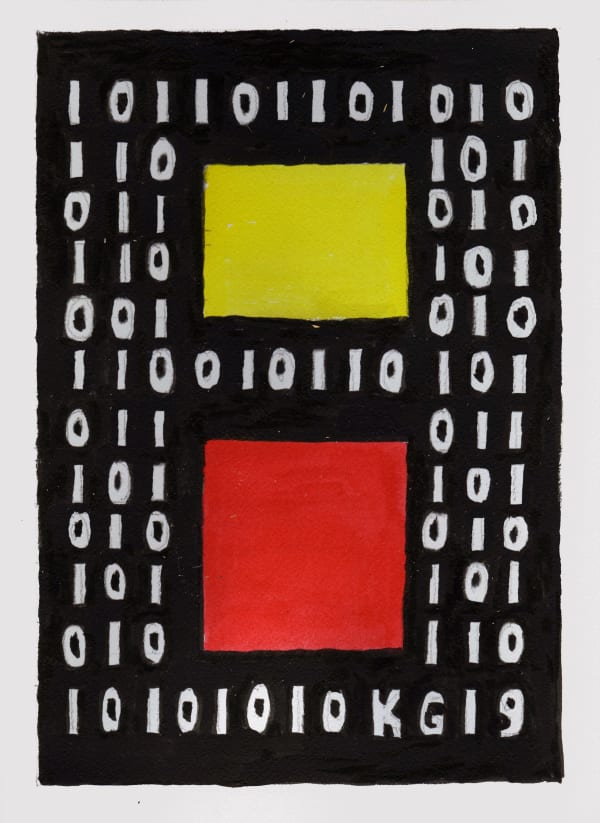

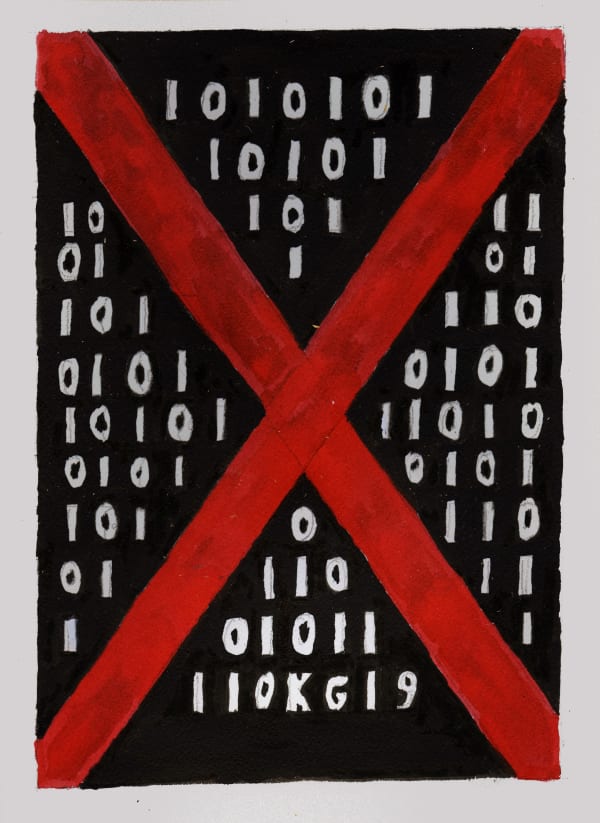

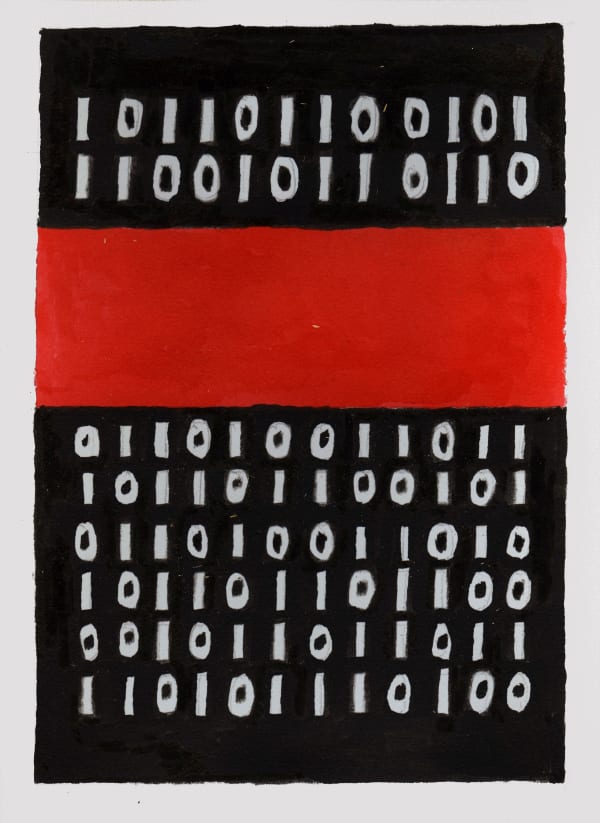

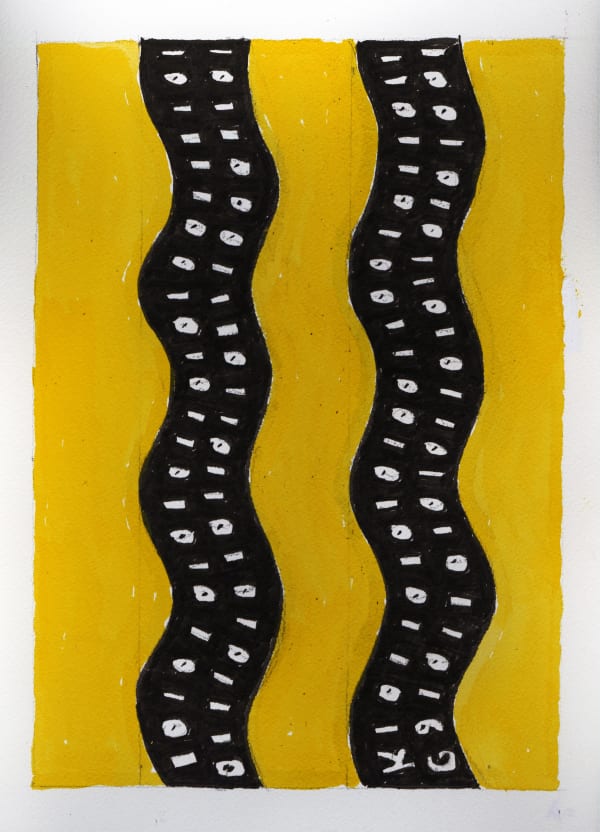

KEN GRIMES (B. 1947)

All works: Ink on paper. 12 1/4 x 9 in. (31.1 x 22.9 cm.) | $2,200 ea. -

Ken Grimes was born in New York City and grew up in Cheshire, Connecticut. For more than 40 years, he has diligently maintained a stark palette of black and white, which he believes is the most direct way of showing the contrast between truth and deception. Only recently, he ventured into a new series of works that incorporate basic colors to the same end. The artist’s paintings and works on paper, which oscillate between whimsical and stern—but are often both—are conceptual, never-ending variations on the themes of extraterrestrial intelligence and cosmic coincidence; a window to a world where aliens, flying saucers, UFOs, crop circles, radio telescopes and interstellar signals are an essential part of reality. Grimes’s artistic project strives to prompt viewers into thinking about the existence of aliens and the importance of making contact with them.

The artist's work is in the permanent collections of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and the American Folk Art Museum. In 2018, his work was selected as one of the exhibitions in a six-part yearly series titled “Field Station” at Michigan State University’s Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum. In 2019, he was invited to participate in the deCordova Museum Biennial. Anthology Editions is currently in the process of developing a volume on Grimes's life and work.

-

GÜNTHER SCHÜTZENHÖFER B. 1965

-

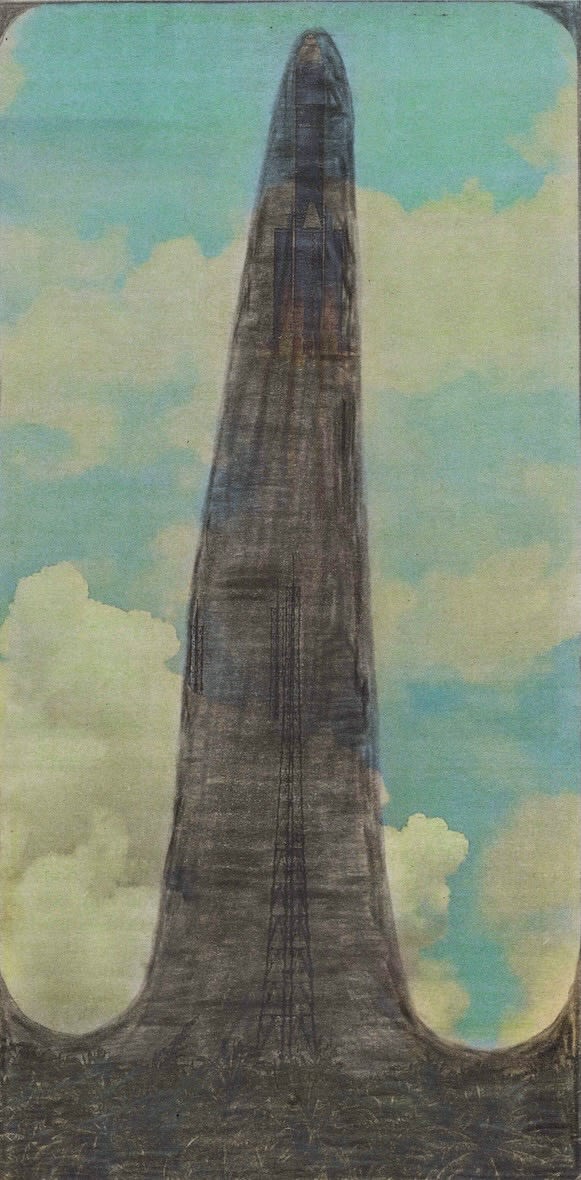

Sunshade, 2019Graphite on paper27.5 x 19.8 in. (70 x 50 cm.)(GSG 116)$8,000

Sunshade, 2019Graphite on paper27.5 x 19.8 in. (70 x 50 cm.)(GSG 116)$8,000 -

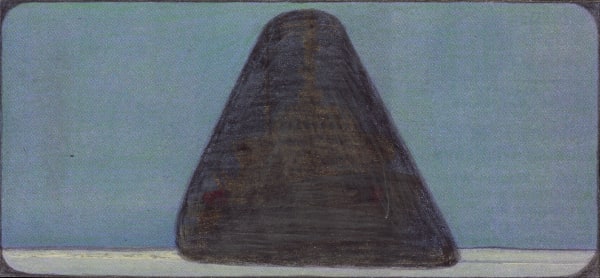

Butterfly, 2017Graphite on paper16.5 x 23.4 in. (42 x 59.5 cm.)(GSG 110)$7,000

Butterfly, 2017Graphite on paper16.5 x 23.4 in. (42 x 59.5 cm.)(GSG 110)$7,000 -

Trumpet, 2016Graphite on paper19.7 x 27.5 in. (24.6 x 10.8 cm.)(GSG 118)$8,000

Trumpet, 2016Graphite on paper19.7 x 27.5 in. (24.6 x 10.8 cm.)(GSG 118)$8,000 -

Bottle, 2019Graphite on paper27.6 x 19.7 x in. (70.1 x 50 cm.)(GSG 120)$8,000

Bottle, 2019Graphite on paper27.6 x 19.7 x in. (70.1 x 50 cm.)(GSG 120)$8,000

-

-

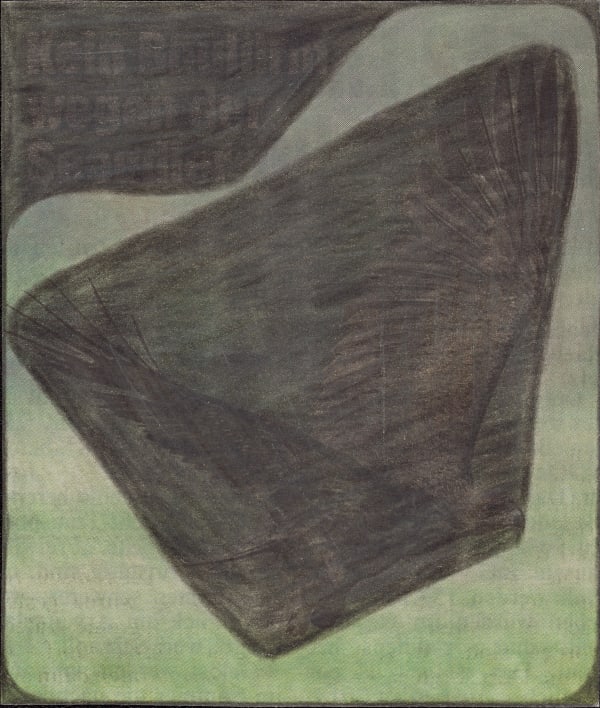

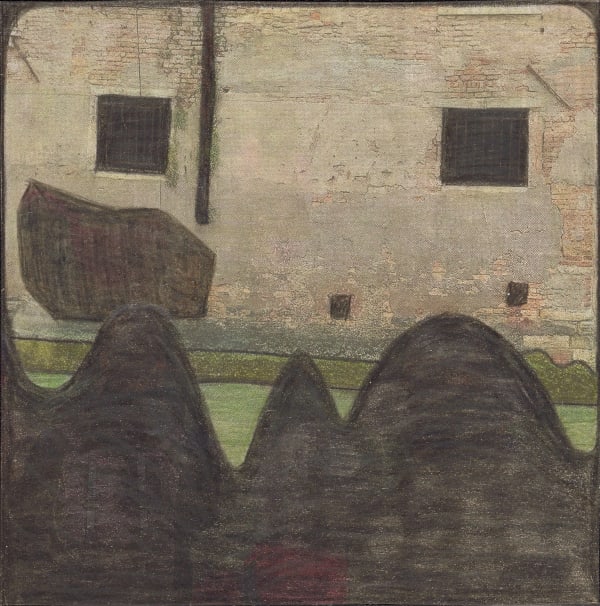

Günther Schützenhöfer was born in Mödling, Austria. As a six-year-old, he arrived at the former Gugging Clinic and spent his life in various care facilities until 1999, when aged 34, he moved into the Gugging House of Artists, where he produced his first drawings. Over the past 15 years, Schützenhöfer has developed a unique, unmistakable style. He portrays elements from his surroundings in an abstracted, self-contained manner, which is joyfully unconcerned with perspective; nearly enigmatic yet always permeated by the artist’s subtle humor.

At first, Schützenhöfer worked very cautiously and mostly in small formats. Over time, the formats have grown larger; fine lines giving way to bold, determined strokes. He works in pencil and colored pencils on paper and cardboard. He sketches out his theme in a few lines, then uses stronger pressure with his pencil to bring it to life. Sometimes this pressure will break the pencil; for this reason, the artist keeps at least five sharpened pencils readily available, and once he has used them all, he will grab any other pencils lying around on the table. This constant change in pencils of different grades and the varying touch he applies, results in idiosyncratic shadings and a soft, almost furry texture.

Schützenhöfer chooses his themes spontaneously, often related to the current season or situation. His approach is entirely focused on the essence, the gist of his theme. Limiting himself to the vital elements, he produces drawings and compositions that are unique in their overall sophistication. Schützenhöfer’s works have been shown worldwide since 2001 and are represented in numerous private and public collections, such as the Lower Austria Regional Collection, the Museum of Everything, the Peter Infeld Private Trust, and the Arnulf Rainer Collection.

-

Leopold Strobl (b. 1960)

-

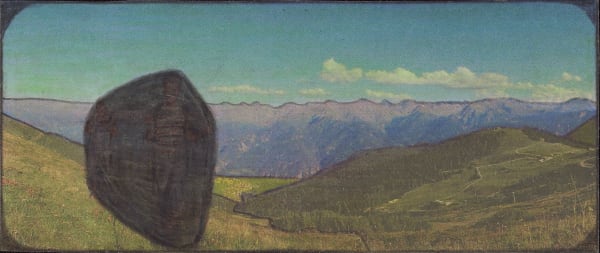

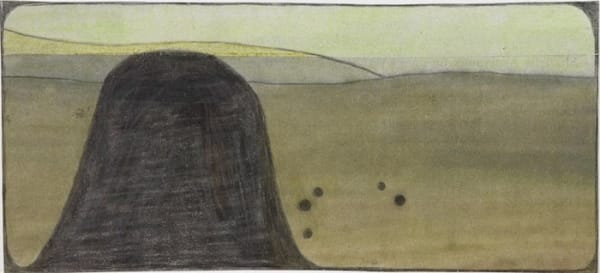

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2 1/2 x 5 7/8 in. (6.3 x 15 cm.)(LpS 301)SOLD

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2 1/2 x 5 7/8 in. (6.3 x 15 cm.)(LpS 301)SOLD -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper7 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (19.1 x 9.5 cm.)(LpS 375)SOLD

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper7 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (19.1 x 9.5 cm.)(LpS 375)SOLD -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.7 x 5.9 in. (6.8 x 14.9 cm)(LpS 351)SOLD

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.7 x 5.9 in. (6.8 x 14.9 cm)(LpS 351)SOLD -

Untitled, 2016Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.5 x 5.6 in. (6.5 x 14.4 cm)(LpS 287)SOLD

Untitled, 2016Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.5 x 5.6 in. (6.5 x 14.4 cm)(LpS 287)SOLD

-

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip and mounted on paper4.4 x 2.6 in. (11.3 x 6.7 cm)(LpS 366)$2,900

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip and mounted on paper4.4 x 2.6 in. (11.3 x 6.7 cm)(LpS 366)$2,900 -

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper3.3 x 7.7 in. (8.3 x 19.6 cm)(LpS 342)$4,300

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper3.3 x 7.7 in. (8.3 x 19.6 cm)(LpS 342)$4,300 -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.1 x 3.8 in. (5.3 x 9.6 cm.)(LpS 336)$2,500

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.1 x 3.8 in. (5.3 x 9.6 cm.)(LpS 336)$2,500 -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper5 3/8 x 3 3/4 in. (13.7 x 9.6 cm.)(LpS 376)SOLD

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper5 3/8 x 3 3/4 in. (13.7 x 9.6 cm.)(LpS 376)SOLD

-

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.8 x 4.1 in. (7.2 x 10.4 cm)(LpS 373)SOLD

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.8 x 4.1 in. (7.2 x 10.4 cm)(LpS 373)SOLD -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper3 1/8 x 4 3/4 in. (7.7 x 11.9 cm.)(LpS 377)$2,900

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper3 1/8 x 4 3/4 in. (7.7 x 11.9 cm.)(LpS 377)$2,900 -

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper4.3 x 3.6 in. (10.9 x 9.1 cm)(LpS 370)$3,200

Untitled, 2020Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper4.3 x 3.6 in. (10.9 x 9.1 cm)(LpS 370)$3,200 -

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.6 x 4.1 in. (6.6 x 10.4 cm)(LpS 326)SOLD

Untitled, 2019Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint clip mounted on paper2.6 x 4.1 in. (6.6 x 10.4 cm)(LpS 326)SOLD

-

-

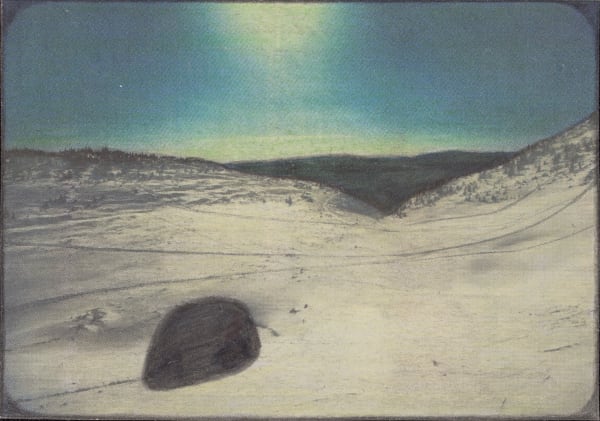

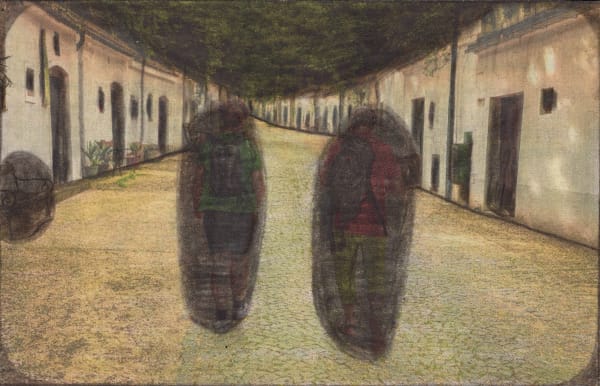

Strobl was born in Mistelbach, Lower Austria. He has devoted himself exclusively to art for almost 40 years, and has been a guest of the Open Studio program at the Gugging Art Brut center in the outskirts of Vienna for more than 16 years. He draws in the morning and single-mindedly finishes a new piece per session. This impetus is significant both in terms of form and content: the artist's works are generally no bigger than 8 ½ inches on the longest side and can be almost as small as a postage stamp; they come to the artist as little visual epiphanies and strike the viewer with this poetic immediacy.

Strobl's process is a seamless, multilayered appropriation and alteration of a photographic base. It starts with combing through the local newspapers for evocative images that will lend themselves to the transformation that is to come. Strobl then scissors these images out of their original context and backs them with clean drawing paper. We know the steps that follow and the simple materials utilized (graphite and colored pencils), but not in what order, or if there is one—as the artist doesn't speak of it or allow onlookers when he is working. Strobl's compositions are generally encased in a drawn internal frame that is either very subtle (delicately enclosing each scene with rounded corners) or partially amorphous, covering large areas like a spill or a flood. Depending on the disposition of the underlying clip, he traces over certain outlines—topographic features, horizon lines, architectural details, winding perspectival lines--and if there are figurative elements that don't fit into the artist's vision, he encloses them in graphite, like an insect spinning a cocoon, or a minimalist reducing a representational image into a basic shape.

-

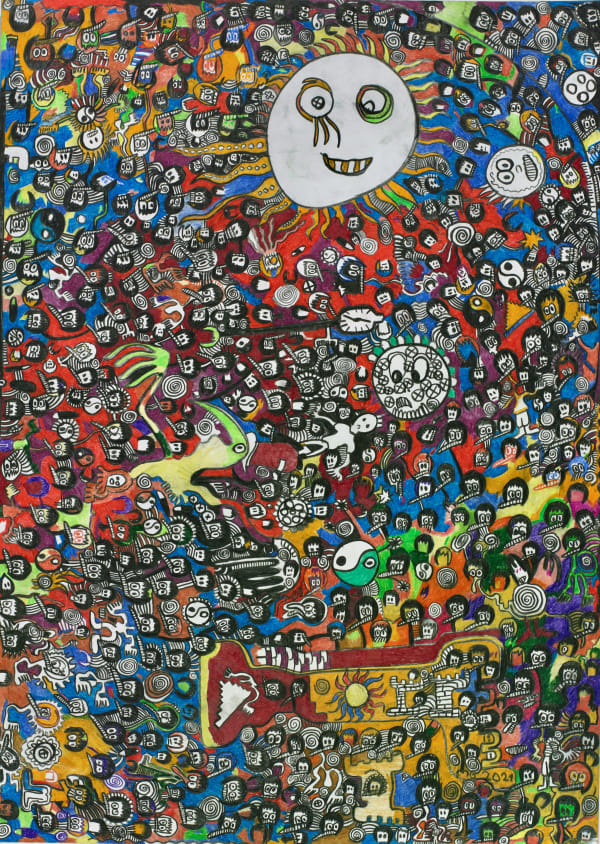

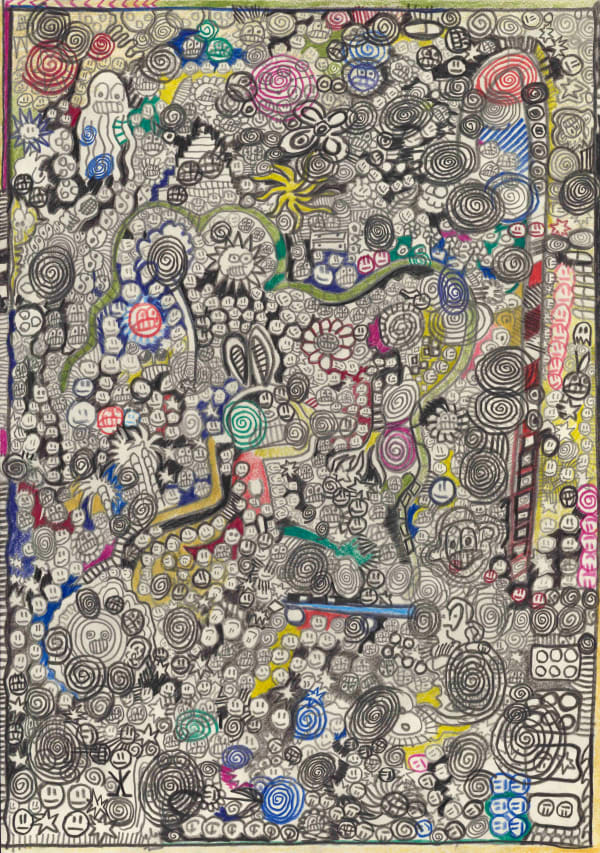

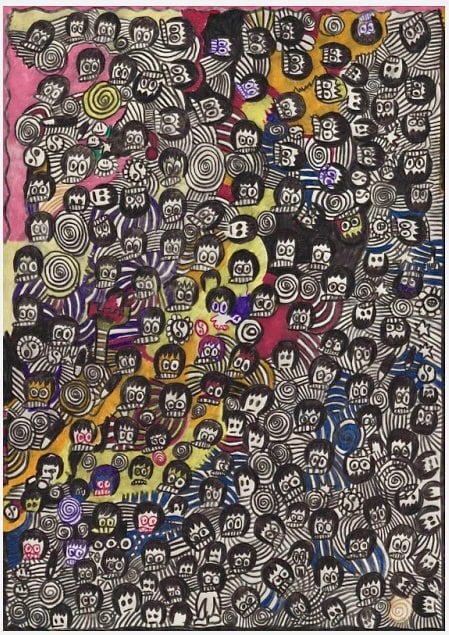

Manuel Griebler was born in Kirchdorf, Austria. Since 2016 he has lived in the Gugging House of Artists in the outskirts of Vienna—which is part of Gugging, Europe’s premier center for the creation and presentation of “art brut.”

Griebler works with colored pencils on paper. He usually begins by drawing a central figure to mark and anchor the beginning of the composition, then he develops the remaining pictorial space with ornamental and recurring elements—spirals, arches, figures, circles, jags. Since 2020 heads are a dominant theme in Griebler’s work. -

MANUEL GRIEBLER (B. 1991)

-

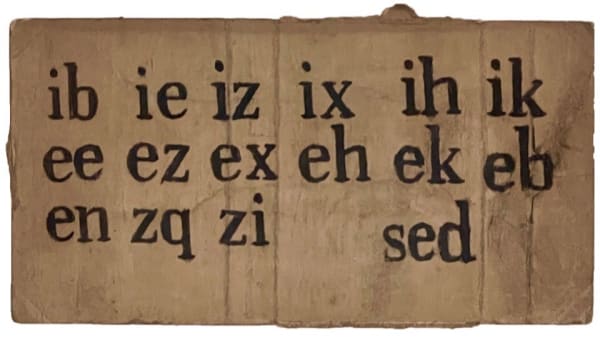

James Castle (1899–1977)

-

James Castle was born profoundly deaf in the mountainous town of Garden Valley, Idaho. Perhaps owing to his disability, Castle, the fifth of seven children, did not attend school before the age of ten, but spent most of his time at home, drawing and crafting objects from a very young age.

He devoted his long, secluded life to creating an immense opus that comprises drawings, paintings, assemblages, sculptural objects, text pieces, and artist’s books. Although he knew little about the world beyond his narrowly circumscribed community and nothing about art history, today his work is regarded as parallel to vanguard art of the twentieth century.

Castle worked entirely with found materials; his daily rummage of trash cans provided an abundant supply of discarded paper, printed media, and empty containers. He used soot that he gathered from a wood-burning stove and mixed with his own saliva as his main pigment, which he applied with matchsticks, fountain pen tips, and even apricot pits rather than brushes.

Castle’s work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New York Public Library, the American Folk Art Museum (New York), the Berkeley Art Museum, the Boise Art Museum, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Tacoma Art Museum, and the Milwaukee Art Museum. -

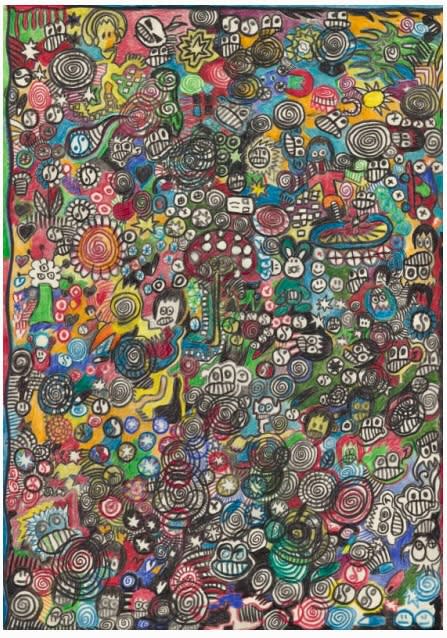

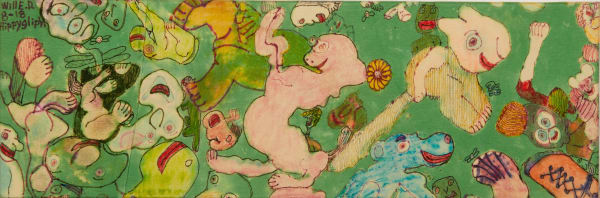

William E. Doleman (B. 1949)

-

William Eugene Doleman is seriously invested in herbology, alternative medicine, and a concept of spirituality where humans and their environment are intrinsically connected.

When he moved to California in the early 1990s Doleman started to tie-dye fabrics, and at one point it occurred to him to cut and stretch them to utilize as canvases. This pre-existing color base serves as inspiration for the drawings that emerge: whirlpools of figures with varying degrees of human and animal traits that coexist happily in a flexible non-perspectival space—which Doleman manipulates by removing some of the color (or un-dying) to create negative spaces, luminosity, and contrast.

The artist describes his process as meditative; a kind of “no-mind’ state where he is able to communicate with good spirits and create his own version of the Garden of Eden; a place of absolute harmony; beaming with intoxicating colors and uncontainable joie de vivre. “In my works, figures are in crowded conditions, but nobody is scowling at each other, they’re all smiling because they’re happy to be there, it’s an acceptance that I think all people need to have, with each other and the environment,” he says. The word “Hippygliph” is often floating within these compositions, as Doleman thinks of his works as hieroglyphs of his generation.

-

American Unidentified

-

Carnival Clown Shooting Target Details