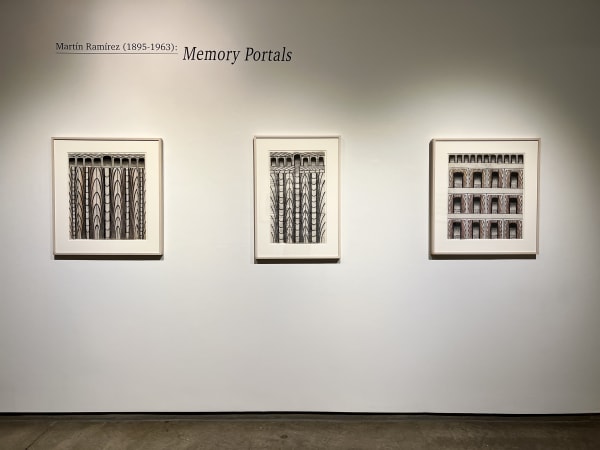

Martín Ramírez: Memory Portals

A prolific draftsman and collagist, Martín Ramírez (1895-1963) is considered one of the preeminent self-taught masters of the twentieth century. From ranch owner and agriculturist in Mexico, to miner and railroad worker in the United States, to patient and artist at two psychiatric hospitals in California—only in recent decades have we been able to appreciate the full complexity of Ramírez’s life. A quintessentially twentieth century life that provided the source material for his sophisticated and enchanting compositions. Despite the hurdles Ramírez faced in his life—the economic instability following the Mexican Revolution, his migration to the United States, his self-imposed exile during the Cristero Rebellion, economic precarity during the Great Depression, and forced institutionalization in U.S. psychiatric hospitals—Ramírez was able to insist on creativity. He began to make drawings as early as 1935 during the formative years of arts and crafts therapy in the United States. In these early years, the products of arts therapy were not valued as objects and were often discarded. It is a wonder, then, that his artwork survived and even more so that it continues to circulate in the art world of the twenty-first century.

This conversation with Brooke Davis Anderson, one of many figures responsible for the stewardship of Ramírez’s artistic legacy, demonstrates the importance of care in facilitating the ongoing recognition of this industrious, resourceful, and imaginative artist.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

***

Juan Omar Rodriguez: Can you tell me about how you came across Ramírez’s work?

Brooke Davis Anderson: It would have been circa 1983. I was in college and was already deeply committed to what we called at the time “contemporary folk artists,” and today would call “self-taught artists.” Back in the mid-nineteen eighties, there were few publications, but one by Herbert Hemphill, entitled Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists (1974), included Ramírez. Aligned with the narrative of that time, it positioned the artist as someone who was “deaf, mute, and schizophrenic.” This is a myth.

In the 1990s there was a wave of exhibitions, publications, curators, collectors, and fairs that really changed the landscape for self-taught artists. Around this time a sociologist from Mexico, from Jalisco—the same region that Ramírez is from—Victor Espinosa, saw an exhibition of Ramírez’s work in Mexico City and fell deeply in love with it. But he was frustrated by the presentation, its lack of scholarship. And aren’t we lucky that he got so incensed? Victor decided to find out everything he could about Ramírez. Victor worked with his former wife, Kristin Espinosa. The two of them devoted all their free time to Ramírez research. This resulted in extraordinary and exciting new knowledge. They were even able to locate and befriend Ramírez’s family.

Victor is such an important architect of Ramírez’s legacy. I was taken by Victor and Kristin’s scholarship, so I collaborated with them on an exhibition of Ramírez’s work in 2007 at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, with the goal of presenting a new framework for Ramírez and his art.

JOR: These assumptions about Ramírez were in the works for decades, and as a curator you were probably trained to privilege a certain idea of what “fine art” is, who “fine artists” are, and would have been encouraged to continue this mythologizing of Ramírez. How did you come to take self-taught artists seriously? How were you able to embrace the possibility that interpretations of Ramírez’s work and life weren’t accurate?

BDA: There were some skeptics about Victor’s research and his findings, but I championed it from the beginning. Gratefully, there was unconditional support at the American Folk Art Museum. The museum staff believed that Victor’s research needed to be heard, even though clearly there were a lot of people who were beholden to an antiquated understanding of Ramírez.

In many ways Ramírez’s story is the farthest thing from being exotic and outsider-y. It is a quintessential American narrative: the tale of hundreds of thousands of people. It is about caretaking, of crossing borders, and of survival. I wish we could acknowledge how un-sensational it is; he was like so many migrants who are leaving, moving, hoping to get work and care for their family.

If we could look at his work as a journal, we might see his production with more clarity. The artist shares his life story, his travels, his passions, his motivations, his heartbreaks, his anger, his love, and his curiosity. When we start to look at the work in that way, then we get to see the ordinariness of Ramirez, of his all-too-human experience. Then what unfolds is how extraordinary his line and form really are. There’s no one who paints and draws like him. There’s no one who sets up the page like him.

JOR: Part of Ramírez’s legacy comes from his desire to provide for his family, and then also from the care that other people have extended to him throughout his life that allowed him and his legacy to survive. Conversations like ours and exhibitions of his work that present him as an artist and invite people to sit with his work are a form of care. This care helps us grapple with the nuances of Ramírez’s experiences—characterized by struggles, yes, but also by agency and creativity.

I appreciate the context that you’ve provided in this conversation. What where the aspects that struck you from his work?

BDA: It’s so sensitive for you to recognize the caretaking that he received, because that’s absolutely true. You know, he had patrons from the beginning of his thirty-year career as an artist. That’s a very exciting and a very important part of the story.

Just thinking about the ways in which he was resourceful and creative, how Ramírez made exhibitions and shared his work with audiences. It was exciting to learn that Ramírez actually displayed his artwork at DeWitt State Hospital. Whether it was Tarmo Pasto’s class from Sacramento State that Wayne Thiebaud attended, or others interested in the creative process, Ramírez came up with singular solutions (like cutting out the handle of a paper bag and using the handle) to hang his artwork on the walls.

He took pride in his work. He saw it as something of value. It was exciting to learn that it wasn’t enough for Ramírez to draw with a wax crayon but that he melted it so that he could paint with it.

JOR: A hundred or so of Ramírez’s drawings were found in 2007. How did this come about?

BDA: I placed news stories in local newspapers because I knew there had to be more Ramírez work near Auburn and Sacramento. When Peggy Dunievitz contacted the American Folk Art Museum about a suite of drawings stored in her garage, it was affirming and exciting. The Dunievitz family, who thought they had about fifty works of art and ended up having about a hundred-and-forty works of art, were one of several owners of Ramírez’s artworks that came forward after the 2007 exhibition. I believe there is still more work to be found, shared, and researched.

JOR: The development of this story—of Ramírez’s work and his legacy—is like a salve to the difficult history of Ramírez’s life and early interpretation. What are some of your hopes for this exhibition of Ramírez’s work at Ricco/Maresca Gallery?

BDA: I’m always hopeful that the Ramírez family is receiving recognition for the legacy that Ramírez has provided all of us.

I am optimistic that the political and social natures of the work are the next doors of scholarship needing to be opened. To further contextualize Ramírez’s art into that political, social, and cultural landscape is an essential next step.

I also hope that the people who are appreciating Ramírez, buying Ramírez, and marketing Ramírez support migrants, not only in the Americas but elsewhere, too, and understand that it is the movement of people that allows for deeply potent and poignant cultural encounters such as we get to have with the work by Martin Ramírez.

Brooke Davis Anderson is the inaugural Executive Director of VIA Art Fund in New York City and curator of the seminal exhibition Martín Ramírez at the American Folk Art Museum in 2007. She has published and lectured extensively on Ramírez and other artists who stubbornly exist on the false borders of the mainstream art world.

Juan Omar Rodriguez is a curator of contemporary art and is currently the Curatorial Fellow at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He foregrounds the agency of artists—contemporary and historical—in his research and writing.

-

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on pieced paper22 1/2 x 80 in. (57.1 x 203.2 cm.)(MR 078ABCD)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on pieced paper22 1/2 x 80 in. (57.1 x 203.2 cm.)(MR 078ABCD) -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Trains and Tunnels) A, B, c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper20 x 89 in (50.8 x 226.1 cm)(MR 098AB)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Trains and Tunnels) A, B, c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper20 x 89 in (50.8 x 226.1 cm)(MR 098AB) -

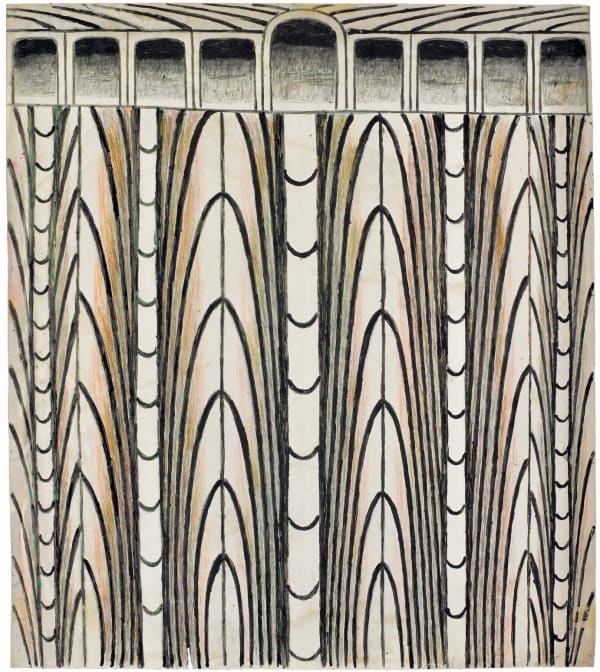

Martín Ramírez007 ABC, Untitled, (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper22.25 x 59 in. (56.5 x 149.9 cm.)

Martín Ramírez007 ABC, Untitled, (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper22.25 x 59 in. (56.5 x 149.9 cm.) -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches, 5 Panels), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on paper28.5 x 73 in. (72.4 x 185.4 cm.)(MR 065-069)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches, 5 Panels), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on paper28.5 x 73 in. (72.4 x 185.4 cm.)(MR 065-069)

-

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper15 1/2 x 34 1/2 in. (39.4 x 87.6 cm.)(MR 084)SOLD

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper15 1/2 x 34 1/2 in. (39.4 x 87.6 cm.)(MR 084)SOLD -

Martín Ramírez

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63

Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper16 x 22.5 in. (40.6 x 57.1 cm.)(MR 016)SOLD -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache and graphite on pieced paper16.5 x 21.5 in. (41.9 x 54.6 cm.)(MR 003)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache and graphite on pieced paper16.5 x 21.5 in. (41.9 x 54.6 cm.)(MR 003) -

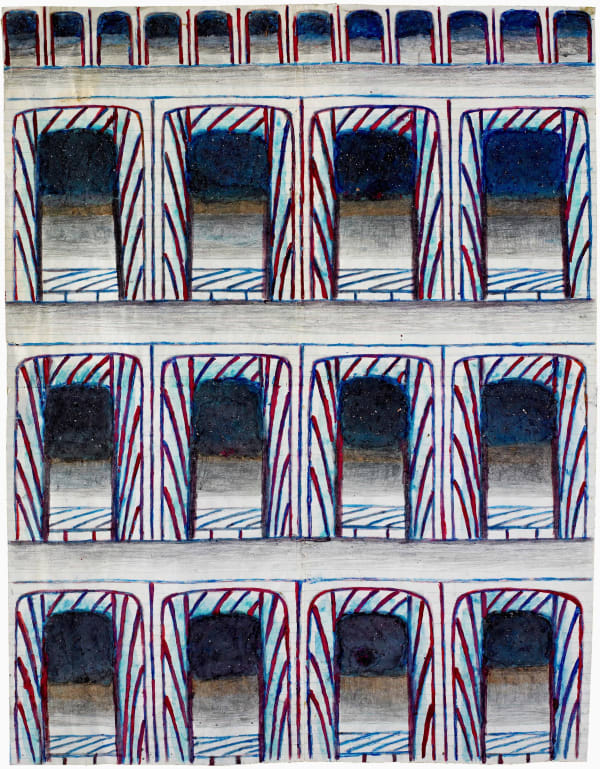

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper22 x 16.5 in. (55.9 x 41.9 cm.)(MR 001)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil and graphite on pieced paper22 x 16.5 in. (55.9 x 41.9 cm.)(MR 001)

-

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 071)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 071) -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Abstraction with Arches), c. 1960-63Graphite and gouache on pieced paper24 x 15 in. (61.0 x 38.1 cm.)(MR 116)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Abstraction with Arches), c. 1960-63Graphite and gouache on pieced paper24 x 15 in. (61.0 x 38.1 cm.)(MR 116) -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Abstraction with Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 018)

Martín RamírezUntitled (Abstraction with Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper22 1/2 x 20 in. (57.1 x 50.8 cm.)(MR 018) -

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, graphite on pieced paper21.5 x 16.5 in. (54.6 x 41.9 cm.)(MR 004)SOLD

Martín RamírezUntitled (Arches), c. 1960-63Gouache, colored pencil, graphite on pieced paper21.5 x 16.5 in. (54.6 x 41.9 cm.)(MR 004)SOLD